Gingerbread Cred: Bakers Craft Winning Edible Art Down To The Last Detail

PHOTO: For this year’s grand prize winner, the judges were impressed by the intricate, working gingerbread gears of the clock inside Santa’s workshop. CREDIT: Kristen Hartke/NPR

BY KRISTEN HARTKE

Nadine Orenstein never expected to judge gingerbread houses. But several years ago, the curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art happened to see a program on the Food Network about a competition in Asheville, N.C., and was intrigued by the intricate — and edible — Christmastime entries. She happened to mention the show to a colleague, who happened to know one of the judges, who happened to be on the lookout for a new judge to add to the panel.

The rest, as they say, is history. Fourteen years later, Orenstein is still a judge for the National Gingerbread House Competition, which in November celebrated its 26th year at Asheville’s Omni Grove Park Inn. “In a way, it’s very similar to what I do as a career and, in some ways, completely different,” she says.

Two edible mice type up an edible letter to Santa on an edible typewriter on an edible desk. CREDIT: Kristen Hartke/NPR

When it comes to judging, however, it’s the details that loom large, even when they might only measure a few millimeters. Nothing escapes the eagle eyes of the judges, from a wall that is just slightly off-kilter to meticulously hand-painted playing cards.

The competition didn’t originate as a contest in 1992, but as simply a display of gingerbread houses made by Asheville locals. “It really was just a fun thing that we did at the inn,” says Tracey Johnston-Crum, Omni Grove Park’s director of public relations. “At one point, someone asked, ‘Which one is the winner?’ and the idea began to grow.” This year, there were 195 entries from across the U.S. and Canada, which means that judging this contest is no cakewalk.

Other than Orenstein, most of the eight judges come with a serious pastry pedigree, like Mark Seaman, master sugar artist for Barry Callebaut chocolate company, one of the world’s largest cocoa producers. Seaman has been judging the competition for over a dozen years.

“It is a long and somewhat complicated process,” he says. “Some people are literally spending hundreds of hours creating their entries, so we want to pay attention to the work they’ve put into it, but we also have to do all the judging in one single day.”

It’s a boring old spreadsheet that saves the day, especially when there are nearly 200 entries in four categories (child, youth, teen and adult) to consider. Using specific criteria — creativity, difficulty, overall appearance, consistency of theme, and precision — each judge starts the morning by spending two hours choosing 10 favorites in each category. The competition staff collects the information, plugs it into Excel, and tabulates the first round of results, narrowing it down to a universal top 10 entries. Then the judges really get down to business, parsing the technical difficulty and design elements in half-points — numbers that go back into the spreadsheet for the final result.

But while the competition relies on numbers to achieve fairness — sometimes the grand prize winner isn’t even selected by all the judges as one of their initial top 10 favorites — it’s ultimately a combination of technique and creativity that determines the winners. And to make it into the top 10, contestants have their work cut out for them.

For Seaman, craftsmanship is a key element, particularly when he sees something especially innovative, like this year’s grand prize winner, which depicts Santa’s workshop with a clock made of functional gingerbread gears. The gingerbread was baked by creators Julie and Michael Andreacola, of Indian Trail, N.C., for several hours, then precision-cut with lasers.

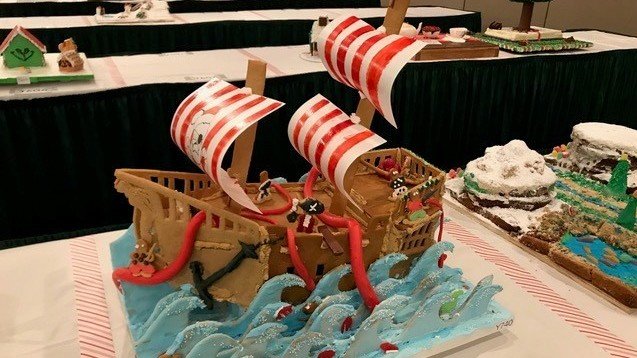

The gingerbread competition is not limited to houses — dragons, pirate ships and bonsai trees are also welcome.

CREDIT: Kristen Hartke/NPR

“When we discovered that all the gears could move,” enthuses Seaman, “I just thought, ‘Somebody here has a really impressive engineering background that they were able to apply to food.’ Every year, I learn something new, how to do something I’ve never thought about.”

While Orenstein finds the technical elements impressive, she is also looking for a compelling story, just as she would in any piece of art on display at the Met. The difference, however, is that perfection is more important in gingerbread than it is in fine art. “Sometimes, the lack of perfection is key in art,” says Orenstein, “but what I’ve learned over time is that perfection in these gingerbread houses matters. There are ones that you look at the first time and you think, ‘This is amazing,’ but then you go back to look for the details, and you realize it just isn’t enough.”

Those details might be the tiny copper Moscow mule mugs that grace a table where a group of reindeer are playing a game of poker, the labels on the cans lining the walls of a general store — all edible, mind you — or realistic-looking candles made of white chocolate that stand next to a gingerbread clock. But an impressive-looking bonsai tree, complete with an ornate “porcelain” pot and hundreds of tiny leaves, failed to impress the more experienced judges. “At first, you look at it and think it’s amazing, but it’s the closer look that changes your mind,” Orenstein says.

Johnston-Crum agrees, saying, “As beautiful as the bonsai tree was, it didn’t really tell a story. That’s what separates the winners.”

“You don’t enter a competition because you want to win,” says Seaman. “You enter because you want to do the best work you can possibly do. The people who win are attached to the piece in some personal way. Even though the technique is really important, you shouldn’t learn how to do hot sugar just for the purposes of entering this contest.”

However, learning how to precision-cut gingerbread with lasers might not be a bad idea.

Kristen Hartke is a food writer based in Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit npr.org