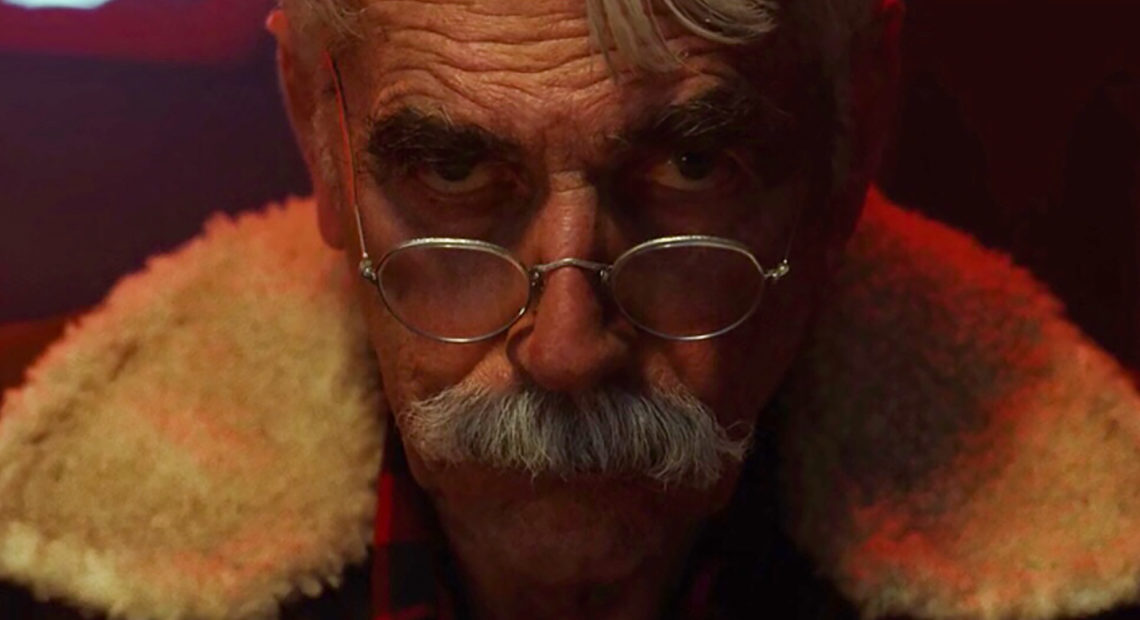

FILM REVIEW: Sam Elliott Is ‘The Man Who Killed Hitler And Then The Bigfoot’ — Or Is He?

PHOTO: In The Man Who Killed Hitler And Then The Bigfoot, Sam Elliott stars as an esteemed war veteran who helped kill Hitler. Years later, he’s on a new mission — to kill Bigfoot. CREDIT: Epic Pictures

BY SIMON ABRAMS

If you left A Star is Born: Take Four wanting more where co-star Sam Elliott’s scene-stealing performance came from, check out The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot.

No, seriously: The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot is a real movie — one more emotionally resonant and character-driven than that deceptively goony title suggests. The film — writer/producer Robert D. Krzykowski’s directorial feature debut — features a great lead performance from Elliott as Calvin Barr, a disillusioned World War II vet who struggles to remember that one time he killed Adolf Hitler.

Calvin is a great role for Elliott at this point in his storied career. Always a welcome and reliable screen presence, the actor’s singular gifts risk making him seem too idiosyncratic for a macho leading man (Mask, The Legacy) and too iconic for a Byronic character actor (Thank You for Smoking, Hulk). But recently, Elliott has handily played introspective guy’s guys in worthy films like the 2017 character study The Hero and the 2015 romantic comedy I’ll See You In My Dreams (both written and directed by Hearts Beat Loud director Brett Haley). Krzykowski’s drama also gives him plenty of opportunities to bring his stock mannerisms to bear: that enigmatic smirk, that mystifying stare, that avuncular grumble.

As Calvin, Elliott spends a lot of time asking other people — and himself — what they want from him. He struggles to articulate complex emotions, sometimes because he can’t remember what he wanted to say, and sometimes because several other characters patronize his character due to his advanced age.

Calvin doesn’t have many personal relationships (strong or otherwise), except for his golden retriever and his affable barber Ed (comedian Larry Miller). So it’s not surprising that Calvin glares his way through a visit from the FBI’s errand boy Flag Pin (Ron Livingston), who asks Elliott’s character to serve his country one last time by, uh, killing Bigfoot.

Calvin is the sort of tight-lipped guy who prefers to be alone with his memories, which are represented here through flashbacks. Unfortunately, most of these Lost-style flashbacks are uninvolving, partly because Aidan Turner (who plays a younger version of Calvin) isn’t as eye-catching as Elliott. But these flashbacks are also visually unremarkable, which is a significant problem, since three of the film’s seven(!) flashbacks concern the titular Nazi assassination plot. Krzykowski’s lack of story-telling experience shows most during these scenes.

Then again, Krzykowski does not appear to have consistently prioritized visual or narrative dynamism when he made The Man Who Killed Hitler And Then The Bigfoot. For better and worse, the film feels like the product of a busy, but unfocused imagination. Calvin may spend most of his time thinking about the past, but he doesn’t do much about his memories. Things just … happen to him, as when the FBI propositions Calvin only after more than 40 minutes have passed in the film’s sluggish 97-minute runtime. Worse still: Calvin’s flashbacks remind viewers that Krzykowski’s movie is not a linear, emotionally simple power fantasy. Elliott even spells out that theme when he tells Flag that Calvin’s heroic past was “nothing like the comic book you want it to be.”

Thankfully, Krzykowski and his collaborators nail several key scenes, like the flashback where Turner’s Calvin stammers as he asks his love interest Maxine (Caitlin FitzGerald) to marry him before he leaves home to serve in the army. It’s a tough scene to pull off: a complicated mix of romance, comedy, and tragedy. But the patience that Krzykowski applies to his characters’ dialogue — and the way he dotes on Fitzgerald and Turner’s faces by shooting them in warmly lit medium close-ups — gives this crucial moment sufficient emotional weight.

More importantly: Elliott’s scenes are strong because Krzykowski, as a director, consistently plays to Elliott’s strengths as an actor. Calvin’s dialogue is never as important as the periodic twitch of Elliott’s mustache, his mischievous squint, or his refreshingly flat line delivery. And Calvin’s story is thankfully never as important as Elliott’s magnetic screen presence, which makes it easier to follow Calvin wherever Krzykowski’s insane story takes him.

You can tell that Krzykowski loves and admires Elliott from the way he films Calvin’s first scene. Nosy, but well-meaning bartender George (Alton Fitzgerald White) asks Calvin why he doesn’t move some place where he can relax and fish. Calvin matter-of-factly growls that he hates fishing. He adds that he just might quit drinking and never come back: “What do you think of that?” George knows he offended his friend, so he calls after Elliott’s antihero when Calvin heads for the door: “See you tomorrow, Calvin?”

You know Elliott means it when he, in character, sighs: “See you tomorrow, George.”