Finding Inspiration Amidst Chaos: Classical Music Of The First World War

Read On

This month (Nov. 11, to be precise) marks the centennial of the end of World War I, otherwise known as the “Great War” and the “War to End All Wars.” Simply put, it was a cataclysm, a conflict that marked a threshold in modern history. In the world of classical music, composers responded in many different ways.

Even as the war was beginning in July 1914, Englishman Gustav Holst was sketching the ominous first section of his large-scale orchestral suite, “The Planets.” British audiences had never heard such musical ferocity as confronted them in “Mars, the Bringer of War.” Holst’s countryman Ralph Vaughan Williams took a contrasting approach. In writing his Third Symphony (“A Pastoral Symphony”), he incorporated a haunting passage for solo trumpet in the slow movement, inspired by the sound of a bugler practicing at sunset. The composer described the scene, located near the front lines in France, as “Corot-like,” a reference to the acclaimed 19th century French landscape artist, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. (Vaughan Williams served as an ambulance driver during the war.)

The Danish composer Carl Nielsen made a compelling case for the value of art and humanity over conflict and destruction, the “elemental will to live,” as he put it, in his own Fourth Symphony, subtitled “The Inextinguishable” (1914-16). In its final pages, a beautiful and lyrical theme from the first movement returns, rising above two warring sets of timpani.

Charles Ives, that often rambunctious American composer, wrote one of his most heartfelt pieces during the war. In response to the entry of American forces into the conflict, he set verses by Canadian physician and military officer Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae. Ives’ haunting song, “In Flanders Fields,” received its premiere at a luncheon for insurance executives (including the composer himself) at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York in April 1917. In that very same month, Scott Joplin, often cited as the “father of ragtime,” passed away in New York. Alas, ragtime effectively died with him.

Maurice Ravel, who would later give the world “Bolero,” honored friends and colleagues who had died in the war with his suite called “Le Tombeau de Couperin” (1914-17). It emulates a Baroque era sequence of dances. When asked why the pieces failed to express tragedy, several are downright cheerful, the composer responded, “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”

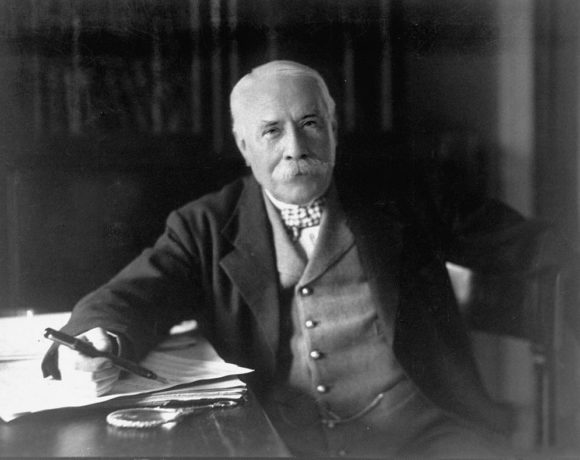

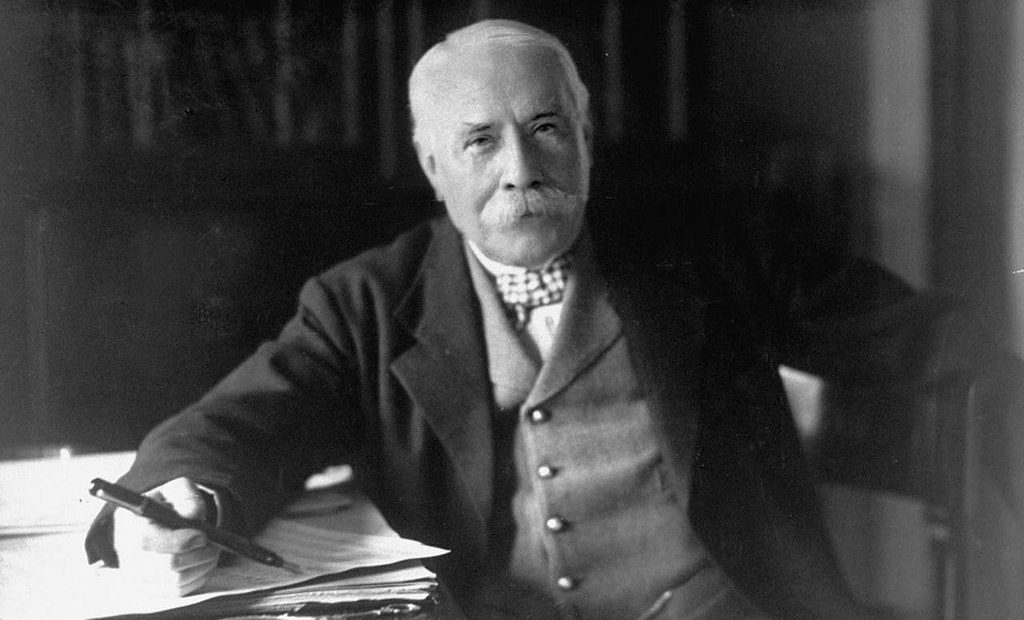

World War I officially ended at 11 a.m. Nov. 11, 1918. Perhaps no classical musician responded more poignantly to its horrors than Edward Elgar. The English composer, who had previously written such assertive music as his Pomp and Circumstance marches and two symphonies, sounded an elegiac, brooding and melancholy note in his magnificent Cello Concerto (1919). In it, he sadly reflects on the “undercurrent of our failings and sorrows” and offers a “lament for a lost world,” to quote him.

Even as our contemporary world marks the 100th anniversary of the war’s end, the wealth of music it prompted speaks as profoundly as ever.

Copyright 2018 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Maria

“Maria Callas was someone that as she was singing, she was dying every time. Life was taken from her while she sang.” The Chilean writer-director Pablo Larrain has a fascination with mortality. The manifestations of it course throughout his work. In many respects, it inspires his art.