U.S. Life Expectancy Drops Amid ‘Disturbing’ Rise In Overdoses And Suicides

BY COLIN DWYER, NPR

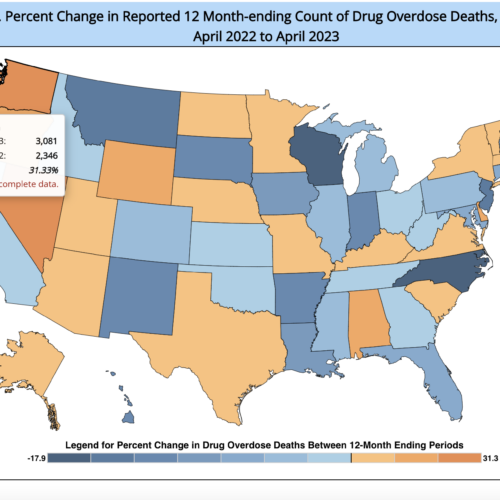

For the second time in three years, life expectancy in the U.S. has ticked downward. In three reports issued Thursday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laid out a series of statistics that revealed some troubling trend lines — including rapidly increasing rates of death from drug overdoses and suicide.

CDC Director Robert Redfield described the data as “troubling.”

“Life expectancy gives us a snapshot of the Nation’s overall health and these sobering statistics are a wakeup call that we are losing too many Americans, too early and too often, to conditions that are preventable,” he said in a statement released Thursday.

Redfield tied the drop in overall life expectancy, which averaged 78.6 years in 2017, a decrease of 0.1 from the year before, to the rise in deaths from overdose and suicide.

More than 70,000 people died of drug overdoses last year alone, according to the CDC. That number marks a nearly 10 percent increase from 2016 and the highest ever in the United States for a single year. By comparison, only about 17,000 people died of overdoses in 1999, the earliest year for which the CDC offered data Thursday.

Recently, that rise has been partly driven by the opioid epidemic and a sharp uptick in the number of deaths involving synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl — a stunning 45 percent leap in the span of a single year, from 2016 to 2017.

“It’s striking to see that there are more people who died of overdose in 2017 than at the peak of the HIV epidemic or the highest rates of traffic fatalities that we’ve seen in this country,” Kathryn McHugh of Harvard Medical School tells NPR’s Richard Harris.

At the same time, suicide rates have also steadily increased, according to the CDC, making it the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. — and the second most common cause of death for people ages 10 to 34. That age range dovetails with the data on drug use, which showed people age 25 to 54 dying at higher rates than their older counterparts.

In other words, younger adults have largely been hit hardest by these trends.

“We’re seeing the drop in life expectancy not because we’re hitting a cap [for lifespans of] people in their 80s. We’re seeing a drop in life expectancy because people are dying in their 20s [and] 30s,” McHugh said.

Now, the reports released by the CDC did not offer only bad news. The data also reflect a declining rate of people dying of cancer, down 2.1 percent from 2016 to 2017.

But in general, says William Dietz of George Washington University, the main themes of the reports are “very disturbing” — partly because deaths from overdoses and suicides are likely linked. Both may be caused by social shifts in the U.S. that have caused people to become “less connected to each other in communities,” he tells Harris.

“There are some data to suggest that that’s led to a sense of hopelessness, which in turn could lead to an increase in rates of suicide and certainly addictive behaviors.”

McHugh, too, sees a link between these two increasingly prevalent causes of death.

“There has been an assumption at times that overdoses fit into one of two categories: they’re intentional or they’re unintentional,” she says. She notes that many people may have suicidal thoughts prior to an overdose or that others may take their lives to escape addiction. “There’s a tremendous amount of overlap between the two that isn’t talked about nearly enough.”

Ultimately, she makes a similar point as the CDC director does: These are causes of death that should be preventable. And while efforts to combat the opioid epidemic “are starting to stem the tide,” she says, “we need to be doing much more.”

“It’s not enough to just try to keep this rate from escalating,” McHugh adds. “We need to start to see this rate going down.”

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit npr.org

Related Stories:

New website to help clinicians in WA prescribe medication for opioid use disorder

Emergency room clinicians across Washington will now have access to a new resource to provide medications for opioid use disorder.

Federal funds to battle opioid addiction coming to rural western Washington hospitals

For people seeking medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorder in some rural Washington communities, there could soon be more options. Recent grant funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has been allocated to develop medication-assisted treatment (MAT) at rural clinics.

How Washington, Idaho are attempting to reduce increased opioid overdose deaths

In downtown Tacoma, Rachel Ahrens said she sees drug use and abuse frequently.

“I’ve personally seen somebody that was just slumped up against the door and looked to be like an overdose,” said Ahrens, who is the building administrator for First United Methodist Church. “I didn’t have Narcan at that time, so I wasn’t able to administer that. So I had to call 911, for them to help the individual.”