Scent Research Could Help More Salmon Find Their Way Home

Listen

BY JES BURNS / OPB

It turns out, this could be helpful information to know when you’re trying to figure out how to keep salmon raised in hatcheries from interbreeding with wild fish – a phenomenon called “straying.”

It’s a problem that occurs at salmon hatcheries everywhere in the West. But it’s particularly concerning on Southern Oregon’s Elk River, where efforts are underway to preserve the small population of wild native chinook salmon.

The Problem

Things get a little hectic around 9 p.m., when a salmon hits the entanglement net stretched across a cold and windy stretch of the Elk River near Gold Beach, Oregon. The floats on the choppy surface begin to shake and bob as the fish struggles to get free.

ODFW’s Matt Deangelo takes scale samples from a jack chinook as part of salmon tracking work on the Elk River. CREDIT: JES BURNS/OPB

“We’ve got a fish!” yelled Jenn Ambrose, a fisheries technician with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Two of Ambrose’s colleagues on a salmon-tagging team sprint into the water.

“Even after doing this for five years, you still get that adrenaline,” Ambrose said from the gravel bank.

Using a headlamp to see in the dark, they successfully free the salmon and bring it over to a live well on the riverside.

It’s a female fall chinook, still vivid silver from its time in the ocean. Like all Pacific salmon, it’s used a mix of magnetic and olfactory – or odor – information as a map to get back to this river where it was born and make the next generation of chinook in the Elk River.

Team leader Austin Huff checks to see if its fin is clipped, indicating whether it was born wild or at the Elk River Hatchery about 12 miles upstream.

“There’s no mark. It’s a wild fish,” he said.

He then opens the mouth of the salmon and smoothly inserts a radio tracking tag into the fish’s stomach.

“It’s a relatively non-invasive, you know, better than surgery,” Huff said. “As they’re hitting the river system, their esophagus is actually closing up. They’re finished eating for their life in anticipation of their spawning. And because of that they will keep the tag within their stomach cavity and carry it all the way upriver.”

ODFW’s Austin Huff inserts a radio tag into the stomach of an adult Chinook salmon. The agency is tracking where the fish are moving once they enter the river. CREDIT: JES BURNS/OPB

The team is tracking the movements of wild and hatchery chinook salmon to see where they travel and spawn within the Elk River.

“The idea is to keep the wild fish wild and hatchery fish in the hatchery,” Huff said.

But in this river, there’s a good chance this wild female chinook will end up mating with a hatchery-raised fish. Too good of a chance.

Too Many Strays

The Elk River Hatchery was built back in the late 1960s to generate more salmon for fishermen – both commercial and recreational. The effect the hatchery would have on the native run of fish on the river wasn’t known or even a consideration at the time.

And it turns out, there are miles of fantastic spawning grounds downstream of the hatchery – something the captive-reared fish immediately figured out.

The first year the hatchery fish came back, the best available fish counts from ODFW showed they outnumbered the wild fish on the spawning grounds 2-to-1. Five years later, that ratio was 4-to-1.

Salmon waiting to spawn at the Elk River Hatchery near Gold Beach, Oregon. CREDIT: JES BURNS/OPB

The numbers fluctuate from year-to-year, sometimes widely, but the percent of hatchery salmon on spawning grounds used by wild salmon hit 80 percent as recently as 2002.

“We know that [hatchery] fish, when they come back and reproduce, they produce fewer surviving offspring than wild-origin fish,” said David Noakes of the Oregon Hatchery Research Center.

The state considers the interbreeding wild and hatchery fish a significant threat to the native fish on the Elk River.

“What’s changed is our priorities and outlook. We’re collectively paying more attention to conservation of native runs of fish than we did,” said Shannon Richardson, with ODFW’s Coastal Chinook Research and Monitoring Program.

In the state’s most recent management plan, Elk River chinook salmon were considered “non-viable,” in part because of the high number of strays from the hatchery. The state immediately cut the number of salmon the hatchery could release. And it gave the Elk River Hatchery a 2021 deadline to significantly cut the stray rate, or face further cuts.

And less fish for fishermen to catch could be a hit for the coastal economy on the southern Oregon coast, which relies heavily on fishing and tourism.

Steps taken in the past few years on the river have already started bringing down the average stray rate to about 42 percent. But the state’s target is 30 percent. And that’s still a pretty big gap to cross.

Leading Them By The Nose

So how do you control the behavior of fish swimming free in the ocean or rivers?

This is where OSU’s Maryam Kamran and her bouquet of smells comes back in.

Kamran wants to tap into the adult salmon’s amazing ability to find its way back to the stream where it hatched.

“In the natural environment, they’re using what we call a navigational toolkit,” she said.

Salmon are believed to use the earth’s magnetic field to find their way in the ocean. But then once they’re in freshwater, they switch over to scents in the river to hone in on the specific spot where they were born.

“You probably had the experience of going back into some building, you were there years ago, and you close your eyes and say, ‘I remember this is the chemistry lab or this is the library or this is my grandmother’s kitchen.,’” said Kamran’s advisor, David Noakes. “But you have that sensation and come back and say, ‘I recognize this.’ That’s what the fish are doing.”

Kamran said a solution for the Elk River Hatchery may be to redraw that sensory map the salmon use to find their way. In other words, she wants to give the Elk River Hatchery a distinctive aroma salmon can learn as babies and follow home as adults.

“Their noses are really great. They can detect a small set of molecules or chemicals and they can detect them at really low levels,” Kamran said. “So kind of like dogs, but not such a wide range. There’s only a few things that they pay attention to.”

She tried dozens of scents to find just the right one. Through a series of experiments, she identified an amino acid that doesn’t exist naturally in the Elk River. And her test fish responded to it well.

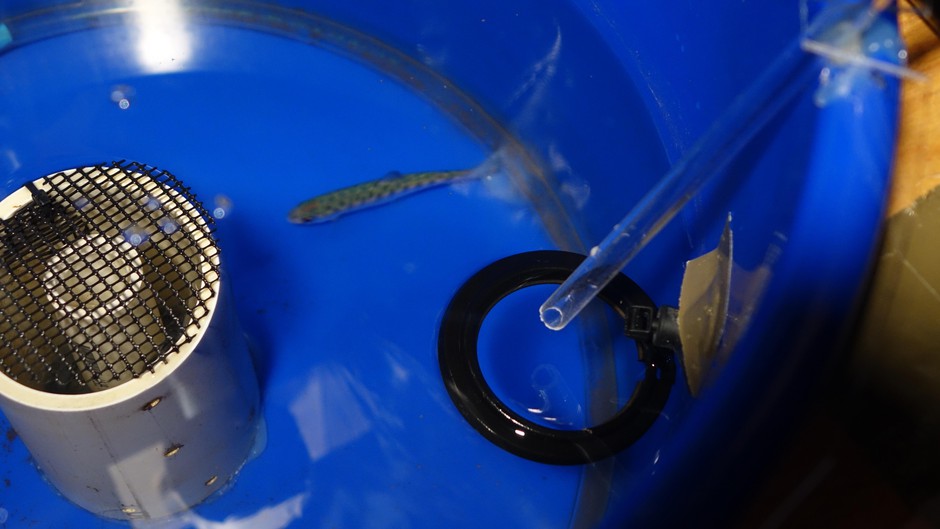

Baby salmon are exposed to a scent at the Oregon Hatchery Research Center in a project designed to cut back on hatchery fish straying. CREDIT: JES BURNS/OPB

“Sure enough, they actually started to pick it up the first day,” she said.

Her next step is to try her theory out next fall at the Hatchery, where the baby chinook salmon will be exposed to her special scent. She’s spent the past summer trying to figure out the minimum amount of the scent and the minimum number of times young fish needed to be exposed in order to imprint on the unique smell.

“The idea is we tell hatchery manager, ‘This is your odor. This is how much you need to add. And this is how often you should put it in the water when the fish are exposed.’”

And then three years later, when the adult hatchery chinook salmon are due back from the ocean to spawn, the hatchery will release trace amounts of that odor – fragrant breadcrumbs the salmon can follow upstream to the holding tanks where they were raised.

And if Kamran is correct, the hatchery fish will pass up a chance to get lucky with the wild salmon, and instead, seek out the sweet, sweet smell of home.

Copyright 2018 Oregon Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Ocean conditions mixed for salmon, leading to average salmon returns

NOAA biologist Brian Burke says mixed ocean conditions may lead to average salmon runs, but climate change is disrupting ecosystems—making continued research critical.

Canadian leaders hope trade negotiations won’t derail Columbia River Treaty

A view of the Columbia River in British Columbia. The Columbia River Treaty is on “pause” while the Trump administration considers its policy options. However, recent comments by President Donald

Snake River water, recreation studies look at the river’s future

People listen to an introductory presentation on the water supply study findings at an open house-style meeting in Pasco. After they listened to the presentation, they could look at posters