BOOK REVIEW: ‘The Heartbeat Of Wounded Knee’ Seeks A New Narrative For Native Americans

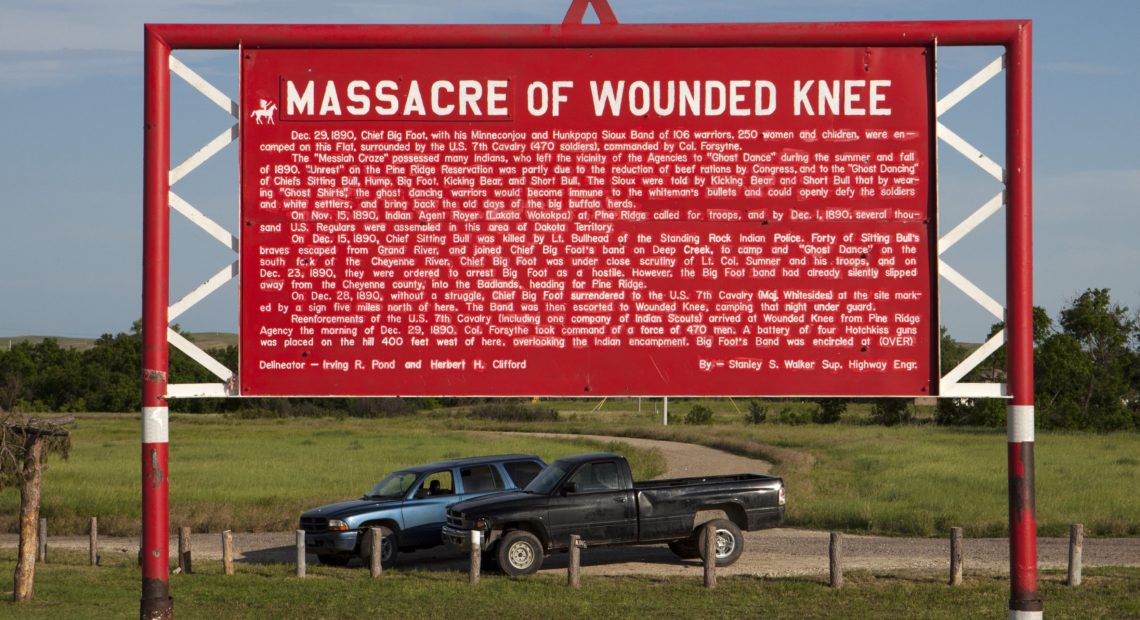

PHOTO: Memorial to the Wounded Knee Massacre that occurred on Dec. 29, 1890, near Wounded Knee Creek on the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, South Dakota. CREDIT: VW Pics, UIG via Getty Images

BY TOM BOWMAN, NPR

In the 1970 work by Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, the author — a non-Indian with seemingly little connection to any current tribes — declared that “the culture and civilization of the American Indian was destroyed” during the late 1800s.

Not so fast, says author David Treuer.

Treuer calls his new book, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present, a “counternarrative” to Brown’s classic — which sold millions of copies with its story of U.S. government betrayal, forced relocation and massacres.

“The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee

Native America from 1890 to the Present”

by David Treuer

Treuer recalls reading Brown’s book while in college in the 1990s and being dismayed by the tales of Indian reservations as nothing more than worn places of hopelessness and squalor. A member of the Ojibwe Tribe from Minnesota with a Ph.D. in anthropology and several novels under his belt, Treuer tells of the tug of family and tribe and the lure of the north woods at his Leech Lake Reservation.

As Treuer shows, the Indians not only have maintained their culture and civilization through some dark years — but in some parts of the country, today, are thriving. The heartbeat is strong. He writes:

“I came to conceive of a book that would dismantle the tale of our demise by way of a new story. This book would focus on the untold story of the past 128 years, making visible the broader and deeper currents of Indian life that have too long been obscured.”

Treuer begins with a swift look at the beginnings of European contact, with its endless tales of kidnappings, rapes, broken treaties and armed attacks. But he shows that in each and every part of the country, Indians hung on.

This retelling is the weakest part of the book, although there are some nice historical tidbits: Gen. George Washington was called Hanodaganears — “Devourer of Towns” — by the Iroquois of upstate New York for his scorched-earth policy toward the British allies.

The author shines, instead, when he heads out on the road to meet with his relatives at Leech Lake or members of other tribes across the United States. There is a delightful collection of characters. Intrepid entrepreneurs, savvy lawyers and others who work for the best interests of their tribes.

People like Sierra Frederickson in North Dakota, a writer and teacher at a community college, who uses social media to connect members of her tribe. Or Bobby Matthews of Leech Lake, who hunts, traps and harvests near the lake. Or Sean Sherman, a Sioux chef, who takes Treuer to an organic farm that grows “historical indigenous varietals,” everything from Cherokee beans to Oneida corn to Lakota squash, to sell at casinos and restaurants the tribe owns, as well as to private homes.

“The American Indian Dream is as much about looking back and bringing the culture along with it as it is about looking ahead,” Treuer writes.

Treuer is not afraid to take on some of the more high-profile Native Americans, including addressing corruption among the hierarchies of some tribes and the leadership of the American Indian Movement, a radical and sometimes violent group from the 1960s and 1970s. He says many Indians muttered under their breath that AIM really stood for “Assholes in Moccasins.” It was the “destructive antics of its leadership, which hurt a great many people.” But AIM also energized Indians to the “radical notions” that they don’t have to accept their position of disenfranchisement.

That energy created homes for low-income urban Indians, on-site day care and health care, and Indian-centric cultural programming. Programs teaching vanishing languages are on the rise, he says. And more and more people are claiming Indianness than ever before.

The federal government that once lied, cheated and attacked the Indians finally in the late 1970s helped turn things around for the tribes, Treuer says. There was the Carter-era American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, which allowed tribes to exercise religious traditions.

“The effect of the act was profound,” Treuer writes. “Younger and urban Indians had a chance to discover and participate in traditions that had been lost to them.”

This was followed by something else also profound — and lucrative: the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, signed by President Ronald Reagan, which codified the process for tribes to administer gambling. Many Indians refer to “BC” — before casinos — he says. It has had as defining an effect on the social and economic lives of Indians, Treuer writes, as the mass migration of Indians to cities during the past 50 years.

Of the more than 500 federally recognized Indian tribes in the U.S., fewer than half — 238 — own and run gaming operations. Revenues grew from $100 million in 1988 to more than $26 billion in 2009. It works better for some tribes than others, Treuer says, noting that some tribes create museums, jobs programs, schools and cultural centers. Also, some tribes share the vast wealth among their members. But it has not helped all Indians. Unemployment is still high, especially in the northern Great Plains, with unemployment rates as high as 77 percent.

“The contrasts, while extreme, shouldn’t be surprising. This is America, after all,” he writes, with all but a shrug. “Like all American avenues to wealth, casinos privilege the few and leave out the majority.”

Treuer said he wrote the book to show that Indians lived on after Wounded Knee “as more than ghosts and more than the relics of a once happy people.”

“I have tried to catch us not in the act of dying but, rather, in the radical act of living,” he writes.

He succeeds in this fine and timely work. It will certainly help usher in a new narrative for Native Americans.