Another Puget Sound Orca Struggles, But 3 Others Are Pregnant

The lean profile of the whale known as K25 is yet another sign of trouble for the region’s endangered orcas.

The Globe and Mail reported last week “dismal” returns of chinook salmon in British Columbia’s Fraser River, one of the most important food sources for the southern resident killer whales.

Since last November, three members of the long-endangered population have died, most recently an emaciated young female known as J50. Her death, despite intensive efforts to find and medicate her, dropped the fish-eating orcas’ numbers to 74, the lowest in 30 years.

“While the decline in K25’s body condition is not as severe as we saw with J50 this summer, it is a warning signal,” Lynne Barre, of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said in a press release.

At 27 years old, K25 is nearing the average 30-year lifespan for a male orca.

NOAA officials said they are not planning to intervene to provide veterinary care at this time.

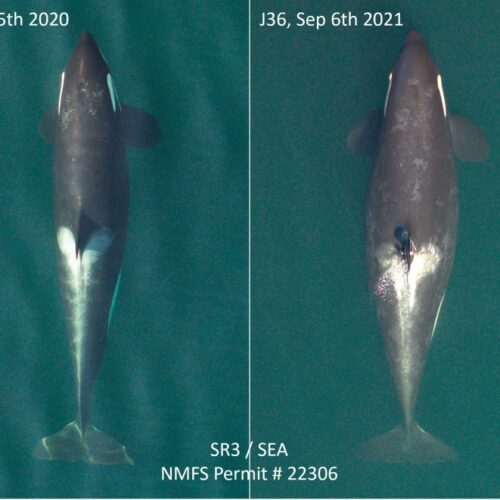

Aerial photography has also revealed bulging bellies on at least one orca in each of J, K and L pods: females well into their 18-month pregnancies.

NOAA officials welcomed that news. Still, most local orca pregnancies in the past decade have ended in miscarriage, probably due to malnutrition. One of the currently pregnant whales, K27 (K25’s sister), had miscarried in 2016 and was photographed carrying the fetus to the surface on her nose.

On Tuesday, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee’s killer whale task force released 45 draft recommendations for ways to boost births and reduce deaths among the remaining orcas, including curtailing boat noise and protecting salmon streams. The proposals, aimed at increasing the southern residents’ population by 10 whales over the next 10 years, are open for public comment until Oct. 7.

The task force’s next big meeting is scheduled for Oct. 17-18 in Tacoma. Recommendations are to be finalized in November for elected officials to adopt, adapt or ignore.

Copyright 2018 KUOW

Related Stories:

Reducing collisions between ships and whales? There’s apps for that, but they need work

Fortunately, it doesn’t happen very often in the Pacific Northwest that ships collide with whales. But when it does, it’s upsetting, tragic and the whale probably dies. Three separate teams have developed smartphone-based systems that can alert commercial mariners to watch out, slow down or change course when whales have been sighted nearby. A recent ride-along on a big container ship demonstrated that real-time whale alerts are still a work in progress.

Babies On Board! Three Endangered Northwest Killer Whales Look Very Pregnant In Aerial Photos

Research photos taken with a drone show multiple killer whales are close to giving birth in one of the Pacific Northwest’s critically endangered pods. The late-stage pregnancies stirred excitement among whale watchers — and also renewed worries about the availability of adequate food supply for the mothers and babies.

Study: Chinook Salmon Are Key To Northwest Orca Population All Year

By analyzing the DNA of orca feces as well as salmon scales and other remains after the whales have devoured the fish, the researchers demonstrated that the while the whales sometimes eat other species, including halibut, lingcod and steelhead, they depend most on Chinook. And they consumed the big salmon from a wide range of sources — from those that spawn in California’s Sacramento River all the way to the Taku River in northern British Columbia.