Horror Older Than America: Whitewashing Native Tales For A Mass-Market Audience

Read On

In the beginning, according to the Nez Perce creation story, there was a monster. The story says that Coyote (Iceye’ye) killed the monster because it was eating all the other animals.

After forcing the monster to inhale him, Coyote cut the monster apart from the inside, throwing parts of its body across the land and therefore creating the new peoples of the continent.

Mid-task, Fox asked Coyote why he had flung the largest parts of the monster away, leaving nothing left to form a new people in the land where he stood. Coyote washed his bloody hands and shook them upon the earth. The mixture of water and blood formed the Nez Perce.

The remaining chunk of the monster, according to the story, rests near Kamiah, Idaho, at Heart of the Monster in Nez Perce National Historical Park.

The heart of the monster that Iceye-ye killed can still be seen near Kamiah, Idaho today. CREDIT: NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Tales of otherworldly beasts tend to come to the forefront during October. But just as trick-or-treaters need to watch out for costumes that insensitively appropriate other cultures, storytellers also need to be mindful of whitewashing traditional narratives.

“Monster stories may hold very different associations in Native stories,” said Tiffany Midge, a Moscow, Idaho, poet and Standing Rock Sioux member. “In some traditions, the different monsters are deities. But there’s certainly a great many so-called ‘horror’ elements to a great many different Native legends. But imposing Western interpretations on them flattens and diminishes them to some extent.”

The most used Native trope in horror is the idea of houses or entire cities being built on an “ancient Indian burial ground.” “The Amityville Horror,” perhaps the most famous ghost story in America, uses this idea. Essentially, these are tales of white settlers ravaging the sacred lands of the indigenous people and building their homes over the bodies of Native dead. The ground turns from sacred to cursed and whomever inhabits the land will also be cursed.

“Imposing Western interpretations on (Native cultures and traditions) flattens and diminishes them to some extent. That’s the hazard, anyway. And, of course, that’s what these movies are doing, as well,” Midge said.

The “Indian burial ground” trope is wide-ranging and became more abundant during the horror boom of the late 1970s and ’80s. Stephen King, America’s most well-known horror writer, used the cliché in “The Shining” and in “Pet Sematary.” Even Sunnydale, home of vampire slayer Buffy Summers, was built on land sacred to Native people. A true sign of cultural saturation, a curse home built on sacred Native graves also turned up in a Treehouse of Horror episode on “The Simpsons.”

Perhaps the most egregious use of this idea comes from the “Poltergeist” franchise. In the first film, we learn that the suburban California home of the Freeling family was built over a cemetery. “You moved the headstones, but not the bodies!” Steven Freeling (played by Craig T. Nelson) yells near the end of the film.

Things get worse in the second film when it is revealed that not only was the home built over a cemetery, but that cemetery had been placed over a cavern that was home to a religious cult and possible a Native burial site before that.

“It’s a trope that needs to be ‘laid to rest,’ so to speak,” said Midge. “But I guess it’s serving as a cautionary tale to Western expansion and colonialism.”

“Poltergeist II” does something that mainstream horror films using the burial ground cliché hadn’t done before: allow a Native character to actively fight against the presentation of evil in the film. Taylor (Will Sampson) a Native shaman who provides Steven Freeling with the spiritual weapons to combat the evil plaguing the family.

Even King, perhaps the most mainstream writer of horror fiction, used the desecration of sacred lands and the subsequent burial ground cliché as the site of the Overlook Hotel in “The Shining” and as the place Louis Creed buries his son Gage in “Pet Sematary” but in the later book, King added another Native-based aspect: the Wendigo.

Wendigo stories appear in several places throughout North America and are often warnings against cannibalism. In some stories, the Wendigo is even responsible for wiping out the Donner party in 1846 as the were stranded in the Sierra Nevada mountains and resorted to eating the flesh of their dead.

The relationship between flesh-eating monsters and Natives has recently taken on a new aspect. In comparing attitudes seen in the show “The Walking Dead” and attitudes toward the Native experience, scholar Cutcha Risling Baldy asked the question “can we come back from this?” in her 2014 article “Why I Teach ‘The Walking Dead’ in My Native Studies Class.”

She compares the zombie apocalypse scenario to the real-world realities faced by indigenous people during the California Gold Rush and “Indian hunting” sessions.

“What those who survived experienced was both the ‘apocalypse’ and ‘post apocalypse.’ It was nothing short of zombies running around trying to kill them,” she wrote.

Like the zombie hordes of “The Walking Dead,” Risling Baldy points out that the people trying to kill Natives and desecrate their lands weren’t necessarily strangers.

“The atrocities of genocide during this period of time were not committed by monsters — they were committed by people. By neighbors. By fathers, sons, mothers, and daughters,” Risling Baldy wrote.

Risling Baldy is one of a handful of Native scholars and artists approaching the horror genre. Writers such as Stephen Graham Jones and Owl Goingback are from Native backgrounds and have used the stories to influence their work. While not a horror writer, Midge also has an interest in the genre.

“I can’t 100 percent say that these movies are based on any actual stories originating in Native communities,” Midge said, “but they totally capture a lot of the general idea with regards to ghosts, visitations.”

Midge cites the films “Imprint” and “Older Than America” as Native-driven and produced films that deal not only with horror tropes but also the realities of Native issues such as life on reservations and the history of boarding school traumas. Knowing how these stories entered Western thought and then into the tales of horror is important, too.

“If you visit the Smithsonian American Indian Museum, there’s a room of moccasins on display. They’re art, beauty, celebratory relics from the 19th century. Where’d they originate, though?” Midge said. “I see it as funeral and objects of genocide. But of course they’re not displayed as such.”

Comparing the atrocities and monsters of different people and times remains a complicated topic, Midge said.

“And then if one visits the Holocaust Museum in D.C., there’s this huge plexiglass box structure full of shoes taken from the concentration camps. That message is 100 percent clear,” Midge said. “It’s such a disparate portrait, isn’t it?”

Copyright 2018 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

‘It just tastes like time’: Salmon are a sacred relative to the Nisqually tribe and Native Americans across the Northwest

Freshly caught chum salmon display their greens and pink colors like the aurora, in December on the Nisqually River. (Courtesy: Willie Frank III) Listen (Runtime 3:54) Read On a tall

‘Fish War’ screens in Wenatchee

“Fish War” screens at the Numerica Performing Arts Center on Thursday. (Credit: North Forty Productions) Listen (Runtime 0:56) Read WENATCHEE— A documentary highlighting tribal leaders who stepped forward as environmental

Washington state bill could change how rural communities could work to close a library

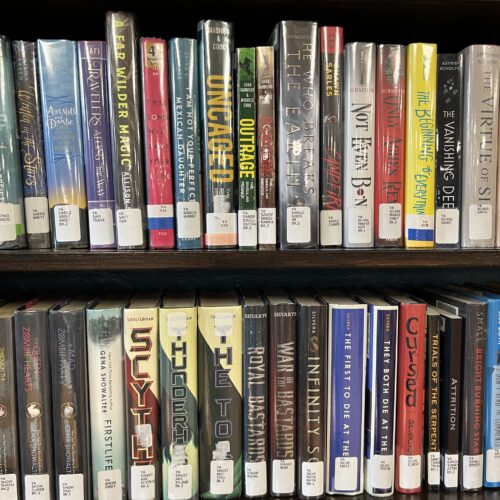

Young adult books at the Columbia County Library. Some people have requested to move the YA section into the adult section because of what they call “obscene” material in 100