IDs Of Many Native Americans Won’t Be Accepted At North Dakota Polling Places

BY CAMILA DOMONOSKE, NPR

Native American groups in North Dakota are scrambling to help members acquire new addresses, and new IDs, in the few weeks remaining before Election Day — the only way that some residents will be able to vote.

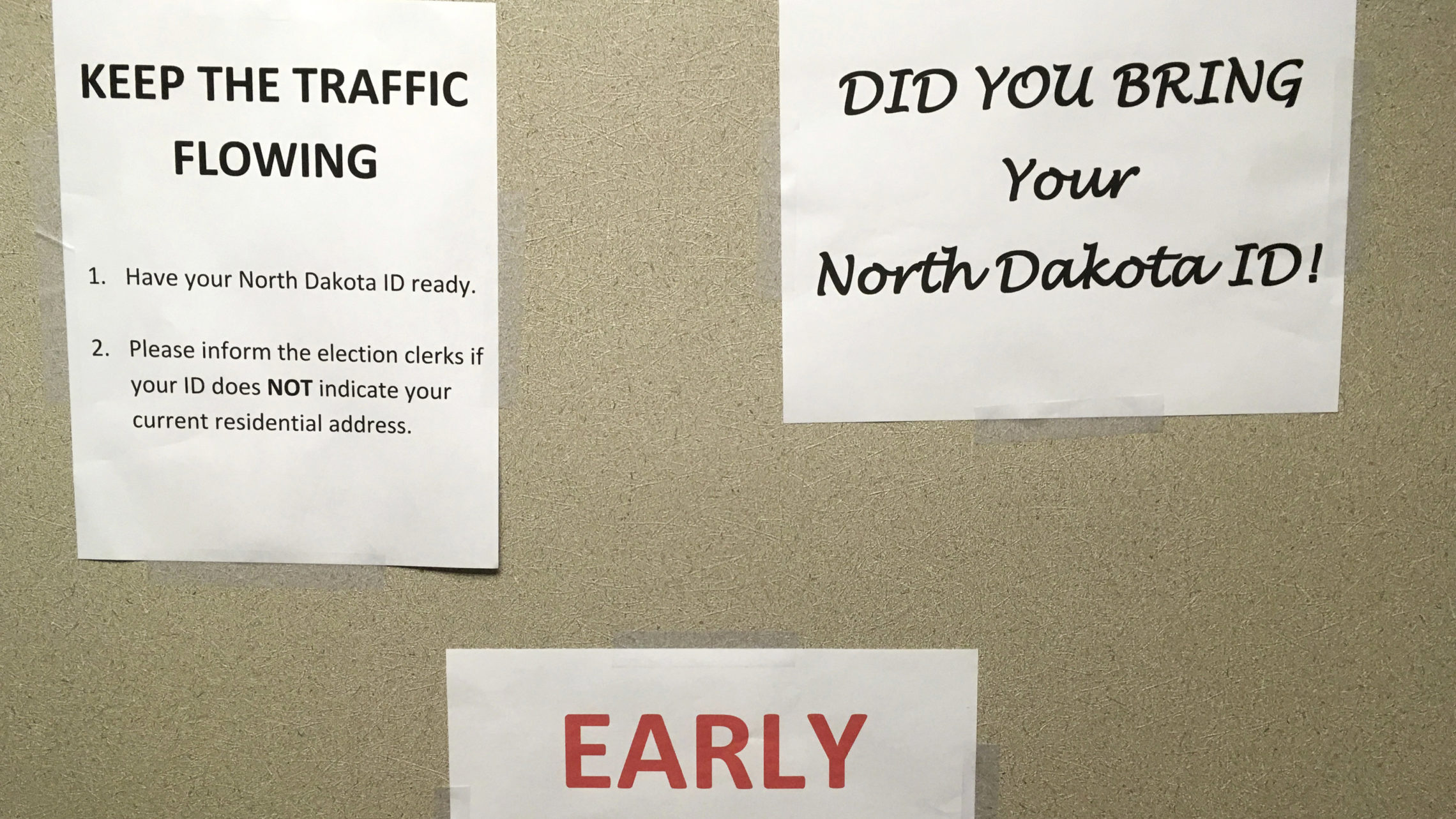

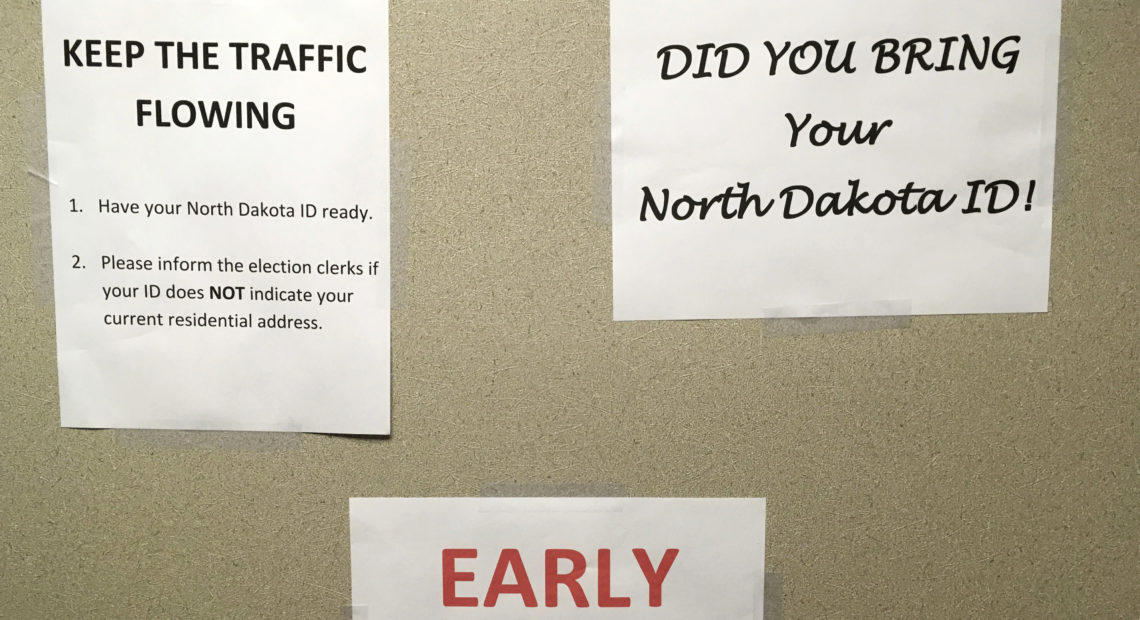

This week, the Supreme Court declined to overturn North Dakota’s controversial voter ID law, which requires residents to show identification with a current street address. A P.O. box does not qualify.

Many Native American reservations, however, do not use physical street addresses. Native Americans are also overrepresented in the homeless population, according to the Urban Institute. As a result, Native residents often use P.O. boxes for their mailing addresses and may rely on tribal identification that doesn’t list an address.

Those IDs used to be accepted at polling places — including in this year’s primary election — but will not be valid for the general election. And that decision became final less than a month before Election Day, after years of confusing court battles and alterations to the requirements.

Tens of thousands of North Dakotans, including Native and non-Native residents, do not have residential addresses on their IDs and will now find it harder to vote.

They will have the option of proving their residency with “supplemental documentation,” like utility bills, but according to court records, about 18,000 North Dakotans don’t have those documents, either.

And in North Dakota, every resident is eligible to vote without advance voter registration — so people might not discover the problem until they show up to cast their ballot.

North Dakota Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, a Democrat, is trailing her Republican opponent in her race for re-election. Native Americans tend to vote for Democrats.

The Republican-controlled state government says the voter ID requirement is necessary to connect voters with the correct ballot and to prevent non-North Dakotans from signing up for North Dakota P.O. boxes and traveling to the state to vote fraudulently. In 2016, a judge overturning the law noted that voter fraud in North Dakota is “virtually non-existent.”

The state government says that residents without a street ID should contact their county’s 911 coordinator to sign up for a free street address and request a letter confirming that address.

A group called Native Vote ND has been sharing those official instructions on Facebook.

Jamie Azure, the tribal chairman of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, says his tribe has been preparing for this shift ever since the law was first passed years ago — but with the final decision coming just weeks before Election Day, “the timing is horrible,” he tells NPR. “It’s just a daunting process.”

The ID requirement change doesn’t just affect the state and federal elections — it’s also affecting Turtle Mountain’s tribal elections, because the tribe follows state and federal voting requirements.

Azure’s tribe is offering free tribal ID days, when residents can get updated IDs with residential addresses at no charge.

“We’re trying to tear down the barriers on our side, at the cost of the tribe,” he says.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is telling members to get in touch if they need help obtaining a residential address and updating their tribal ID. The tribe also says it will be sending drivers to take voters to the polls on Election Day.

“Native Americans can live on the reservations without an address. They’re living in accordance with the law and treaties, but now all of a sudden they can’t vote,” Standing Rock chairman Mike Faith said in a statement. “Our voices should be heard, and they should be heard fairly at the polls just like all other Americans.”

Meanwhile, The Bismarck Tribune reports that a Native American organization is working to come up with a last-minute solution for voters who would otherwise be turned away:

“Bret Healy, a consultant for Four Directions, which is led by members of South Dakota’s Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said the organization believes it has a common-sense solution.

“The group is working with tribal leaders in North Dakota to have a tribal government official available at every polling place on reservations to issue a tribal voting letter that includes the eligible voter’s name, date of birth and residential address.”

A state official told tribal leaders that such letters will be accepted as proof of residency, the Tribune reports.

OJ Semans, the co-executive director of Four Directions, says the group will be “hard-pressed” to get that proof for every eligible voter in the short window of time that’s available, “but that doesn’t mean we’re not going to try.”

Semans, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe/Sicangu Oyate, says that if North Dakota really wanted to help Native Americans vote under the new requirements, it would let the tribes access the 911 numbers in bulk, instead of requiring every individual to do it.

“They figure, ‘If we go one by one, people aren’t going to want to do it, we can drop a few thousand [voters] off just by saying in order for you to vote, you have to call us, go through the hassle,’ ” Semans tells NPR.

Heitkamp called the ID law “burdensome” and once again called for a law to protect the voting rights of Native Americans. She and other legislators have introduced such a bill year after year, unsuccessfully.

“Given the number of Native Americans who have served, fought, and died for this country, it is appalling that some people would still try and erect barriers to suppress their ability to vote,” Heitkamp said in a statement. “Native Americans served in the military before they were even allowed to vote, and they continue to serve at the highest rate of any population in this country.”

The American Civil Liberties Union said the Supreme Court’s decision “enables mass disenfranchisement.”

“In an election that may wind up being decided by just a few thousand votes, the court’s decision could be deeply consequential for the country, not just those who live in North Dakota,” ACLU staff reporter Ashoka Mukpo wrote on Friday.

In 2016, the Harvard Law Review found that Native Americans “routinely face hurdles in exercising the right to vote and securing representation” and that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was only a partial solution to the problem.

Meanwhile Azure, of the Turtle Mountain Band, says that the North Dakota law might have an unintended effect.

“It’s already unified the tribes in North Dakota. Now we’re working together,” he tells NPR, describing the efforts to coordinate letters confirming residents’ eligibility to vote.

“We are members of this U.S. government, and we are not going to let you keep us down. We’re going to figure out a way to to go over the barriers that are put in front of us. … And this unified movement moving forward with the tribes? That’s going to jump our percentages up, with that Native vote.”

Related Stories:

Two bills could make it easier for people in Washington state custody to vote, politically organize

A person walks near the Legislative Building, Wednesday, April 21, 2021, at the Capitol in Olympia, Wash. (Credit: Ted S. Warren / AP) Listen (Runtime 1:04) Read While people who

University of Idaho polling location sees Election Day difficulty

Huge voter turnout and same-day registration caused long delays at UI Student Rec Center

Democrats outraged by ‘horrific’ GOP text messages sent to central Washington Latino voters

Democrats Chelsea Dimas, Maria Beltran and Ana Ruiz Kennedy are running in Washington’s 14th Legislative District in central Washington. They were the targets of some GOP text messages to Spanish-speaking