Feel Like You’ve Lost Control Of Your Data? A Washington Lawmaker Wants To Change That

Listen

Following in the steps of the European Union and California, Washington lawmakers are considering a sweeping data privacy proposal that its sponsors say could become a model for the nation.

“I think that this is a historic moment,” said state Sen. Reuven Carlyle, a Seattle Democrat and prime sponsor of the Washington Privacy Act. “There is a global movement associated with enhancing consumer and individual rights to control your own data.”

The measure would give Washington consumers the right to access their data from companies that collect it and request corrections if they find errors. Under certain circumstances, consumers could also request that a company delete their data. And it would allow people to object to the sale of their data to third parties for purposes of direct marketing.

“This law is just an effort to get people control over the data that they are giving away in order to run their lives,” said Alex Alben, the state’s chief privacy officer.

Alben said he’s been all over the state — from community colleges to senior centers — talking with people about privacy. He said he’s been hearing a lot of concern.

“In short, they really feel like they’ve lost control over their data and they’re extremely frustrated,” Alben said.

The proposal in Washington is modeled after the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that went into effect last year. That regulation aims to put European consumers back in the driver’s seat when it comes to their data.

Here in the U.S., Congress has not passed similar legislation. As a result, Carlyle said states are looking to Washington — home of companies like Amazon and Microsoft — to lead on this issue.

“Because the federal government has been functionally illiterate and incompetent in this area and can’t pass anything, it falls on the states more than anything to appreciate the importance of data protection and privacy,” said Carlyle who chairs the Senate Environment, Energy and Technology Committee.

Last year, the state of California passed a digital Consumer Privacy Act. But Carlyle said his proposal hews more closely to the European set of regulations, which he described as an emerging global standard. Last May, Microsoft said it was extendingkey rights under GDPR to consumers around the world.

“This is a critical moment on the issue of privacy protection,” said Microsoft’s Julie Brill, a former commissioner at the Federal Trade Commission.

At a recent public hearing for Carlyle’s bill, Brill offered Microsoft’s support for the measure.

“Today, there is an urgent need for new privacy laws that provide strong protections for consumers within a framework that empowers them … but also enables innovation to thrive,” Brill said.

But not all companies and industries are convinced the proposal before the Washington Legislature hits the mark.

Lobbyists and representatives from the retail, data broker, telecommunications and technology sectors all weighed in with concerns during the public hearing. Most said they fear a “patchwork” of regulations from various states and would prefer a federal solution. Barring that, the industry consensus was that the bill is a work in progress.

The proposal in the Washington Senate would exempt companies that control and process the data of fewer than 100,000 consumers. But industry representatives said many small and midsize businesses would still meet that threshold.

Michael Schutzler, CEO of the Washington Technology Industry Association, noted that some U.S. companies block European customers so that they don’t have to comply with the EU privacy law. He warned that if Washington passes an onerous law, companies elsewhere might block Washington customers to avoid complying with the state law.

“That would be an unsuccessful outcome of your very hard work,” Schutzler told the committee.

State Sen. Doug Ericksen, the ranking Republican on the Senate Environment, Energy and Technology Committee, cautioned that Washington might be putting itself at a competitive disadvantage if it passes a stringent data privacy measure.

“My concern on legislation of this type is always you know becoming an island, becoming isolated,” Ericksen said.

But there are also those who say the Washington Privacy Act — as currently written — doesn’t go far enough.

Of particular concern to some is the use of facial recognition. The bill before the Washington Legislature seeks to restrict government and police use of this technology. But shopping malls, for instance, could deploy facial recognition as long as consumers were notified.

“I believe that we’re united in the goal of having real protections for consumers, but in order to get there, there is a need for a stronger bill,” said Eric Gonzalez Alfaro of the ACLU of Washington.

Some police groups, however, say the restrictions on facial recognition go too far.

“When applied to a local law enforcement agency like the Port of Seattle, it may in fact prohibit the use of facial recognition to enforce the no-fly list or the terrorist watch list,” said James McMahan of the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs.

In addition to the Washington Privacy Act, Sen. Carlyle has also introduced legislation to restrict the sale of consumer data by state agences. In the Washington House, Republican state Rep. Norma Smith has introduced a bipartisan bill to regulate the data broker industry.

Copyright 2019 Northwest News Network

Related Stories:

Washington state bill could strengthen regulations, increase fines for ‘troublesome’ landfills

While hiking, Nancy Lust, with Friends of Rocky Top, watches a truck dump waste into a landfill in Yakima County. Lust lives near the landfill and has fought to learn

This bill could give Washington tribes, communities more say in wind, solar development

A new bill making its way through the Washington Legislature would require county and tribal approval for new wind and solar projects that go through the state’s Energy Facility Site

Washington state bill could change how rural communities could work to close a library

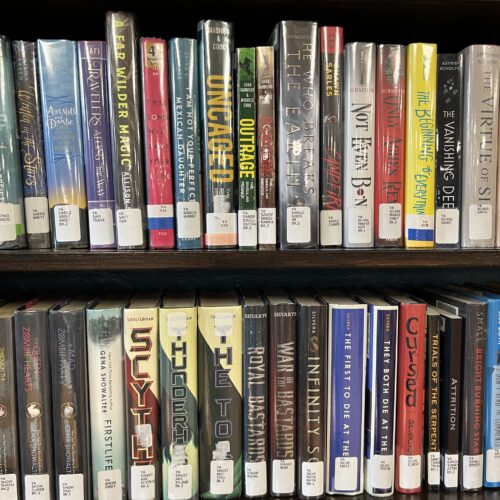

Young adult books at the Columbia County Library. Some people have requested to move the YA section into the adult section because of what they call “obscene” material in 100