Fighting Wildfire Is Risky. But It’s Become Riskier Than It Needs To Be

LISTEN

PART 1

PART 2

The Forest Service says too many wildland firefighters are exposed to hazards on the fire line and that it must change its ways. Families like the Hammacks know the stakes all too well.

Jay Crawford was face-first against the dirt. Somehow, he was still alive.

He looked around the forest and checked himself over to make sure he really was.

Then he glanced downhill toward his friend John Hammack. Crawford saw brush and the giant trunk of a fallen Douglas fir.

No sign of Hammack.

He shouted. No answer.

* * *

On the morning of Aug. 1, 2013, Crawford and Hammack had set out to cut a single Douglas fir tree burning in the woods outside Sisters, Oregon.

It was a big tree, at least 5 feet across, with branches too thick to see the top. Lightning struck it a day earlier. The fire hadn’t spread, but the Forest Service feared it would. Two firefighters tried to chainsaw through the tree a day before but barely made a dent. So they called in the professional fallers.

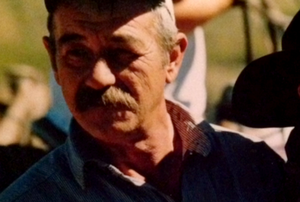

John Hammack. CREDIT: KELLI JO HAMMACK

Cutting timber is dangerous work — more so with fire in the mix — but Crawford and Hammack were no strangers to it. Both were experienced loggers. Crawford, 48, worked for the local fire department. Hammack, 58, had grown up in those woods outside Sisters.

Hammack didn’t love working fires, and he hadn’t in several years. But the money was good. He was excited about the job.

Maura Hammack, his wife, remembers that morning. How John howled at the coyote pups in the brush outside the home they’d built near Madras.

She watched him put on firefighting greens and yellows instead of his usual hickory shirt and logger jeans. He laced up the cork boots he’d broken in so hard they wore parts of his feet to bone.

He headed for his pickup to meet Crawford.

Hammack, a man who gave few words and asked for few in return, gave these to his wife on his way out: “Pray for me, baby.”

Fighting wildfire is inherently risky, but it has become riskier than its needs to be.

Federal and state agencies have come to realize fires should not be fought at all costs and, in fact, many should not be fought at all. Excluding natural fire led to forests burning in bigger, more destructive ways. Each year, hazardous fuels accumulate faster than we can reduce them through selective logging and burning.

The U.S. Forest Service and other wildland fire agencies continue aggressive suppression on nearly all fires, with few considerations of the long-term risk. That needlessly endangers firefighter lives on the front lines of massive blazes where there’s little hope of suppression — and on small fires in the backcountry that could be left to burn with little risk to anything of value.

“You can get me all riled up here,” said Vicki Christiansen, interim chief of the U.S. Forest Service. “To have to go to one more funeral of one of our own who was taking action when what they were doing had low probability of making any difference, that’s what we call unnecessary exposure. And I’ll say that’s unnecessary loss of life.”

The change of pace at her agency, Christiansen admitted, resembles the turning of the Titanic.

* * *

Crawford drove his pickup toward the job briefing with Hammack in the passenger’s seat. As they drove, they talked of family.

Hammack lingered on the subject of his daughter, Kelli Jo, who was grown with kids of her own.

He couldn’t shake fatherly worries about his daughter’s boyfriend. He loved Albert Rollins like a son, but perhaps saw too much of his own younger self in him. He was planning to sit and talk with Rollins that day — straighten out, he’d say, no more drinking, take care of my daughter — until he was called to the fire.

Kelli Jo Hammack figured she’d see her dad that day. Her daughter was showing a pig for 4-H at the county fair.

Five grandchildren were the tough man’s softest spot. Hammack shaved his mustache after Kelli Jo’s oldest daughter was born, so that everyone would see their resemblance. He rarely missed their rodeos, sports games or school events.

“I didn’t even know that he got called out on a fire,” Kelli Jo Hammack said. “I was waiting for him.”

* * *

When Crawford and Hammack reached the tree, Crawford saw how his friend was sizing it up and knew he wouldn’t get to touch it.

“I could just tell, he was in charge and he was gonna cut it,” Crawford said. “Typical for John.”

They took turns felling smaller trees, clearing a path for the giant to fall. As they walked back to their target, Crawford found footing slightly uphill, Hammack below.

Crawford felt a slight breeze. He thinks, maybe, that’s what made him look up.

That’s when he saw it.

It looked like a school bus falling from the sky. Weakened by the fire, the top of the tree had snapped off and they were underneath it. Crawford screamed to Hammack and scrambled uphill.

“I knew I was dead,” he said.

There are other ways to handle a single burning tree.

“I’ve had my crews and professional fallers fall a lot of snags that weren’t even burning,” said Chris Dunn, a wildland firefighter for eight years who now studies risk management at Oregon State University. “I look back on those today and say, well, we probably could have easily made a different decision and not even had to bother doing that.”

You could clear a fire line farther back and wait for it to come down or burn out, though the uncertainty can scare fire managers.

The decision to cut that burning tree might have been the right one, but too often that approach is the default without question, said Dunn, who now works on a Forest Service team that uses data to better inform when and where the agency deploys its firefighters.

Oregon State University professor Chris Dunn examines a map of the likelihood of success for fire suppression in southern Oregon. Dunn is part of a Forest Service team using data to improve decision-making and risk assessment. CREDIT: TONY SCHICK

“It’s not about targeting the firefighters and their efforts and their hard work. Their work is fundamentally important,” Dunn said. “Really the question then needs to be asked, should we even be doing this here?”

This year, the Forest Service completed an assessment of wildfire risk on Northwest lands. It shows the area in which Hammack and Crawford’s tree fell is one where, under the right conditions, the benefits of allowing a fire to burn outweigh the risks.

That was not known then. At the time, hot summer months were ahead. Firefighting resources were stretched thin. The tree was far from homes but in between were acres of thick, dry forest full of dead standing trees, known to firefighters as snags.

The Forest Service declined an interview about that day, instead citing a 2013 review of the incident. The report acknowledges the value in assessing a hazard tree rather than rushing to fell it. It also states the decision to take the tree was sound: “A decision to not take down the tree is a decision to involve potentially hundreds of firefighters, working in snag infested country over a long period of time.”

* * *

Crawford’s back and shoulders ached. He didn’t know it, but the blow from the tree broke both his shoulder blades and tore his rotator cuffs.

He did his best to ignore it. He knew Hammack could be under the tree. He started to dig.

Crawford went along and around the giant log and pulled loose tree limbs aside, hoping he’d find his friend unconscious, but alive, under a mess of twigs and needles.

In 2013, Jay Crawford was working as a firefighter in Sisters. He now lives in Kamiah, Idaho, and works for the Life Flight Network. CREDIT: TONY SCHICK

But with each pile of brush and branch Hammack wasn’t under, Crawford grew more certain of the worst: Hammack was crushed by the falling tree.

The Forest Service incident commander and a trainee heard the tree fall and Crawford’s calls for help. They came racing in and asked where John was.

“If he’s going to survive he’s going to be in these green branches,” Crawford yelled to them.

His pain was getting worse. He knew if he didn’t leave the scene soon he wouldn’t make it out on his own. He pointed out the last places he thought Hammack might be. The search continued, but as Crawford walked out of the woods, he already knew.

“I never even saw a piece of him,” he later said.

Crawford ended up in a hospital bed. His wife and daughters came to visit. It was all sinking in.

“It was just a sick, awful feeling for a long time,” he said.

Despite advancements in technology and training, wildland firefighters continue to die at what Forest Service leadership has called an appalling rate.

More than a thousand people have died fighting wildfire in the U.S. since 1910. Nearly a quarter of them died in the past 15 years. Some die in tragic, headline-grabbing fires like Yarnell Hill, which claimed the lives of 19 hotshots from Prescott, Arizona. Many die on fires you’ve never heard of.

“I think at least 20 people have lost their lives on fires that I was in some way responsible for,” said Jim Peña, who spent five years as the Northwest regional forester, overseeing Oregon and Washington for the Forest Service. He retired in July. “I look back on those and I say, ‘Those people didn’t need to die.”

Because aggressive fire suppression is needed in many places throughout the West, it is unavoidable that firefighters will be exposed to potentially fatal hazards.

But researchers have found fire managers’ actions can unnecessarily expose wildland firefighters to danger. Surveys of fire managers show a tendency to favor more expensive, aggressive tactics regardless of expected outcome or exposure to personnel. A study in 2017 found fire managers order more resources for building fire lines than necessary and after fire growth has ceased, which has the potential to unnecessarily put firefighters in harm’s way on the fire line. Other studies have found firefighting resources used in situations where they’re unlikely to be effective.

A 2017 Forest Service research paper posits that “exposing responders to hazards in order to protect low-value resources while perpetuating feedbacks that increase long-term risks might be beyond the pale.”

The Forest Service’s latest risk management research, the kind OSU’s Chris Dunn works on, maps where suppression efforts are most difficult, where control lines are likely to succeed, and where fires can be more safely reintroduced on the landscape. The agency has started testing improved risk management on a handful of wildfires each summer.

But few are comfortable with the idea of the forest on fire, most of all those who see their homes and livelihoods in those trees.

That’s why the idea of backing off some wildfires can be a hard sell, even amongst those who have paid the highest price of fire suppression.

Crawford thinks fires are not attacked aggressively enough anymore. There is too much red tape, too little direct action.

“I can see where it make sense to let fires burn. But with houses built up in surrounding areas so much more, you know,” he said. “It’s just so much more risk and there’s so much more fuel now because of lack of management of our forests and suppression, it’s hard to just let fires go.”

Hammack’s wife and family want to see more forests in private management, preferring them logged before they burn.

Hammack despised the new big business of fire that replaced logging in much of the woods. He thought the Forest Service let fires burn for too long. He often referred to the nation’s forestry agency as the ‘Forest Circus.’

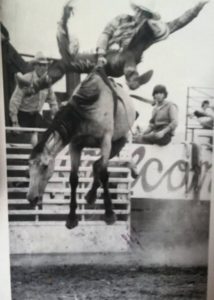

Kelli Jo Hammack and her brother, Johnny, ride on the back of their father, John Hammack. John, an accomplished rodeo rider and logger, was killed by a falling tree while working a forest fire in 2013.

Courtesy of Kelli Jo Hammack

“Not my dad,” she kept thinking.

The day her dad died, Kelli Jo Hammack caught a ride to Crawford’s house to fetch his old brown Dodge pickup. She wanted to smell her dad, to feel close to him.

“I just kept thinking he’d come walking out of the woods saying, ‘You guys wouldn’t believe what happened to me,’” she said.

She hadn’t met Crawford before. He came out of his house, bandaged, and hugged her.

As the days passed, she still couldn’t wrap her mind around her father’s death: Did he feel it? Did he burn? She was having dreams of him stuck under a burning tree, asking for help. And she couldn’t.

She decided she needed to see the tree. So one night, she drove out Highway 242 not knowing where it was but figuring she’d get close.

It was there in the dark that Crawford found her.

He’d caught wind of her plans from a friend and hopped in the car. He was worried she’d get lost or do something crazy — he knew how upset she was.

Crawford had promised he’d take her to the fallen tree, but they didn’t make it far. It was too dark and steep. So they sat, and he told her about her dad’s last day.

In the weeks and months that followed, Crawford joined the Hammacks at memorials and services. He came by the house John built to help remodel a barn. Mostly, they just talked.

“Kelli Jo is always saying how grateful she is and what I do for them,” Crawford said. “It’s funny. It’s a huge gift to me. It helps me so much.”

Crawford couldn’t get a good night’s sleep for a year after the incident. Therapy helped. He said he doesn’t blame the Forest Service, and eventually stopped blaming himself.

“It’s a dangerous job. Things played out the way they did,” he said. “And it’s not going to stop. I mean we’re going to continue to have tragedies like that.”

Jay Crawford moved to Kamiah, Idaho, a few years after surviving a fatal wildland fire incident. He says no one is to blame: “It’s a dangerous job, things played out the way they did,” he said. CREDIT: TONY SCHICK

Crawford and his wife, Debbie, moved from Sisters to remote Kamiah, Idaho, overlooking the Clearwater River. He could hunt his favorite spots in the nearby Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness.

But he still wasn’t happy, his wife would tell him. She knew by his laugh.

Crawford became more religious after Hammack’s death. He became more focused on his family, hoping to better connect with his three daughters. He searched for the answer to why he’s still alive.

“Sometimes I’m grateful I am. Sometimes I wonder why I am,” he said. “When I get really down, really depressed, I wish it had been me rather than John.”

* * *

Kelli Jo Hammack sat at the kitchen table with Maura Hammack, Albert Rollins and memories of dad. On her iPhone, she opened a tribute video.

It began with the strum of a country guitar and a black-and-white photo of Hammack riding a tricycle as a small boy.

“I haven’t watched this in forever,” she said. “It’s probably gonna make me cry.”

Maura Hammack, left, Albert Rollins and Kelli Jo Hammack stand in front of their house outside Madras, Oregon. John Hammack, the patriarch of the family, was killed in 2013 by a burning, falling tree. CREDIT: TONY SCHICK

The family has struggled with why he was under that tree that day.

“Dad and Jay went out there trusting that the Forest Service had done their job,” Kelli Jo Hammack said. “You should have a system in place of checks, and other checks, accountability and reasoning. If that would have happened, Dad would not have been in that situation.”

“They make a decision and risk somebody’s life based on something they’ve been watching for days, and they determine it’s safe?” Maura Hammack said. “Nobody would be standing under that tree with a chainsaw unless they said, ‘We want you to do that.’”

John Hammack never wanted to be told when something wasn’t safe. He grew up the hard way: One of eight children, eating mostly venison and canned food because he had no refrigerator. He hung around the rodeo grounds and broke his first horse when he was about 8 years old.

Throughout life when he felt sick, he’d inject himself with a shot of horse penicillin from the feed store. He’d ask Kelli Jo, now a nurse, to stitch up his leg or pull staples out of his head when she was a kid.

In his youth, Hammack was a bareback rodeo rider prone to the occasional drink and fight.

John Hammack had an accomplished rodeo career. He also worked as a logger. Later in life, he raised horses and taught kids to rodeo outside Madras.

Courtesy of Kelli Jo Hammack

“He did this 180 in life,” Kelli Jo said. “He was a tough, tough man. But, soft.”

Maura Hammack met him on a job site where she was wiring a house. His rodeo days had ended. Logging jobs were fading. He was divorced and his kids had left home. He was drinking a lot.

“He was a little lost,” Maura said.

They built houses, raised horses and Hammack always found a kid to teach bronc riding.

“We made a different life together,” she said.

Before he died, Hammack saw his daughter’s boyfriend in the same dark place he had been. He feared what it would mean for her.

After he died, his last conversation about those worries weighed heavy on Crawford.

Crawford had grown close with Kelli Jo. He felt he owed it to Hammack to watch over her.

So he sat down with Albert Rollins, a man he’d mentored as a logger, and he relayed their friend’s parting message.

Five years later, Rollins and Kelli Jo Hammack are married.

And Kelli Jo couldn’t help but see it.

“You’re just so much like Dad,” she’d tell him.

Copyright 2018 Earthfix

About this story

What questions did we set out to answer?

In a previous story, we examined how the Forest Service and other wildland fire agencies suppress thousands of wildfires ever year when in fact many could instead be managed to reduce hazardous fuels and lower the risk of extreme fires. We set out to answer the question of what this practice of all-out fire suppression, decades after the agencies recognized the problems it caused, meant for the risk to firefighters.

Who is in this story?

This story focuses primarily on the survivor and surviving family members of a single fatal wildland fire incident. We told the story of John Hammack’s death because it underscored the challenges in making risk-based decisions in wildland fire. The story also includes interviews with the interim chief of the Forest Service, the former Northwest regional forester and a former wildland firefighter who now studies risk management in the aim of reducing exposure to wildland firefighters. We also conducted several interviews with wildland fire advocates, scientists, firefighters and safety experts who were not quoted in the piece but informed the reporting.

Were there tough journalistic decisions to make?

We wanted to be especially careful in how we connected the story of one timber faller’s death to the overall picture of wildland firefighting, and to make sure we included various viewpoints. The researchers who argue not all fires should be fought say so because they want to minimize exposure to people like Jay Crawford and John Hammack.

But there are many — Crawford, Hammack and Hammack’s family among them — who do not see it this way. They live in rural areas affected by fire, they are involved in logging and they see the danger in not putting out a fire as fast as possible. There are many nuances to a story like this, and it can be a challenge to capture them all.

How can you respond or get involved?

You can contact elected officials, the Forest Service, the Interior Department or state forestry agencies about wildfire management. You can contact us about our coverage at earthfix@opb.org.

Related Stories:

Trash piling up, wildfires too big to fight: What wild lands might look like without workers

Mountain peaks are reflected in the waters of Lake Colchuk, located in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area. Smoke from a nearby wildfire hangs in the air. (Credit: Theresa Rivers) Listen

Final cohort of Idaho firefighters homebound after two weeks in California

Idaho Task Force Four poses for a photo near the ocean at the end of their two-week service in Los Angeles, California. (Courtesy: Billy Monahan) Listen (Runtime 1:03) Read The

Tacoma City Council moves forward with budget, directs additional $2.5 million to fire department

The Tacoma City Council adopted its next two-year budget, after months of working with city staff to balance for a predicted $24 million structural deficit.