Would You Want To Be Composted After You Die? Washington Lawmakers Consider Making It Legal

Listen

No one expressed strong opposition to the human composting bill at its initial hearing in front of the state Senate Labor and Commerce Committee.

“It is quite remarkable,” Democratic state Sen. Jamie Pedersen, who sponsored the measure under consideration in Olympia, said of the idea.

If you died tomorrow, the legal options to lay to your body to rest in Washington state would be burial or cremation. But supporters of human composting, which they refer to as “recomposition,” say this is a greener way to go after you die.

Bellevue, Washington, resident Hanna Floss testified she wants to have as much of a low environmental impact in death as in life.

“I would love my last gesture on Earth to be natural and productive,” Floss said. “Hopefully, many years from now, I would like my remains to be turned into soil to provide nourishment to plants.”

Close up of the composting vessel used in 2018 research trial at Washington State University. CREDIT: WSU COMMUNICATIONS

The human composting movement in the Pacific Northwest largely grew out of a master’s thesis project from Seattle designer and entrepreneur Katrina Spade. A subsequent fellowship launched a nonprofit, the Urban Death Project. In 2017, Spade transitioned the effort to a startup company in Seattle called Recompose to refine and commercialize the process.

The legalization and commercialization drive got a boost from a research trial last year at Washington State University. A team led by Professor Lynne Carpenter-Boggs, a compost science expert, demonstrated that bodies could be safely and efficiently converted to “earthy organic material” that is unrecognizable as human remains. The 2018 research used six bodies that were donated to the university for science.

Recompose CEO Katrina Spade, left, with WSU Prof. Lynne Carpenter-Boggs.

CREDIT: WSU COMMUNICATIONS

The human composting process Spade described to the Legislature involves placing bodies in vessels where they can be covered in wood chips and straw. The rotating vessels would then be aerated as well as temperature- and moisture-controlled to help naturally-occurring microbes and bacteria break down the human remains — including teeth and bones. Spade said after about 30 days, the accelerated decomposition yields about one cubic yard of soil compost per human body.

“In addition to being safe, recomposition is natural and sustainable,” Spade told lawmakers. “It provides significant savings in carbon emissions, which is especially important because Washington has the highest rate of cremation in the country at 76 percent.”

“Cremation requires fossil fuels and has significant carbon dioxide emissions,” Spade continued. “Recomposition uses one-eighth the energy of cremation and saves over a metric ton of carbon dioxide per person who chooses it.”

Sen. Pedersen’s legislation doesn’t only cover human composting: It also authorizes alkaline hydrolysis, a different flame-free funeral option that involves dissolving a body in water and lye under heat and pressure. Nineteen U.S. states — including Idaho, Oregon and California — already allow alkaline hydrolysis, which is sometimes marketed as “bio cremation.”

Several funeral and cemetery association leaders took a neutral position in their testimony to the state Senate, but said the state should set tight rules for where human compost could be spread.

“I would be hopeful that we would have firm laws about that until we are more comforable with how that material is presented,” said funeral director Lisa Devereau of Vashon Island.

Copyright 2019 Northwest News Network

Related Stories:

Washington state bill could strengthen regulations, increase fines for ‘troublesome’ landfills

While hiking, Nancy Lust, with Friends of Rocky Top, watches a truck dump waste into a landfill in Yakima County. Lust lives near the landfill and has fought to learn

This bill could give Washington tribes, communities more say in wind, solar development

A new bill making its way through the Washington Legislature would require county and tribal approval for new wind and solar projects that go through the state’s Energy Facility Site

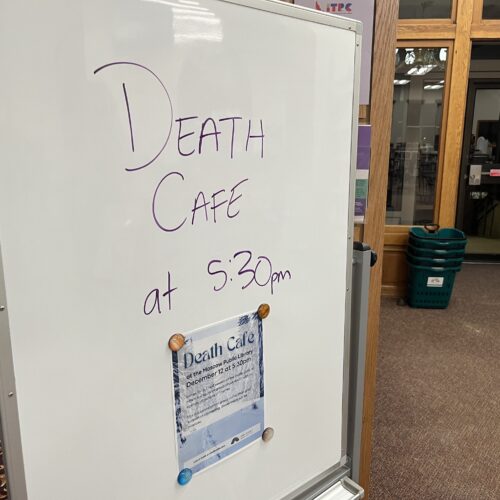

Death Cafes offer a space to discuss the end of life

Death Cafes give people a place to talk openly about the end of life. (Credit: Phineas Pope / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 0:54) Read Around the world, people gather at places