Here A Wolf, There A Wolf, Everywhere A Wolf, Wolf. Public Sightings Abound In The Region

Listen

The Oregon and Washington state wildlife departments welcome more eyes on the woods to monitor the spread of wolves, even though a good number of the citizen sightings are probably mistaken.

Retired teacher Ed Kenney is virtually certain he saw a wolf snooping under an apple tree behind his log cabin last Thursday morning.

“It took awhile for me to realize that it was a wolf,” Kenney said. “All of a sudden I thought, ‘Oh my God, that’s a gray wolf!'”

The nearest confirmed wolf pack to Kenney’s rural home southeast of Yelm, Washington, is over the Cascade Crest — nearly 100 miles away.

“It was big. It was really huge,” Kenney continued. “It dwarfed my dog, maybe double the size. So I’m thinking 80 to 100 pounds — one of these beautiful gray animals like you see in the pictures.”

Kenney reported his observation to Washington’s Department of Fish and Wildlife. The sighting joins several hundred other citizen sightings this year from every corner of the state.

The Washington and Oregon wildlife departments said many of the reports they got were probably coyotes or dogs in reality.

“A good chunk of those may be misidentification, which is OK,” said Ben Maletzke, a wolf specialist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

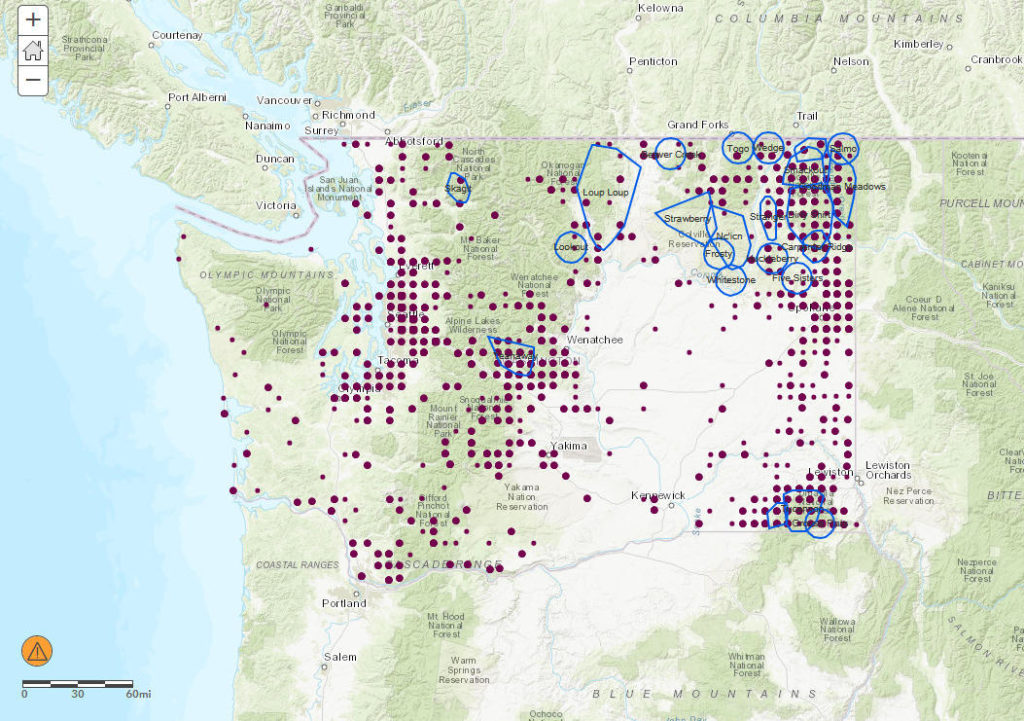

He keeps an open mind as he sifts the incoming reports for clusters of sightings that might reveal a new pack.

“Just about anywhere in the state is possible for a wolf to move through … because wolves are highly mobile,” Maletzke said in an interview Monday. “We’ve had dispersers go 400 to 600 miles up into B.C. We’ve had them leave from Washington and go all the way to Yellowstone.”

Kenney acknowledged how common coyotes are, but said he had not seen them in his country orchard much before.

“That’s what I was suspecting, just because of the shape of the animal, but it was way larger than a coyote,” he said about his observation out a window from the safety of indoors. “The whole encounter lasted less than a minute. I was pretty thrilled.”

Asked about Kenney’s report specifically, Maletzke said it cannot be ruled out as a wolf.

Maletzke said citizen reports are most helpful when the sighting is accompanied with a photo or video of the animal. Pictures and measurements of a footprint also can help biologists assess what the observer may have seen.

Maletzke said he is focusing right now on sightings along the Cascade Crest, roughly from the North Cascades Highway down toward Interstate 90.

“I would expect more packs to fill in in those areas,” Maletzke said. “There’s a higher probability because there are packs already established in some of those areas.”

“That said, the Teanaway [pack] formed a long ways from any nearby packs,” Maletzke continued in reference to a wolf family in Kittitas County, Washington. “It’s not uncommon for wolves to disperse to a new area and for two to find each other and set up with some distance in between.”

In its most recent annual report on wolves and wolf management, Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife reported it too is getting increasing numbers of wolf sightings from the public. Last year, it received 397 wolf sighting reports statewide, either called in to a biologist or through an online reporting portal.

“Subsequent follow-up of some of these public reports yielded valuable information about new wolf activity or existing groups without radio-collars,” the agency said in its 2017 annual report.

In September last year, ODFW put a “wolf versus coyote” identification quiz online to educate hunters in particular. The agency said its “Canid Quiz” has been accessed tens of thousands of times.

Gray wolves are protected under state law throughout Oregon and Washington and are federally listed as an endangered species in the western two-thirds of Washington and Oregon. In the non-federally listed eastern zones, wildlife managers and ranchers have some latitude to kill wolves that attack livestock.

There were approximately 120 wolves each in Oregon and Washington at last count, with most of the population concentrated in the northeast corner of each state.

Purple dots represent wolf sightings by the public reported since 2012 to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Blue lines encircle confirmed wolf packs. CREDIT: WDFW

Related Stories:

Complaint to federal agency over Washington animal organization

In Skagit County, a nonprofit that houses a number of animals, including exotic ones, is in continued legal battles. A law firm that advocates for animal rights is claiming the organization may have violated the Endangered Species Act, by, as the law firm claims in its complaint, the illegal euthanization of wolves.

Wolves remain endangered in Washington state

Washington state’s Fish and Wildlife Commission voted to keep gray wolves’ endangered status. (Credit: William Campbell) Listen (Runtime 0:54) Read Gray wolves will keep their endangered status in Washington state.

Nez Perce Tribe honors the wolf

In this Feb. 1, 2017, file image provided the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, a wolf pack is captured by a remote camera in Hells Canyon National Recreation Area