Ruling Favoring Homeless Individuals Could Have Big Impact On Northwest Cities’ Anti-Camping Laws

Listen

The city of Portland will not change how it enforces its anti-camping law, following a sweeping opinion by a federal appeals court on Tuesday that similar rules might violate the constitutional rights of homeless citizens.

Tracy Reeve, attorney for Oregon’s largest city, said Wednesday morning her office had reviewed the opinion by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, and believes Portland’s rule outlawing camping on public property is still legal.

“When the ruling came down yesterday morning we immediately convened a team of lawyers in order to evaluate whether the City’s current practices were in conformity with the decision,” Reeve wrote in an email to OPB. “We determined that they were.”

Meanwhile, advocates for the homeless cheered the ruling, predicting widespread changes in how cities in western states enforce anti-camping rules.

The 9th Circuit opinion puts into force a legal theory that has been argued for more than a decade by attorneys in Oregon and elsewhere. The circuit is comprised of nine states in the western U.S., including the entire West Coast, as well as two territories.

A panel of three appeals judges for the circuit found that a camping ban in the city of Boise could violate Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment if homeless people have no choice but to camp.

“As long as there is no option of sleeping indoors, the government cannot criminalize indigent, homeless people for sleeping outdoors, on public property, on the false premise they had a choice in the matter,” Judge Marsha Berzon wrote in the opinion. Later, she added: “An ordinance violates the Eighth Amendment insofar as it imposes criminal sanctions against homeless individuals for sleeping outdoors, on public property, when no alternative shelter is available to them.”

The ruling was similar to one the appeals court made in a case out of Los Angeles in 2006, but that opinion was vacated under a settlement between the parties. Now the legal precedent is back in force — with potentially large consequences for cities.

“It puts cities on notice that they cannot enforce laws that have this punishing effect on our most vulnerable neighbors when they are simultaneously not providing safe and legal places for people to go,” said Sara Rankin, an associate professor at the Seattle University School of Law. “This decision will force cities to provide sufficient safe and legal places … for people to be.”

According to a 2017 report from the ACLU of Oregon, more than 25 cities in the state have rules outlawing sleeping or camping in public.

Portland’s law, in particular, has been challenged over the years. In 2000, a Multnomah County judge ruled the ordinance was unconstitutional for the same reason the 9th Circuit ruled against Boise’s law, but the ruling ultimately had little effect.

Then in 2015, a homeless woman named Alexandra Barrett challenged her arrests in Portland in connection with the camping law. Among her arguments was that the law violates her Eighth Amendment rights.

A circuit court judge disagreed, but Barrett’s case is currently before the Oregon Court of Appeals. Attorneys challenging the Portland law in that case planned to file a memo with the court Wednesday highlighting the ruling in the 9th Circuit.

“The 9th Circuit case isn’t binding on the Oregon Court of Appeals, but it is very persuasive, since Boise’s ordinance is so similar to Portland’s,” said Lindsey Burrows, who’s representing Barrett.

But Reeve, the Portland city attorney, contends the recent opinion has no bearing on Portland’s law — largely because of how the city has chosen to interpret the law. She quoted her office’s arguments in the ongoing Barrett case.

“What [the law] prohibits, then, is for a person to set up or remain at a ‘campsite’ on ‘public property or public right of way’ for the purpose of ‘making their home’ or ‘residing’ in that particular place,” Reeve wrote. “It does not prohibit persons from sleeping on public property or public rights-of-way so long as they do not intend to ‘dwell,’ ‘reside,’ or ‘make their home’ in those places.”

Asked to elaborate on the line between sleeping on a sidewalk for several nights and residing there, Reeve declined.

Rankin, the Seattle University law professor, expressed skepticism about Reeve’s reasoning.

“I would challenge anybody to go around in any meaningful way and try to determine person by person, how long that person intends to stay there,” she said.

The wording of the city’s ordinance is more simple than the distinction Reeve drew. It outlaws campsites in public, and defines a campsite as “any place where any bedding, sleeping bag, or other sleeping matter, or any stove or fire is placed, established, or maintained, whether or not such place incorporates the use of any tent, lean-to, shack, or any other structure, or any vehicle or part thereof.”

Not everyone has reached conclusions as quickly as Reeve’s office.

Rod Underhill, the Multnomah County district attorney, said Wednesday his office has seen the new opinion and is “going to begin reviewing it and its potential implications.” Underhill’s office could not immediately provide stats on how many cases related to illegal camping it has filed in recent years.

The Portland Police Bureau is also aware of the ruling, according to spokesman Sgt. Chris Burley. Burley said a “cursory” search of bureau records turned up just four instances of officers using the law since 2016, but he cautioned that number was potentially unreliable.

“Officers will continue to respond to calls for service regarding illegal activity and livability issues and attempt to work with community partners and identify solutions that place the least amount of focus on enforcement as practical,” Burley wrote in an email.

Officials who administer homeless shelters in the city say Portland’s sizable unsheltered homeless population — more than 1,600 people according to a recent count — frequently have limited options. The city has around 1,000 year-round shelter beds for homeless adults, with more reserved for families, domestic violence victims and minors.

“By and large, we are full every night,” said Denis Theriault, spokesman for the Multnomah County Joint Office of Homeless Services, which funds homeless shelters in the county.

Some cities haven’t waited until a court ruling to change their policies.

Vancouver, Washington, has operated under a modified camping ordinance since 2015, not long after the U.S. Department of Justice took the positionthat homeless people shouldn’t be penalized for sleeping outdoors if they had no other choice. According to the city’s website, “it is now legal to camp overnight on most publicly-owned property in Vancouver between the hours of 9:30 p.m. and 6:30 a.m.”

Copyright 2018 Oregon Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Unpacked: Addressing homelessness in Walla Walla

Walla Walla’s low-barrier shelter allows people to live with their pets or their partners. That’s a rarity in the shelter world — and a critical tool in the region’s efforts

How one Washington county is making progress on homelessness

Walla Walla’s collaborative approach is helping people like Matthew Cate get housed. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 4:00) Read Editor’s note: This story is part of NWPB’s efforts

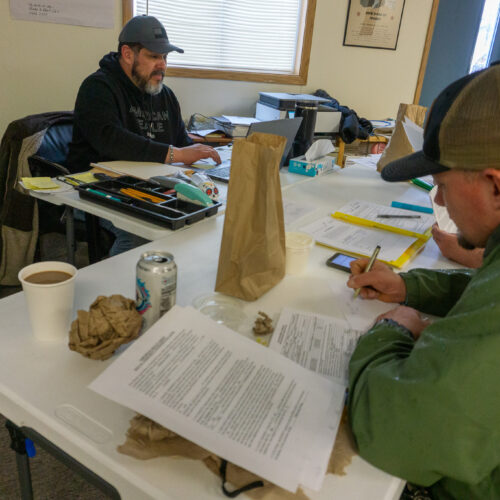

This ‘Ready to Rent’ course is preparing people to exit homelessness

Dustin McCauley fills out a worksheet as Ricky Aguilar teaches the Ready to Rent course. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 1:02) Read On a rainy Wednesday, Ricky Aguilar