Washington Tribes Oppose Canadian Pipeline, More Oil Tankers In Salish Sea

Read On

BY JOHN RYAN / KUOW

Tribal leaders and members from Washington state crossed the Salish Sea to oppose a pipeline that could bring more oil tankers to waters on both sides of U.S.-Canada border.

The Canadian government wants to expand the Trans Mountain Pipeline and triple the flow of oil from Alberta to the Pacific coast.

Members of the Lummi, Suquamish, Swinomish and Tulalip Tribes made the trip to Vancouver Island to support their Coast Salish relatives north of the border – and their relatives under water.

“Our relatives, the salmon and the killer whales, do not recognize this border,” Tulalip Tribes chair Marie Zackuse told Canada’s National Energy Board at a hearing in Victoria on Wednesday. “As Tulalip people, we share a sacred cultural bond with the killer whales. They are the symbol of our tribe, and it is our responsibility to speak up for them when they are in need.”

Canada’s Federal Court of Appeal halted the pipeline project in August after finding that the Canadian government failed to address the expanded pipeline’s aquatic impacts—from ship noise to oil spills—and for failing to consult with indigenous nations along its route from the prairies of Alberta to the hunting grounds of southern resident killer whales.

Since then, Canada’s National Energy Board has devoted 11 days to listening to indigenous nations all along the pipeline route.

While other interested parties have commented in writing, the board recognizes that much indigenous knowledge is passed down orally, and allows First Nations, as they’re known in Canada, to participate in their traditional format.

“Sharing your traditional knowledge and stories about the use of your traditional territory is of value to us,” board vice chair Lyne Mercier said at the hearing’s opening.

Following their tradition, leaders of four Washington tribes started the hearing with a “paddle song” to let the energy board know that they came in peace. But they also said they were ready to fight for the waters they call the Salish Sea.

“I have to come up to Canada and express the fight I have in me to save these species, save our culture,” commercial fisherman and Swinomish tribal senator Jeremy Wilbur said.

“We see the salmon decline. We see the orca decline. Well, it’s going up the chain. Who’s next? What’s next? When’s it our turn?” he said.

With an expanded pipeline, tanker traffic from the Port of Vancouver could increase from the current five ships per month to 34.

Tribal speakers said that passing oil tankers already make it dangerous to be out in fishing boats in the tribes’ traditional fishing areas and that the tankers destroy gear like crab pots and and salmon nets.

“That’s not letting us continue our way of life,” Lisa Wilson with the Lummi Nation said.

According to pipeline operator Trans Mountain, oil tankers will remain a small fraction of the shipping traffic on the Salish Sea, even if the flow of oil through its pipeline is tripled.

In written submissions, the company has said that the risk of oil spills is “well-managed” and that the company has committed to all 17 measures recommended by a Canadian government panel to improve oil spill safety.

The increased tanker traffic would have “a negligible effect” on the frequency of oil spills in the Salish Sea, according to Trans Mountain.

“The operation of project-related vessels is likely to result in significant adverse effects upon both the southern resident killer whale and indigenous cultural uses of this endangered species,” Justice Eleanor Dawson wrote in the August ruling that forced the National Energy Board to reconsider the already-approved pipeline project.

The remaining 74 southern resident killer whales are protected in the U.S. by the Endangered Species Act and in Canada by the Species at Risk Act.

While a major oil spill could have a catastrophic impact on the struggling whale population, everyday noise from boats and ships interferes with their ability to hunt by echolocation. Ship noise compounds the problem of dwindling numbers of salmon for the orcas to eat.

“If you’ve ever been underwater when a tanker, one of these big tankers, or even a ferry, goes by, four or five miles away, you can hear it underwater,” said Wilbur, who earns part of his living in a non-traditional fishery: diving for sea urchins and sea cucumbers. “And not just hear it, you can feel it in your body.”

“One of the many reasons our southern resident killer whales are about ready to go extinct,” Wilbur said.

A two-month-long pilot program last year found that underwater noise levels along the Canada-U.S. border west of San Juan Island could be cut in half when big ships bound for the Port of Vancouver voluntarily slowed down.

A decision from Canada’s National Energy Board on the Trans Mountain Pipeline project is expected in February.

Copyright 2018 KUOW. See more on KUOW’s Orca Emergency series.

Related Stories:

Tribal members gather to demand U.S. Government fulfill treaty obligations

Sockeye salmon like these are among the salmon species in peril. (Credit: Aaron Kunz) Listen (Runtime 2:57) Read For Northwest tribes, removing the four lower Snake River dams means more

Bringing Indigenous languages into public schools

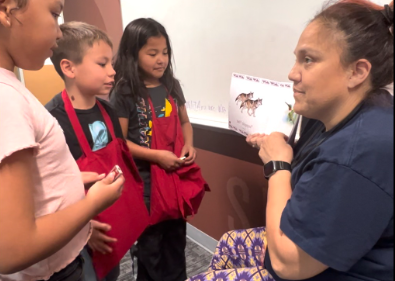

A number of Washington state public schools are partnering with tribes to bring Indigenous languages into classrooms in an effort to rectify the marred history of Native American boarding schools.

Rachael Barger is a teacher on special assignment with Bethel School District, one of the districts partnering with the Nisqually Tribe to bring its Southern Lushootseed language into the classroom for a small subset of students.

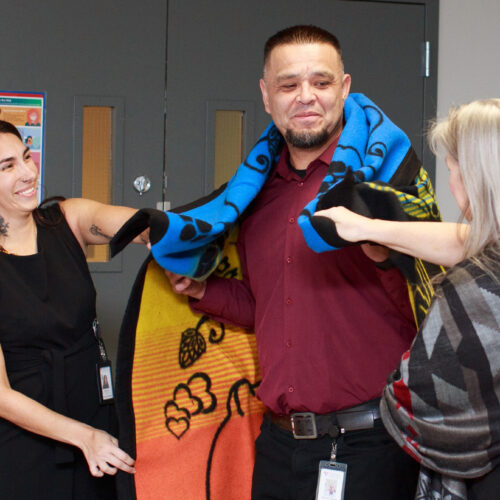

‘Native and Strong’ provides culturally-informed crisis support to Washington callers

Native and Strong crisis counselor Robert Coberly is blanketed by Mia Klick, Native and Strong Lifeline coordinator on the left, and Vicki Lowe, executive director of the American Indian Health