Sainthood Comes For Archbishop Oscar Romero, Assassinated ‘Voice For The Voiceless’

Listen

In March 1980, Patricia Morales Tijerino and her sister had just left a wedding in a little chapel in El Salvador’s capital and were on their way to the reception.

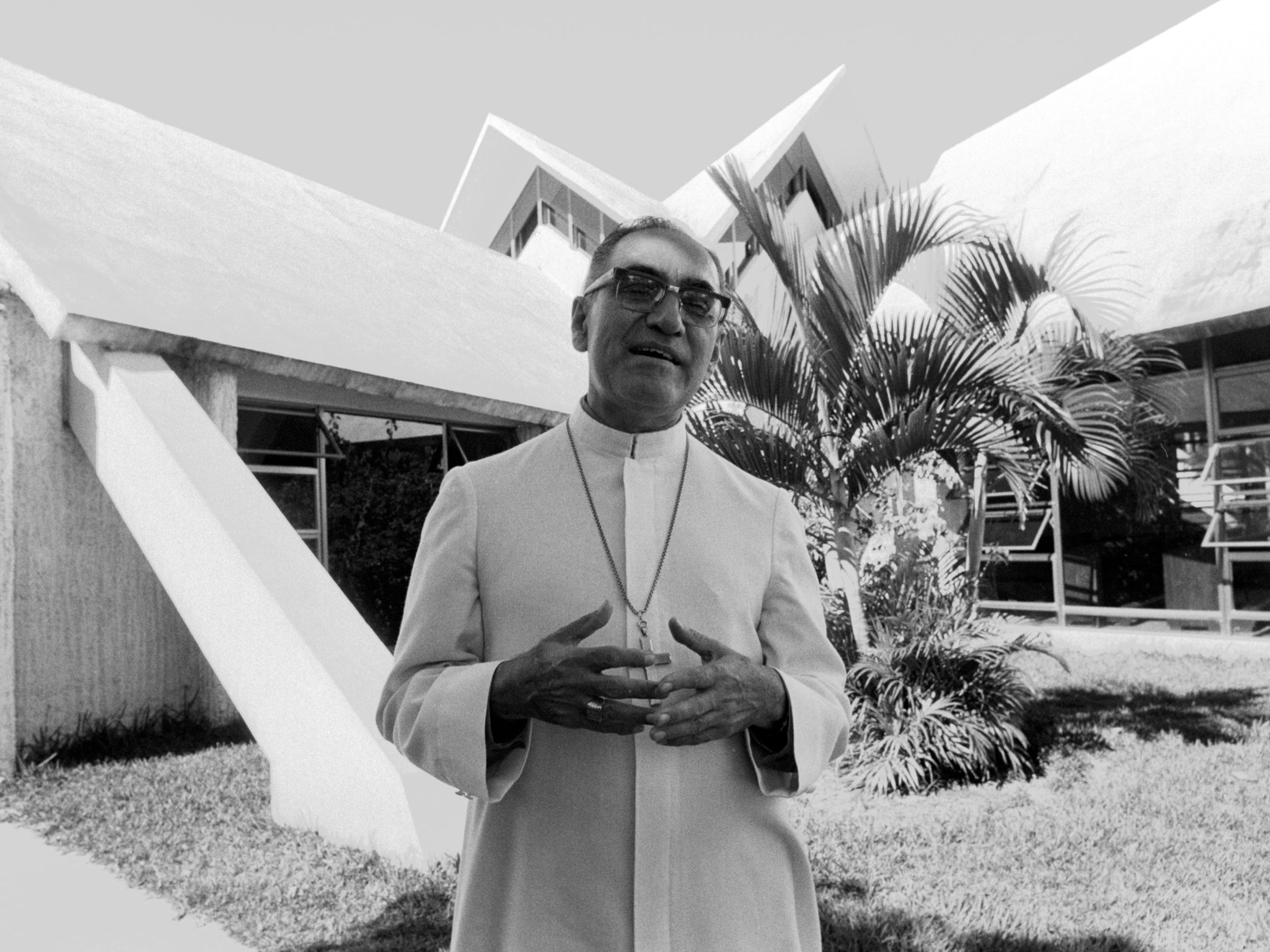

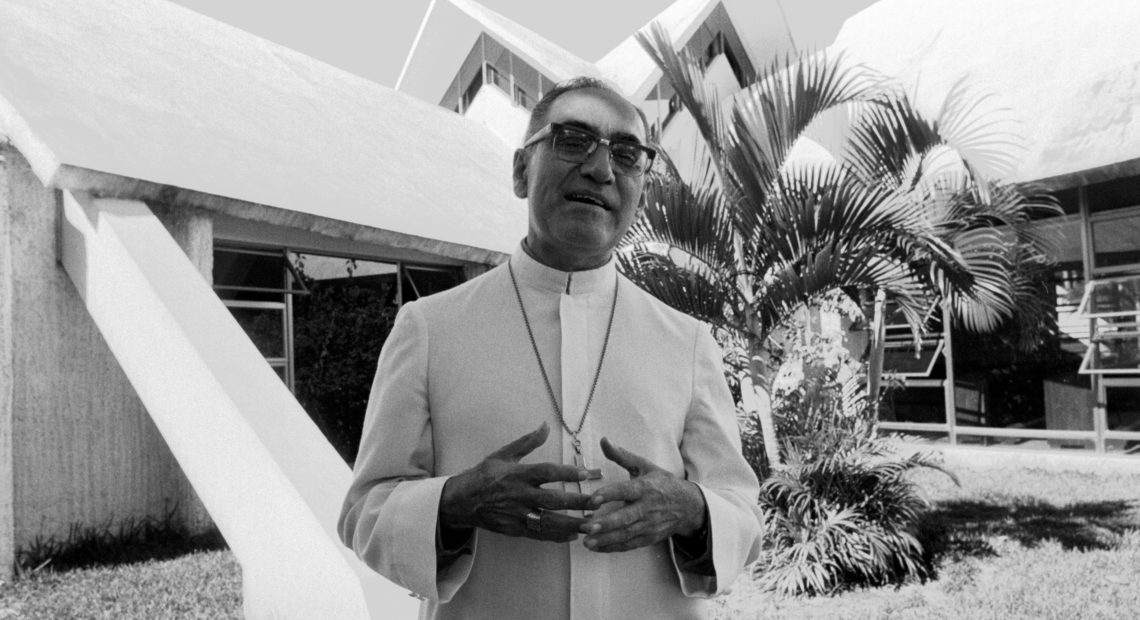

“And then I spotted him,” Morales Tijerino recalls. “He was in his white cassock.”

Óscar Arnulfo Romero, the Roman Catholic archbishop of San Salvador, was standing alone in a garden outside the church.

“We were his admirers and his followers and we had never met him before,” Morales Tijerino, now 55, says. “So we approached him, right? We’re two teenagers, just to say ‘hello’ and ‘how are you?’ And he was very soft-spoken. He said, ‘Preocupado,’ which means worried. ‘Preocupado.’ “

Two days later, Romero was dead, gunned down by members of a right-wing death squad.

A Messenger Of Hope

On Sunday, Oct. 13, 38 years after his assassination, Romero will be canonized as a Catholic saint. Known to his followers as Monseñor (Monsignor), Romero was a champion of human rights at a time when El Salvador was on the brink of civil war. His tireless fight for civil rights ranks him among figures like Martin Luther King Jr. His devout following filled San Salvador’s towering cathedral each Mass.

Two days later, Romero was dead, gunned down by members of a right-wing death squad.

This Sunday, 38 years after his assassination, Romero will be canonized as a Catholic saint. Known to his followers as Monseñor (Monsignor), Romero was a champion of human rights at a time when El Salvador was on the brink of civil war. His tireless fight for civil rights ranks him among figures like Martin Luther King Jr. His devout following filled San Salvador’s towering cathedral each Mass.

At that time, “Hope was like water in the desert,” Duran says. “It was scary to live in those days.”

People crowd into San Salvador’s Metropolitan Cathedral to listen to a sermon by Romero on Sunday, May 27, 1979. CREDIT: P.W. Hamilton/AP

In the late 1970s, civil war loomed. Decades of government oppression sparked massive protests. Peasant workers united in the countryside, demanding basic rights. Popular opposition groups and teachers’ unions called for wealth distribution, while leftist guerrillas took up arms against the military and government elites.

In rural Catholic churches, some priests and nuns supported the peaceful cause on behalf of the poor. But they were up against El Salvador’s corrupt oligarchy. The country’s so-called “Fourteen Families,” who controlled most of the land and wealth, accused the priests and peasants of a communist uprising.

The Salvadoran National Guard roamed streets, searching for subversives. Priests were expelled from the country, beaten and imprisoned. Security forces burned villages and committed rape. The National Guard arrested family members, who never returned home again.

El Salvador’s brutal military regime — supported by the United States — kidnapped, tortured and killed civilians, many of them among the poorest.

The ‘Voice For The Voiceless’

“These were atrocities towards innocent people, young people, even children,” says Morales Tijerino, who is an interpreter, translator and human rights activist. She says Romero defended the most vulnerable.

“The people felt protected by him,” Morales Tijerino says. “That protection was the power of his words.”

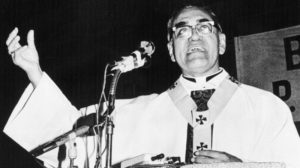

Romero ran a church commission that investigated human rights abuses, and he openly denounced the violence of leftist and rightist forces alike. During Mass, he named victims of murder and those who disappeared. State-run media weren’t reporting on the institutionalized violence, so Romero’s homilies turned into newscasts for the poor. His message inspired the repressed and his words gave them their dignity.

“He became the voice of the voiceless,” Morales Tijerino says.

The day before he was murdered, Romero pleaded with members of the military to disobey orders to kill.

“At a time of so much confusion and anguish,” Romero said in a 1980 homily, “I want to be a messenger of hope. In the midst of tragedy and bloodshed, there is hope.” CREDIT:

Bettmann Archive

“In the name of this suffering people, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression,” Romero declared, to thunderous applause.

“Be A Patriot, Kill A Priest”

Romero was a polarizing figure in Central America — family members often disagreed among themselves over his support of the poor.

“Part of my family believed that he was taking away from the rich. Others saw him as a communist, meddling in politics,” says Sister Ana María Pineda, author of Romero & Grande: Companions On The Journey, a biography of Romero and his friend, Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande. “The other side of my family loves Romero. And so we reflect the mixed reality of El Salvador.”

Romero was especially divisive within the Catholic Church in El Salvador. Some of his fellow bishops, loyal to the government, called him a subversive and accused him of inciting violence among the peasant class.

“That was a very painful reality for him,” Pineda says.

In private, Romero seemed isolated.

“He had a bad temper, he was an introvert, he preferred to be alone and he was a perfectionist,” Pineda says. “For all of his life, he struggled.”

He was also uncompromising, Ricardo Urioste, Romero’s vicar general and friend, recalled. In a book published in 2000, Monseñor Romero: Memories In Mosaic, Urioste is quoted saying: “When [Romero] had his mind made up about something, he was relentless — really stubborn. Like a steamroller.”

But, Duran says, “He was such a good person, he had a good heart.”

Leftist demonstrators flee after Salvadoran National Guard troops fire into a crowd of protesters on the steps of the San Salvador Cathedral on May 9, 1979.

CREDIT: Tony Comiti/Sygma via Getty Images

He remembers how Romero suffered through bouts of anxiety and depression. “Even though he was that shy person, when he spoke at the pulpit, he was a giant.”

In Romero’s war on inequality, the transistor radio was his weapon. Live broadcasts of his homilies on YSAX, El Salvador’s Catholic radio station, became the most popular program in the country, according to the book El Salvador: The Face of Revolution.

“On Sunday, every house had their radio on,” Morales Tijerino recalls. “If someone was walking from one end of the neighborhood to the other, they wouldn’t miss a moment of his homily.”

“Listening to Monseñor Romero was prohibited by the army. But everybody — everybody — was listening,” Duran says. “Including his enemies.”

Priests and nuns who advocated for and supported the poor were targets. Right-wing militants bombed the YSAX radio station in February 1980, and fliers showed up outside of churches with the message: “Be a patriot, kill a priest.”

“I received notice that I’m on the list of those who are to be eliminated next week,” Romero told his congregation one month before his murder. “But let it be known that no one can any longer kill the voice of justice.”

Assassination Of A Priest

“I was so close to him, we were friends,” says José Inocencio “Chencho” Alas, a former priest in El Salvador. The last time he saw Romero, Alas sensed that his friend was afraid.

“There was a moment that he said to me, ‘Chencho, they want to kill me. But I must stay with my people.’ He was offering his life.”

A nun clasps her hands in prayer as others gather around Romero after he was shot at the altar while celebrating Mass in 1980. CREDIT:

AP

On March 24, 1980, Romero was celebrating Mass with a small gathering at the chapel of the Hospital de la Divina Providencia in San Salvador. A gunman from a right-wing death squad shot him as he stood at the altar.

Romero was 62.

“When you talk to Salvadorans of my generation about that day, people remember exactly what they were doing when they heard the news,” Morales Tijerino says. “It was this feeling of losing someone that is yours, of feeling orphaned.”

Romero’s assassination accelerated the conflict in El Salvador. Violence erupted at his funeral and the country soon spiraled into civil war. The U.S. backed the anti-communist military regime. The fighting lasted 12 years, ending in 1992 after claiming over 75,000 lives. Half a million Salvadorans were displaced, and many fled as refugees to the U.S.

Romero’s voice was never silenced. For his followers throughout the world, he became a saint the moment he was shot at the altar.

“With Monseñor Romero, Jesus passed through El Salvador,” Duran says.

But the wounds of war have not healed. Today, El Salvador has one of the highest murder rates in the world. Street gangs — primarily the 18th Street gang and the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) — control sections of cities.

His old friend Alas prays to Romero now for a country that is free of bloodshed:

“Archbishop Romero: We need your voice in El Salvador. Your work has not ended. Please, from heaven, help us. Please.”

In the audio version of this story, poet William Archila provides the English voice-over for Óscar Romero. Archila was born in Santa Ana, El Salvador, and fled to the United States in 1980 during the civil war.

Related Stories:

These churches offer shelter and sanctuary to vulnerable migrants. Here’s why

Bishop Joseph Tyson (left) and the Rev. Jesús Mariscal (right) of the Yakima Diocese worry about how their parishioners will cope with broad changes to immigration policy, which have had

Unpacking the intersection of health care and religion

Religion can sometimes impact health care access in places like Washington and Idaho. (Credit: Joe Raedle / Getty Images) Listen (Runtime 3:22) Read Phineas Pope: Tracy Simmons is the executive

Religious freedom vs. health care access: How faith influences health care in Washington and Idaho

Religion can sometimes impact health care access in places like Washington and Idaho. (Credit: Unsplash / Hush Jade Photography) Read By Emma Maple | FāVS News The Idaho state Legislature