A Yakama Woman’s Promise To Her Elders Sheds Light On A Forgotten Northwest War

Listen

Emily Washines was 18 years old when she was crowned Miss National Congress of American Indians. Yakama tribal councilmembers and elders sung a warrior song for her and then extracted a promise.

“After I got a pageant title, [they said] we want to talk to you about who Yakama women are,” Washines said. “I thought, ‘Oh gosh. There is going to come cooking lessons or something.'”

But tribal leaders had something else in mind. They wanted Washines to remember a message about a little-known war that wracked the Pacific Northwest in the 1850s.

“They said Yakama women fought in the Yakama War,” Washines, now 37, recalled. “I remarked immediately, ‘I promised to carry that and to know that and to share that.'”

The impacts of that war still reverberate today. Now Washines is seeking descendants of the federal troops and militia who fought her ancestors more than a century ago. She and they hope to make a statement about healing, dialogue and remembrance by coming together.

In her 20s, Washines married, had three kids and started a culture and history blog. Then, in her mid-30s, she returned to the promise. Washines got an artist development grant from The Evergreen State College and made a video narrated mostly in Ichiskiin (also known as Sahaptin language) about the Yakama War.

But there was a hitch. Washines couldn’t find records of what her elders told her from the U.S. Army side.

So she decided to reach out to historic enemies.

“I thought maybe I’ll go and ask the descendants if they have journaled about it or know about it, or if they would consider standing by my side while I at least tell that history and account,” Washines said in a recent interview.

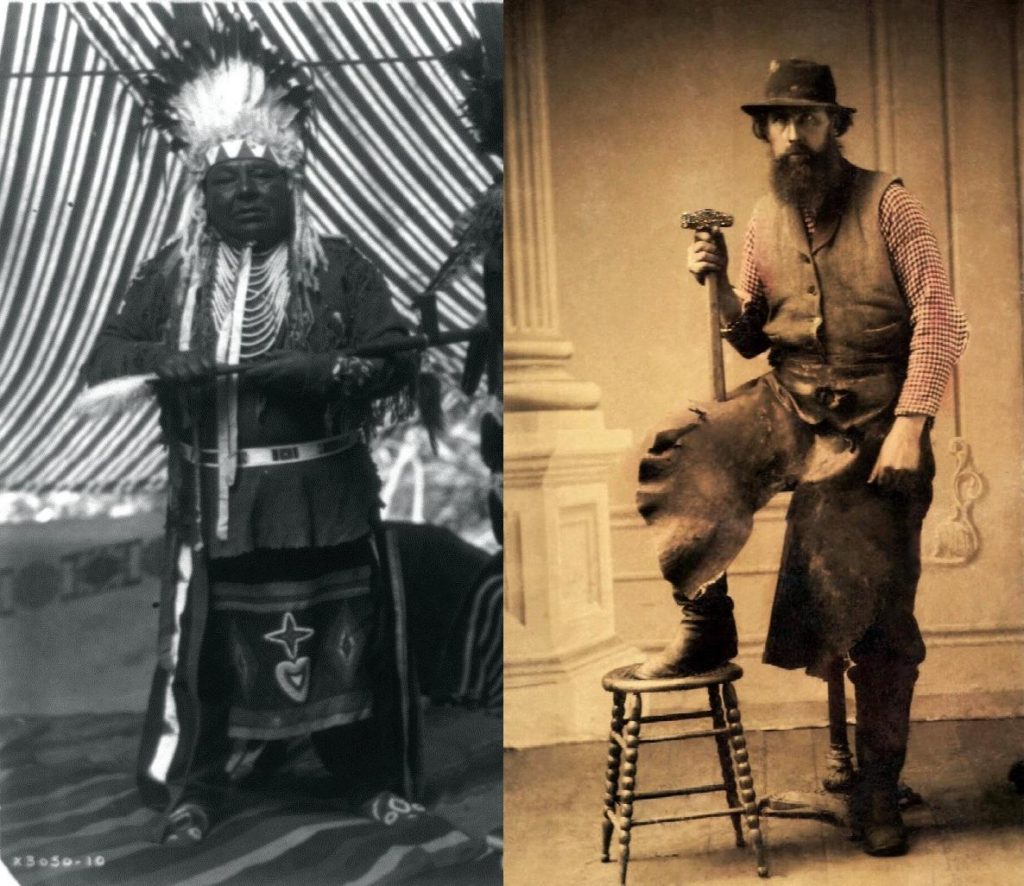

George Meninick (left) and Supplina Hamilton were on opposite sides of the Yakama War when they were younger than shown here. Glen Hamilton is a descendant of Pvt. Hamilton and Emily Washines can trace her lineage to future Chief Meninick. CREDIT EDWARD S. CURTIS COLLECTION, 1910. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / COURTESY OF FAMILY OF GLEN HAMILTON; 1860-70S

Since putting the word out, Washines has gotten in touch with eight descendants of those who fought her ancestors. Glen Hamilton, a digital marketing director who lives in Everett, Washington, is one of them.

“Growing up I knew that I had a great-great grandfather — my grandfather’s grandfather — who had been an ‘Indian fighter’ and came west as a young man from Illinois,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton was already researching his family genealogy to learn more when he heard a story on public radio in August 2017 about Washines and her quest. Hamilton’s ancestor, Pvt. Supplina Hamilton, was a blacksmith in Linn County, Oregon, when the territorial governor issued an urgent call in the fall of 1855 for volunteers to put down an Indian rebellion.

Washines can trace her lineage back to a Yakama chief who fought in the war when he was a teenager.

The roots of the Yakama War resemble many others between Native Americans, settlers and the U.S. Army in the 19th-century American West.

Inland Northwest tribes and bands signed a treaty with the U.S. government: the Treaty of 1855. But a short time later, miners and settlers trespassed on reserved lands, some committing rapes and murder. That prompted reprisals and ambushes. Cavalry marches and cannon bombardments spilled over into Oregon and Western Washington, and tribes attacked the new settlement of Seattle.

Skirmishes and fighting lasted until 1858 when an Army general imposed a peace treaty and forced most tribes onto reservations.

Washines said the war history still evokes raw feelings among Native people.

“It shocks a lot of people to know that I am studying the Yakama War and putting this out there,” she said. “There is still a lot of hurt there. It’s a very hard history to hear.”

That history extends into the present day for non-Natives, too. Washines recalled an incident from midsummer that involved two EMTs who worked for a private ambulance company that responds to emergencies in the Yakima Valley, including on the Yakama reservation. American Medical Response fired the two men after they posted racist and derogatory comments on Facebook. One of the EMTs accused Native Americans of being poor losers and expressed a desire to “finish the job” of conquering them.

Glen Hamilton, the ‘Indian fighter’ descendant who first corresponded with Washines by email, stressed how little the public knows about the war in the Pacific Northwest’s past.

“One-hundred sixty-three years ago there was a major military conflict that happened here in our state,” Hamilton said. “And we don’t even know about it.”

Hamilton and Washines met in person this fall at historic Fort Simcoe on the Yakama reservation. They met again when Washines lectured about her project at the Seattle Public Library earlier this November.

The first descendant from the U.S. Army side that Emily Washines met was author Steve Plucker of Prescott, Wash. Plucker identified himself as the great-grandson of Pvt. Charles Plucker who fought in the Yakama War. COURTESY OF EMILY WASHINES

Washines acknowledged Hamilton in the audience and then invited him to pose on stage together with her. People in the audience pulled out cameras and cell phones to snap a picture of the two.

“These are descendants of the Yakama War standing side by side,” Washines told the crowd. “It is not an ‘us versus them’ story anymore.”

Hamilton said that his experience with Washines has had a ripple effect.

“This whole journey with [Washines] and the work that she has begun in bringing together descendants of this very brutal and violent conflict to stand side by side and to remember — and to be able to just look at the truths and have empathy and want to move forward together — it’s had an impact across my entire family,” he said.

Both Hamilton and Washines continue to research the Yakama War. Sometimes, they work together.

Hamilton and Washines have a shared near-term goal to get a retraction from the Yakima newspaper of a 1904 article that inaccurately explained how the war started. Washines is also still hunting for evidence that could corroborate the oral history within her tribe about female warriors who fought against the U.S. Army.

And Washines still remains interested in connecting with descendants of ‘Indian fighters’ — particularly descendants of Maj. Granville Haller. Haller commanded a company of around 100 infantrymen and militia who marched from Fort Dalles, Oregon, to the first engagement of the Yakama War in October 1855.

Haller was outnumbered and defeated when he encountered Chief Kamiakin of the Yakamas who led a much larger force, possibly more than 1,000 strong.

Haller later commanded Union forces in the Civil War and afterwards returned to the Pacific Northwest to become a successful businessman. He was buried in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery in 1897.

Early this month, the historic preservation nonprofit Historic Whidbey purchased the house Haller built in 1866 in Coupeville and plans to restore it. Haller House is one of the oldest surviving homes from Washington Territory days. Haller Lake in North Seattle is named after the Army leader’s son.

Washines said she is in touch with Historic Whidbey about helping them to flesh out Haller’s legacy in the Northwest.

Related Stories:

Fish hatchery transferred to Yakama Nation, upgrades underway

Yakama Nation tribal members fish in the Klickitat River for fall chinook salmon. The Yakama Nation recently gained ownership of a fish hatchery on the river. (Credit: USFWS – Pacific

Hanford safety officer hired on by Yakama Nation

Rattlesnake Mountain on the Hanford site in 2022. The mountain is sacred to the Yakama Nation and other Northwest Indigenous tribes and bands near the Hanford site. (Credit: Anna King

Yakama Nation, city of Toppenish in court battle over warming center

A water tower in Toppenish, Washington. The Yakama Nation is suing the city of Toppenish to be able to run a 24-hour warming shelter in the city on reservation land.