Oregon Now Has A Hypoxia Season, Just Like A Wildfire Season

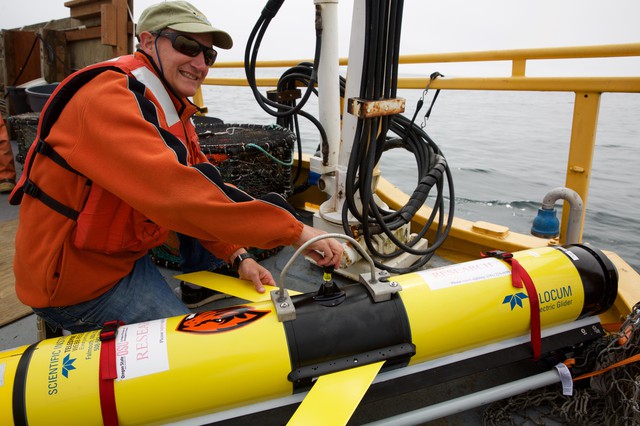

Oregon State University oceanographer and co-chair of the Oregon Coordinating Council on Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia, Jack Barth, is collecting data to draw the first hypoxia maps of Oregon’s coast.

“We’re actually seeing real interest from the fishing community. They know how to look at our data and say, ‘Where are the layers in the ocean? Where is the high and low oxygen?’” Barth said.

Barth said some Oregonians who make their living from the sea have been aware of the problem for a long time and brought it to the attention of researchers.

“Scientists keep saying that the ocean is changing along with the climate, and people are beginning to get in tune,” said Barth. “They see the heat waves and all the smoke from wildfires and are beginning to realize that this is something different.”

“The crabbing and the oyster industries were ahead of the curve. They were among the first to notice that the ocean just off our coast is changing and was affecting their livelihoods. And they have been working with scientists ever since.”

Those same industries alerted people to a different problem — ocean acidification — in 2007. The Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery on Netarts Bay experienced massive die-offs of larval oysters. That threatened to destroy the hatchery’s entire operation.

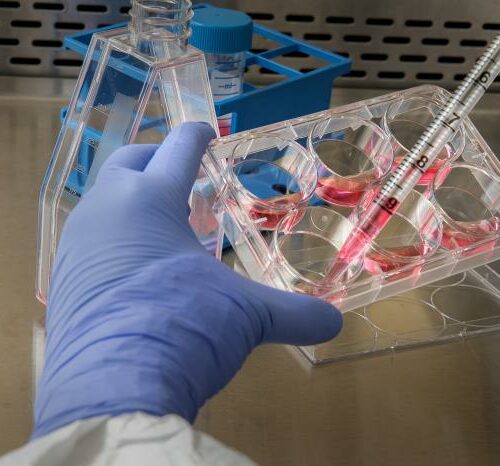

OSU researchers Burke Hales and George Waldbusser responded and found the problem was highly acidified water and that the hatchery could mitigate it by drawing water from the bay at certain times of the day, or treating the water to lower its corrosiveness.

Further research found acidification didn’t destroy oyster shells but prevented them from developing in the first place.

“Scientists from Oregon State have been involved since day one on both the emerging challenges of coastal ocean hypoxia and ocean acidification,” said Caren Braby, marine resources program manager at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and co-chair of the Oregon Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia Council.

NOAA fisheries biologist, Curtis Roegner records scientific data on the health of crab populations. Low-oxygen levels have killed off large populations of crabs during hypoxia events in the past. CREDIT: KRISTIAN FODEN-VENCIL

Scientists say rising levels of carbon dioxide, attributed to the burning of fossil fuels, are major drivers of increased ocean acidification.

In its first biannual report to the Legislature, Oregon’s Hypoxia Council said the state needs more monitoring and policy direction on this problem.

Ocean acidification sensors in rock pools. CREDIT: OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

Copyright 2018 Earthfix

Related Stories:

Ecologists help with burrowing owl ‘spring cleaning’ at Umatilla Chemical Depot

Lindsay Chiono, wildlife habitat ecologist for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR), does some seasonal maintenance, or spring cleaning, on one of the 180 total artificial nesting

Washington, Idaho rank high for public health emergency preparedness

Both states saw steady or increased funding for public health, but Idaho still among lowest for vaccinations.

Washington state reports 7-year peak in influenza-related deaths

The Washington state Department of Health reported on March 20th that influenza activity reached its highest levels in seven years, with the most flu-related deaths since the 2017-2018 flu season.