Northwest’s Ancient Earthquakes May Help Predict Future Risk

Listen

One way to predict the risk of earthquakes in the Pacific Northwest is to look at how often they occurred in the past – and, for several groups of geologists, delving into the fault lines themselves.

Geologists from Western Washington University, Portland State University and the federal government this summer have discovered signs of strong earthquakes that struck the Pacific Northwest long before modern settlement. The evidence lies in trenches the scientists cut across fault lines in northwest Oregon and on the north Olympic Peninsula.

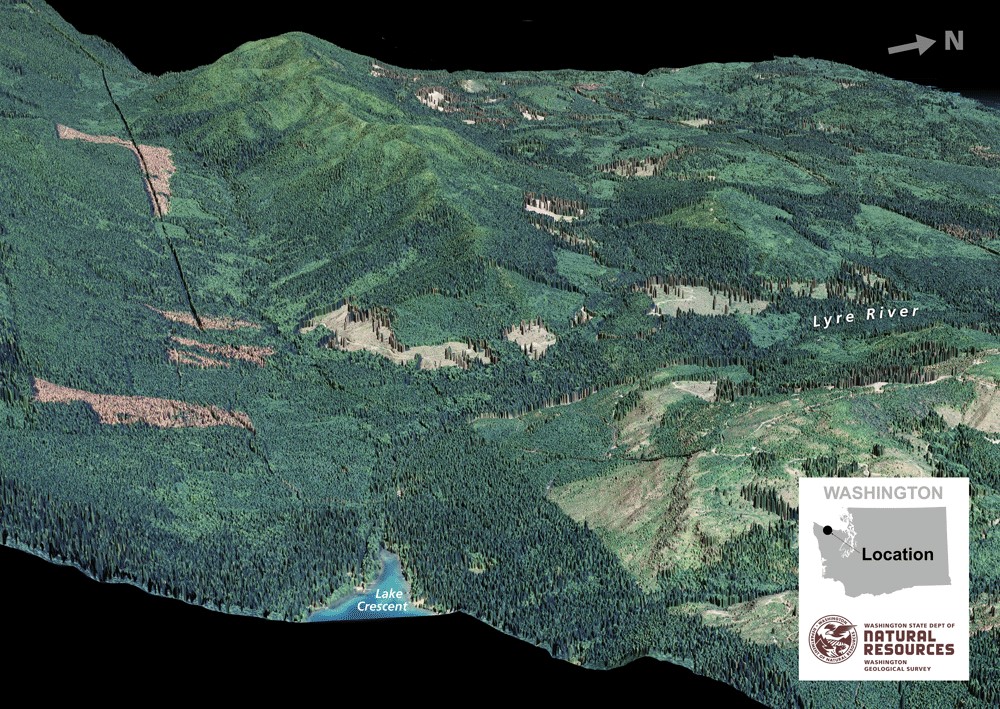

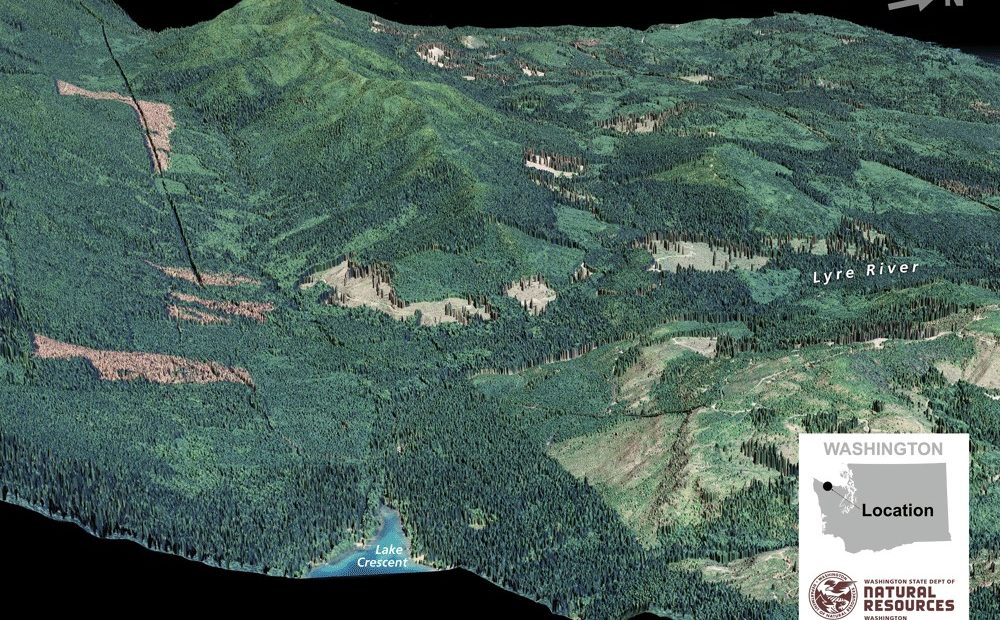

The Sadie Creek earthquake fault surfaces southwest of the small town of Joyce. WWU Professor Liz Schermer led two excavations that bisected the fault, scraped the trench walls clean and then looked for offset layers overlaid with landslide debris probably triggered by a quake.

One of the trenches exposed evidence of five earthquakes over the past 15,000 years. The second trench had traces of three quakes in the past 8,000 to 9,000 years.

“We think they were probably close to magnitude seven,” Schermer said.

The Sadie Creek fault is one of dozens of crustal faults on land in the Pacific Northwest. These rupture less frequently than the source of the better known “Big One”—the offshore Cascadia subduction fault zone—but collectively they present more risk because they are shallow and closer to population centers.

A study trench reveals the earthquake history of the Sadie Creek fault southwest of Joyce, Wash. CREDIT: ROBERT WILLIAMS/WWU

“We’re planning to use radiocarbon dating to find out the ages of each earthquake,” Schermer said in an interview Tuesday. “We know there have been five earthquakes in the last 15,000 years or so, but we’d like to know, were they all in the last 5,000 years or were they spread out evenly over those 15,000 years?”

Once Schermer and her team find those answers, the data will be used to inform a seismic hazard report for local communities and the state, Schermer said.

Geologists in the Northwest keep discovering more and more active shallow, crustal faults that deserve further investigation, thanks in large measure to an imaging technology called LIDAR. When mounted on an airplane, LIDAR uses pulses of laser light to pierce the foliage of trees and bushes and map the ground underneath.

Still, relatively few faults have been trenched, Schermer said. It’s also rare to get a long, dateable record of earthquakes in an individual trench.

“It is pretty special,” Schermer said about the results of this summer’s excavation.

The researchers brought in a backhoe to dig the two Clallam County trenches, which are about 60 feet long, about six feet deep, and will be covered up again come October. The trenches are on partially-logged state forest land.

Separate trench excavations happened this summer along the Gales Creek Fault in Oregon’s Coast Range, roughly a 45-minute drive west of Portland. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation researchers cut into the fault in one location while a Portland State University team hand-dug another trench about five feet deep in the Forest Grove watershed nearby.

“It’s a pretty obvious seismic hazard and it’s close by,” said PSU Geology Professor Ashley Streig to explain the focus on this fault. “We’re finding it’s an active fault.”

Streig said the PSU trench contained evidence of two prehistoric earthquakes on the fault, with numerical dating pending. She said she hopes to bring in a backhoe once fire season ends to deepen her trench.

Related Stories:

Some freeways may be useable following ‘the Big One’ per new modeling by UW

New modeling by the University of Washington of the impacts of a major Cascadia earthquake offers a less dire picture of the aftermath of the so-called “Big One” — specifically when it comes to highway bridges.

Concert in Pasco To Raise Disaster Relief Funds For Colima in Mexico

The Mid-Columbia Symphony will perform a public concert this September 24th in Pasco at 6:00 p.m. Photo from Mike Gonzalez reports website. Listen (Runtime 0:53) Read A symphonic concert will

Coastal Washington Tribe Creates Higher Ground By Building Tsunami Tower, First Of Its Type Here

There is a new option to escape a tsunami if you’re on the southwest coast of Washington when the Big One strikes. The Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe on Friday dedicated a 50-foot tall evacuation tower in Tokeland, Washington. Tribal leaders and the Federal Emergency Management Agency said the new tsunami refuge platform should be an example and inspiration for other vulnerable coastal communities.