Meet The Flockers: Ups And Downs Of A Washington Sheepherding Legacy

LISTEN

Before the sun is fully awake, the Martinez brothers are hard at work.

It’s 4 a.m. and they’re driving two hours from Moxee, outside of Yakima, and north to the forested hills around Lake Wenatchee.

There, about 800 sheep wait. It’s all part of the last sheepherding operation in the state that still grazes on federal land.

But this family’s lifestyle and business is teetering on the brink, between its historical legacy and present reality.

All In A Day’s Work

Mark Martinez calls to his sheep with a bellow that bounces off the surrounding foothills. He’s a third-generation sheep rancher following in the path of his grandfather, who emigrated from Spain in the 1920s. He actually started his sheepherding operation with the help of another rancher who paid him in sheep when funds were low.

Mark Martinez bellows out, cajoling the sheep up the ladder and into the truck. His brother Nick stands in the background and watches for any stubborn sheep that hold up the line. CREDIT: ESMY JIMENEZ

ALSO SEE: Sheepherders In Action Photo Essay

Now, brothers Mark and Nick run the operation with their families. The sheep are used for wool and meat. In January, the ewes’ coats are shorn right before they start lambing. That wool is sent to Utah where it’s put up for bid at auction. Lambs are then shipped in late July. The family also has a small number of cattle and horses.

Peruvian “Pastores”

In late September, the Martinez brothers moved about half of those 800 sheep from the mountainous terrain around Lake Wenatchee to the irrigated, emerald pastures of Connell, in Central Washington.

They did it with the help of some highly skilled men: Peruvian “pastores” or sheepherders. All the way from South America, most of them have been with the Martinez family for decades. They come through the a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services program called H-2A.

Mark admits it’s a lot of paperwork to get them here.

“The H-2A process is a lengthy, cumbersome process,” he says.

He’s also the first to recognize the value of the workers.

“Without it, we’d be up the creek without a paddle.”

He’s tried employing local workers before but they washed out after a few weeks. The amount of work and solitude was too much.

His sheepherders have visa permits that allow them to stay up to three years. But they usually return home to Peru around two years, seven months. They spend a few months with their families, then start the cycle over.

The sheepherders live alone with the sheep, care for the sick or injured, and are finely in tune with their needs and the forest around them. Every couple days they move their flock of hundreds of bleating sheep, the old fashioned way — one step at a time. It’s just them, their sheepherder dogs, and a rifle — just in case of coyotes, cougars or bears. And more recently, wolves.

Mark brings supplies, food and water every couple weeks. For the workers but also for the sheep. And when there’s a wildfire he has to be ready to evacuate them.

He explains what it was like during the 2017 fire season.

“Heraclio [a sheepherder] had to take an early exit because of the Jolly Fire. There’s been several others. We’ve had to escort them out, put them on a truck and take them to other areas,” he says. “We haven’t lost any livestock or workers — so far anyway.”

Because Mark’s family has a history of grazing sheep on public lands, he’s inherited a working relationship with the U.S. Forest Service. Carla Jaeger sees the operation firsthand.

She’s a range technician with the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest and works with ranchers on managing their grazing allotments.

Whenever Jaeger sees the sheepherders, she’ll check-in.

“Most of them I know them by name and speak to them just about every time I’m in the area,” she says.

Jaeger helps in everything from precautionary wildfire evacuation to tracking down lost sheep. In some cases, she’ll even help with groceries.

“If Mark’s really busy and we’re headed to the same landscape, sometimes I’ll help him deliver stuff just because it might save him a four-hour drive,” Jaeger says.

Despite federal officials and ranchers sometimes butting heads, Martinez and Jaeger’s relationship is strong.

But that doesn’t mean the operation is always smooth sailing, especially when it comes to land.

Shrinking Parcels, Shrinking Flocks

The biggest threat to their operation is losing grazing allotments. So far, that precious resource has been steadily shrinking.

Before, Mark and Nick could graze sheep closer to home, near the Yakima Army Training Center. But a report by the Pacific Northwest Laboratory in the 1990s recommended grazing be reduced in the area to give the endangered sage grouse a chance to recover.

And when it’s not sage grouse they worry about, it’s wolves.

ALSO SEE: Sheepherders In Action Photo Essay

This year, Martinez lost several sheep in August to wolf predation. He says he had a rider on horseback ahead of the sheep when they entered wolf territory in the Teanaway area, near Cle Elum. And despite noise scare tactics, they still lost sheep.

For a family with a dwindling supply of sheep and land to graze, each animal lost means fewer dollars in their pocket. When the Martinez brothers took over their father’s business, they had 10,000 sheep. Now they’re down to less than half that.

Despite the time it took to wrangle the sheep into the trailers, the going out process is much faster. After a three-hour ride, the sheep are also ready to move around and get to fresh grazing grounds. If you look closely, you can also see an eager sheep peeking its head above the trailer. CREDIT: ESMY JIMENEZ

That’s due to multiple setbacks. First there’s less land to graze on. A hundred years ago, there weren’t as many hikers, bikers, campers, hunters, biologists, and just, well, people out on public lands. Land is limited, and land use ends up splintering the parcels. With all these stakeholders, it’s harder to make policies that work for all parties.

Mark says he respects conservation efforts, but he wishes there was a better solution with wolves. His brother Nick sits on the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Wolf Advisory Group, and they’re invested in finding middle ground.

Mark believes the ideal recovery, “Would be to collar every [wolf]. I know they say it’s not financially feasible but just to give everybody that peace of mind of where they’re located.”

On top of conservation efforts and a shrinking grazing area, the market for wool and meat also fluctuates. Some years are better than others. But in a changing world with so many moving parts, I ask Mark what he thinks his two adult sons will inherit in the next generation of sheepherding.

After a long pause and a shrug, he finally replies.

“That’s the million dollar question.” And when in doubt, the legacy rancher falls back on an old motto: ‘fail to plan and plan to fail.’

ALSO SEE: Sheepherders In Action Photo Essay

Zach Garner contributed research and production for this story.

Copyright 2018 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

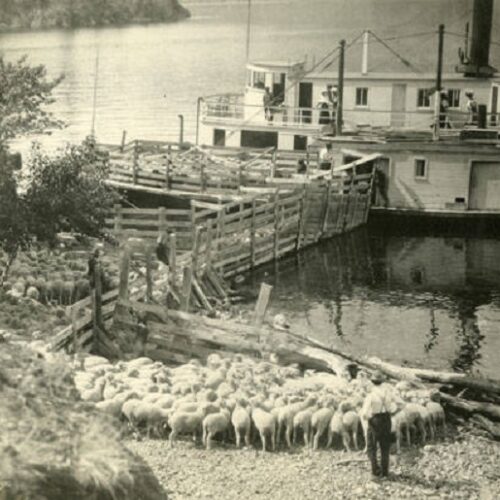

Past As Prologue: Sheep, Ranching And The Beginning Of Industrial Agriculture In The Northwest

Learn how sheep ranchers in the late-nineteenth century in Eastern Oregon were already a part of complex agricultural and industrial systems that provided food, clothing and commodities to markets across the U.S.

Northwest Bighorn Sheep Could Be In Big Danger — From Close Contact And Respiratory Infection

Bighorn sheep in central Washington could be in danger if domestic sheep continue to graze nearby. That’s the concern from two groups suing the U.S. Forest Service. Domestic sheep or goats can pass a deadly bacteria to bighorns.

A Sheepherder On Two Decades In Washington High Country ‘With Your Friends The Dogs’

Heraclio Delacruz is a Peruvian sheepherder, in Spanish what’s called a “pastor.” This is his 18th year with the Martinez family sheepherding operation in Central Washington. ” … you’re alone, with your friends the dogs, the braying sheep,” he says.