A First Glimpse Of Hanford’s Tunnel 2 As Work Continues To Prevent Another Hazardous Collapse

Listen

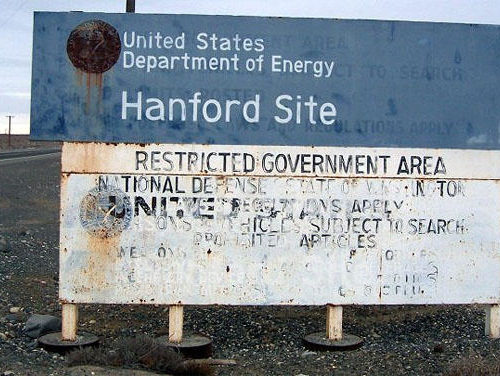

In the middle of Washington’s desert, there’s a tunnel that stretches a third of a mile underground.

It’s full of railcars with chemical and radioactive waste. Now, contractors at the Hanford cleanup site are racing to fill the tunnel with grout, because they don’t want it to collapse.

In May 2017, another nearby tunnel of waste partially caved in, sending the Hanford site into emergency lockdown.

I got a rare first look at the tunnel this week, since that partial collapse of Tunnel 1.

Near Tunnel 2 you can see that it’s buried under 8-feet of desert sand. In there are 28 rail cars full of radioactive-contaminated equipment. It all came from a massive nearby plutonium extraction plant called PUREX, operated during the Cold War.

Recently, Tunnel 2 was deemed unsafe by federal engineers. The partial collapse of Tunnel 1 led to the federal investigation and the decision to seal up both tunnels with grout.

The worry: A plume of radioactive dust could be thrown up or other contamination could escape from a collapse, endangering workers and the public.

Mark Wright is the vice president with the Hanford contractor doing this work, CH2M HILL Plateau Remediation Company.

Mark Wright, vice president with CH2M HILL Plateau Remediation Company, a Hanford contractor, stands in front of Hanford’s Tunnel 2 where workers are grouting it closed. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

Each week near Tunnel 2, large concrete trucks drive in a nearly four-mile clockwise circuit – around and around like a merry-go-round.

The truck drivers talk to each other by honking before they move or back up. It sounds sort of like a chorus of big-rig horns.

At the work yard, called the batch plant, where they mix up the grout for the tunnel, workers combine sand, fly ash and cement together with water in the big trucks to form the right consistency. It has to be stable enough to do the job, but thin enough to flow down the long tunnel where workers can’t go.

After loading, the trucks are driven slowly over to the tunnel.

There are six ports on the tunnel where workers can pump in the grout. And big pump machines and booms carry the grout from the trucks into the tunnel.

The pump truck whines and gurgles as the grout is carried to its destination.

The grout sets up in layers, and workers will keep pouring for months until the tunnel is filled up like a giant cannoli.

A monitor screen near Tunnel 2 at Hanford shows the grout being poured into the structure underground in real time. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

So far, about 2,300 truckloads of grout have been pumped into the tunnel. That means the crew is about at the halfway point.

At a camera viewing station – basically a pop-up tent with a flatscreen on a folding table – the screen shows what a remote camera is capturing. In grainy black and white, the gurgling grout splashes down inside the tunnel. Wright says the pour isn’t exactly level yet.

“It will tend to build up at certain locations,” Wright says. “So we have kind of a sort of a dune profile going on right now, sort of like slow rolling dunes down there. So, the engineers have laid out a plan to keep that as level as we can until we get up to the top, and then we can top it off.”

But some people and groups aren’t as sold on the plan. Northwest tribes and others say pouring all that grout into the tunnel will render it a permanent shallow radioactive waste dump, that it would be so difficult or costly to cut up and remove, it will rest there for all time.

Wright says the grout is a special mixture – precisely so it’s sturdy, but could be cut up and moved.

“When [the U.S. Department of Energy] selected the grout they wanted the option that this is not considered a permanent disposition,” Wright says.

Going forward, winter weather will be the main X factor as the crew nears completion of sealing up this tunnel. March is the project’s finish line. It’s going to take about 5,000 truckloads to get there.

Related Stories:

Hanford Workers Get ‘All Clear’ After Shelter Indoors Order During Tunnel-Filling Operation

Officials at the Hanford Nuclear Site ordered workers to stay indoors Friday morning as a precaution. They discovered steam rising from an unexpected part of a tunnel filled with highly contaminated waste. By mid-day, officials had announced they found no contamination.

State And Federal Regulators Discuss New Plans For Cleaning Up Hanford Waste

Federal and state energy regulators will hold back-to-back meetings in Portland and Seattle for a proposal to reclassify some of the high-level nuclear waste at the Hanford Nuclear Site.

Works Starts On Grouting 2nd Waste-Filled Hanford Tunnel, With Aim Of Preventing Another Collapse

Work began this week to fill a roughly 1.3-mile-long tunnel with grout at the Hanford Nuclear Site. The tunnel is filled with highly hazardous radioactive waste.