Meet The MacArthur Fellow Disrupting Racism In Art

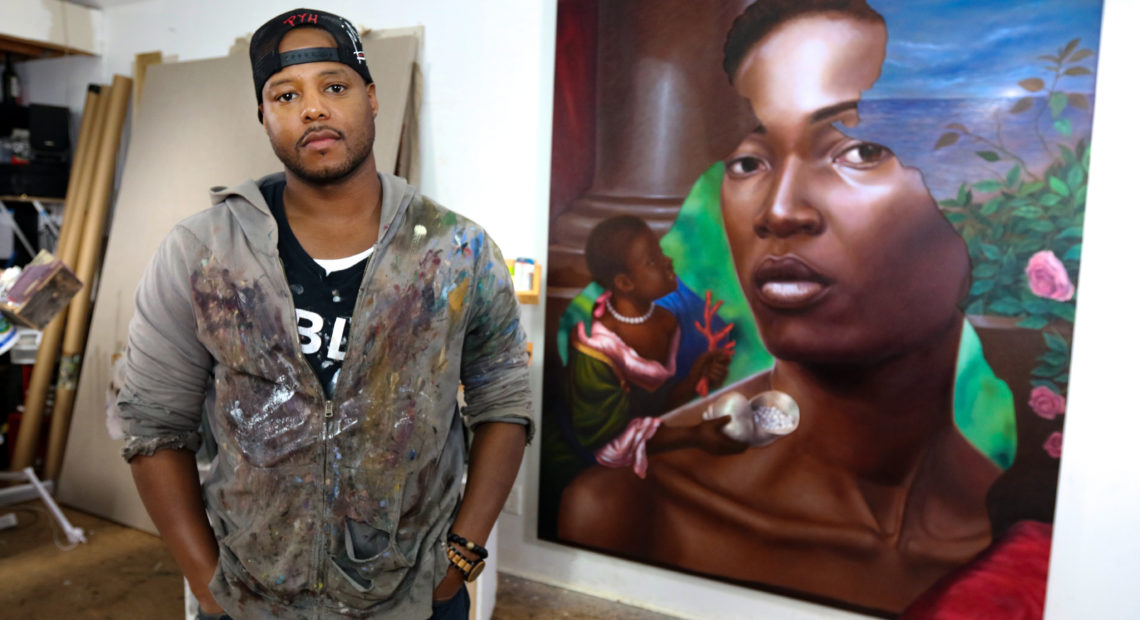

PHOTO: Titus Kaphar often appropriates familiar styles from the Western art canon, but his paintings and sculptures alter the images to point out hidden histories of racism and slavery. CREDIT: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

BY MARY LOUISE KELLY, NPR

Walk into the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. right now and you will find a painting that has been ripped to shreds.

Another one, nearby, hangs half-loose from its stretcher, rumpled. It’s a portrait of Thomas Jefferson; behind it, you glimpse a seated black woman.

They are works by the artist Titus Kaphar. He takes familiar images and remakes them. Maybe he pulls a hidden figure to the front.

His work often confronts the history of slavery and racism in the United States.

“If we are not honest about our past, then we cannot have a clear direction towards our future,” Kaphar says in an interview.

As of today, Kaphar’s work has been recognized with a MacArthur Fellowship — the “genius” grants which come with a $625,000 unrestricted award (paid over five years). The phone call informing him of the fellowship came at his total surprise.

“The truth of the matter is: I did not believe the person on the other end,” Kaphar says. “And in fact, I said, ‘Stop it, who is this?’ But no, they reassured me that in fact it was real.”

(Note: The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is among NPR’s financial supporters.)

Interview Highlights

On the work “Behind the Myth of Benevolence”

Kaphar: So I had a conversation with a American history teacher. And somehow within that conversation there was this phrase that she uttered: “Yes, but Thomas Jefferson was a benevolent slave owner.” And I was sort of shocked by that — I didn’t really understand what she meant. And I asked her to elaborate about it, but she couldn’t, she didn’t. And we sort of sat there in silence for a little bit. I went back to the studio and this is the painting that I made.

I’m not in the business of trying to demonize our Founding Fathers. I don’t really think there’s any benefit to that. But I’m also not trying to deify them. And so that particular piece is kind of pulling back the curtain on these ideas, these illusions, these stories that we tell ourselves about the Founding Fathers.

Kelly: And to do that you’re literally pulling the canvas of the traditional portrait down.

Kaphar: That’s right. And that really has to do with trying to, for myself, find a way in to these concepts physically. So if you were asking yourself a question … how do you make a painting about torture, then you change that and ask yourself the question: What does it mean to torture a painting? Rather than making paintings about something, you make paintings that reflect that thing.

On the current debate about Confederate monuments

We’re having a national conversation right now about public monuments. And in this discussion … we have this sort of binary conversation about keeping these sculptures up or taking them down. And I actually think that that binary conversation is problematic. I think there is another possibility, and I think that possibility has to do with bringing in new work that speaks in conversation with this old work. It’s about a willingness to confront a very difficult past. …

Let me be absolutely clear. If we are continuing that binary conversation where we’re saying “either keep it up or take it down,” take it down. I don’t feel in love with these sculptures — that’s not what this is about. What I’m saying is: The binary conversation doesn’t bring all of the issues into consideration. So there’s a third option. The third option is: We engage our contemporary artists of this time. In the same way that the WPA did, we bring in contemporary artists, we have them make sculptures that exist in the communities that they live in, we present those sculptures in the same community squares where these Robert E. Lee sculptures exist, we pull these Robert E. Lee sculptures down from the pedestal, bring them at the same level as these new contemporary works, and we force these works to engage one another. I think one of our challenges is that we sort of consistently try to make public sculpture in a way that it’s a sentence with a period at the end. And inevitably it’s not — it’s a comma, and there should be a clause after that.

Melissa Gray and Matt Ozug produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Patrick Jarenwattananon adapted it for the Web.