BOOK REVIEW: ‘Death And Other Holidays’ Is A Perfect Literary Break

BY LILY MEYER

Consider the novella. It’s a tricky form. Too short, some might say, or too long, or — what is a novella, exactly? A big story? A small book? Maybe you’ve read Ian McEwan’s declaration that the novella “lays on the writer a duty of unity and the pursuit of perfection,” or Taylor Antrim’s claim that it’s “fiction’s most open-ended and compellingly discursive form.” If you have, forget it. Let’s start fresh.

Novellas are the ice-cream sundaes of literature. Not a whole meal, unreasonably large, messy, overflowing, unnecessary — and, for those reasons, rare and total delights. Novellas are too short to bog themselves down, but long enough for some truly satisfying twists and turns. Long enough, for example, to narrate a full year in a character’s life, and to let the reader watch her life change.

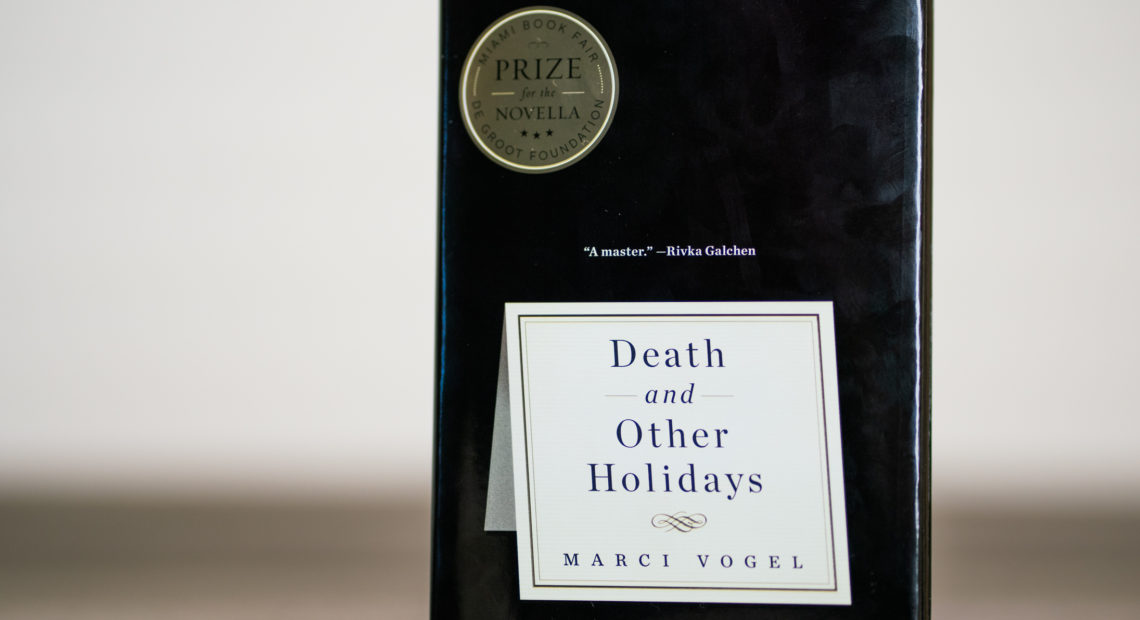

Death and Other Holidays, poet and translator Marci Vogel’s fiction debut, does exactly that. Vogel won the 2017 Miami Book Fair/de Groot Prize, which is America’s only book award honoring the novella, and it’s a thrill to see that award — any award — given to writing as shaggy, conversational, and unabashedly poetic as hers. She writes in tiny chapters, a few paragraphs or pages long, moving her story forward not in events but in snapshots. The story here is simple: April, the twenty-something protagonist, starts the novella grieving an unlikely pair of losses. By the end, she’s reconciled her grief.

The first loss is that of her stepfather, Wilson. In a chapter called “Patrimony,” April, who is appealingly, perennially blunt, explains, “I used to have two fathers, but now I have none. The first death was intended, he used a belt. The second one, Wilson, it was an accident of cells.” Wilson adored April, and April adored him back. His dying instructions to her were, “Your life is just beginning,” and a note reading START, GO. But April can’t start. It’s spring and the world around her is blooming, but she’s floundering, trapped in her grief.

Meanwhile, her best friend Libby is zooming forward. Libby is a planner, both professionally — she works at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power — and spiritually. “Libby’s measure of truth can be exacting,” April explains, “but once she’s a friend, it’s forever.” Forever, sure, but Libby’s engaged to a man named Hugo and moving from the apartment she shared with April shared to a fixer-upper in the Valley, leaving April with a terribly laid-out one-bedroom and, as Ariel Levy wrote of the film Walking and Talking, “the sense of abandonment that you feel when an intimate pushes ahead in life without you.”

Death and Other Holidays‘ friendship arc is reminiscent both of Walking and Talking and Noah Baumbach’s more recent Frances Ha. Libby charges ahead, and April stays sadly in place, coming home early from Libby’s Fourth of July party and watching “reruns of I Love Lucy to keep myself from dissolving.”

Vogel splits the novella into seasons, and in Spring and Summer, April seems ready to dissolve. She misses both her fathers. She misses Libby. Then, on the first day of Fall, she’s developing pictures from Libby’s party and begins wondering “how I could have been right there and have missed so much, in my mind, I mean, not the actual shot.” What she missed, it turns out, is Hugo’s cousin Victor, “sitting over the pool, cross-legged atop the diving board … in a halo of sparklers.”

In a short story, April and Victor would have sex once, and that would be that. In a novel, they would hit some kind of horrifying roadblock. In a novella, they get to fall in love. They garden together, tell secrets, ease into each other’s routines. It’s life-charming, not movie-charming. It’s as real a depiction of falling in love as you can read.

Vogel is a poet, and though she never lets her plot get poetic, her language moves entrancingly between high and low. Bathing his ancient chocolate Lab, Argos, Victor asks softly, “Where’s all the brown going to come from, Argos? Leather and wood and chocolate? Will there be any left when you’re gone?” The line is at home among descriptions of the 110 freeway, a bridal shop called Cupid’s Playground, brutal one-line character sketches like “Math Man, tall with a good job, half a dozen blue chamois shirts out of the J. Crew catalogue, and a no-girlfriend policy.”

Death and Other Holidays brilliantly balances humor and anger, sorrow and beauty. Vogel’s subjects may be grief and death, but her writing reflects life as we live it, life with its many intricate, unnoticed balances. When the novella ends, it’s spring again. A year has passed. It’s time for April and Victor to follow Wilson’s instructions. They’re ready to START, GO.

Lily Meyer is a writer and translator living in Washington, D.C.