American Anthem: How Buffalo Springfield’s ‘For What It’s Worth’ Captured Youth In Revolt In 1967

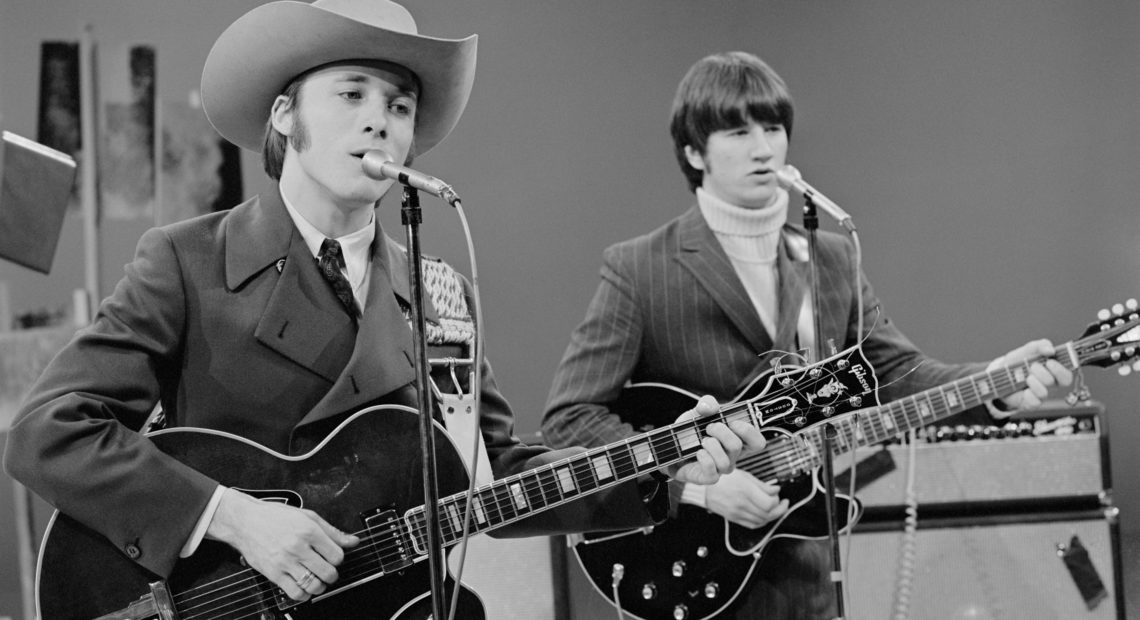

PHOTO: Stephen Stills (left) performs with Buffalo Springfield on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967. CREDIT: CBS Photo Archive/CBS via Getty Images

This story is part of American Anthem, a yearlong series on songs that rouse, unite, celebrate and call to action. Find more at NPR.org/Anthem.

LISTEN

BY DANNY HAJEK, NPR

It was February 1967, and 18-year-old Marine Pfc. Bill Ehrhart was days away from leaving for Vietnam. He had just enjoyed his last weekend off base, and his friends had offered to drive him back to Camp Pendleton, Calif., before sunrise.

“It was goodbye civilian world, next stop Vietnam,” says Ehrhart, now a writer and poet.

During their nighttime drive down the California coast, his friends turned on the radio — and that’s when Ehrhart first heard it:

The radio was playing “For What It’s Worth” by Buffalo Springfield, the folk-rock group led by Stephen Stills and Neil Young.

“I vividly remember thinking, ‘Wow, what a cool song,’ ” Ehrhart says. “By the time I left the country, the anti-war movement was still very much a fringe movement, so I literally didn’t understand what those guys were singing about.”

While it’s often recognized as an anti-war protest anthem, “For What It’s Worth” wasn’t actually based on Vietnam. Stills, who wrote the song, was instead inspired by a confrontation back home that erupted on a few famous blocks in Los Angeles.

LA’s Sunset Strip was a world away from Vietnam: a crowded boulevard lined with billboards, dumpy music clubs and a diner packed with teenagers. In the 1960s, the area held the pulse of rock and roll counterculture — and it’s where Buffalo Springfield made its name.

“It was like a carnival midway,” says music photographer Henry Diltz, who used to hang around the Strip. “Hundreds and hundreds of young kids, all dressed up in bell bottoms and tie-dyes, and they would come in and out of the clubs and walk up and down the street. It was kind of a happening.”

But behind the vibrant nightlife, there was simmering tension. Owners of upscale restaurants and fancy storefronts complained that the hordes of teens were bad for business. Meanwhile, Los Angeles County Supervisor Ernest E. Debs wanted to construct a new freeway and turn the Sunset Strip into a financial district, according to the book Riot on Sunset Strip: Rock ‘n’ Roll’s Last Stand in Hollywood.

In an effort to clear out what Debs called the “beatniks” and “wild-eyed kids,” LA County began enforcing a 10 p.m. curfew for anyone under 18. In response, the youth scene turned into waves of teenage-led protests against law enforcement.

“These were not friendly neighborhood cops in a blue uniform,” Diltz says. “These were patrolmen with helmets and great big jackboots and billy clubs. It was kind of a scary scene in the midst of all that peace and love.”

On Nov. 12, 1966, a crowd of young people gathered outside a club called Pandora’s Box to protest the “disrespect and abuse of youths by police,” as flyers distributed around the area described it. Hundreds of teens jammed the boulevard, some holding signs: “Rights For Youth Too,” “Stop Blue Fascism,” “Leave Us Alone.”

Police shouted back through bullhorns: “Anyone under the age of 18 years old remaining in the area will be arrested.” When demonstrators refused to leave at 10 p.m., the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and LAPD began their crackdown. The confrontation became known as the Sunset Strip Curfew Riots.

Protesters gather outside Pandora’s Box on Nov. 12, 1966. CREDIT: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

A local KBLA disc jockey who went by the name Humble Harve broke format to take calls from listeners about “the situation on the Sunset Strip.” “I’ve seen it,” one caller told him on-air. “I’ve seen the teenagers beaten — beaten — by the police.”

Michael Rummans, a local musician and Sunset Strip regular, says he still remembers how he was confronted the moment he pulled up to the scene: “A cop came up to me, and he said, ‘Get out of here right now or I’ll drag you out of that car and kick the s*** out of you.’ ”

“We decided not to leave,” says Francie Zbilski, who was inside Pandora’s Box with her boyfriend that night. “We were all kind of prepared for the idea that we were going to be arrested.” The club was usually a noisy scene with rowdy crowds and live music, but that night, she says, patrons were quiet. She could hear the commotion outside, and then came a loud bang on the door.

“I never saw so many policemen in my entire life,” she says. “We were just surrounded by police officers, like an army of them.”

Zbilski says she was marched outside so they could check IDs. “The cop behind me stuck a billy club in between my shoulder blades and gave me a good shove, which elicited me turning around and giving him the finger — because, you know, at 16 I was really brave,” she says, laughing. “I wouldn’t do that now.”

Down the street, protesters had taken over a city bus. As police rushed to intervene, Zbilski slipped into the crowd. She was never arrested.

As legend has it, Stills, disturbed by the images of police brutality from that night, wrote “For What It’s Worth” in 15 minutes. Band manager Richard “Dickie” Davis was in the studio when Buffalo Springfield recorded the song.

“It was recorded in one night: vocals, overdubs, bass track, all that was done in one night,” Davis says. For all that momentum, however, Stills was afraid of how the band might be typecast if the song did catch on.

“That name, ‘For What It’s Worth,’ is the most ‘aw, shucks’ kind of name,” Davis says. “Like, ‘Oh yeah, well, here’s my opinion, you don’t have to listen to it.’ … He was worried about it defining the group and he didn’t want that to happen.”

But it did: “For What It’s Worth” became an enduring hit. Whether one hears it as about the Vietnam War or the Sunset Strip, the song was for the young people caught on the front lines.

“The song was about the times,” Davis says. “The protests for the Vietnam War were in play right then, and they were on Stephen’s mind just as much as anything else. The song was written about the Sunset Strip, but it’s bigger than that.”

Thirteen months after he heard the song on his way back to base, Ehrhart returned from Vietnam. It wasn’t the war he had expected. “Within a few months of my arrival in Vietnam, I had realized, ‘I don’t know what’s happening here, but it sure as heck isn’t what Lyndon Johnson and my high school teachers told me was going on,’ ” he says.

As anti-war demonstrations grew across the country, Ehrhart’s politics gradually changed, too. The next time he heard Buffalo Springfield, “For What It’s Worth” meant something else.

There’s something happening here

What it is ain’t exactly clear

There’s a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware

“I realized, hearing that song again — ‘Oh, wait a minute. I was the guy with the gun over there. I’m the bad guy,’ ” Ehrhart says. “Every time I hear that song, I think about how innocent I was, how little I knew. I had no idea what was about to happen to me. And that’s what the song brings back for me.”