A ‘Miserable Underworld.’ One Washington Mom’s Fight To Change The Mental Health System

Listen

On a recent evening in Vancouver, Washington, more than 80 people gathered at the local affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. They were there for a forum organized by a fledging group of moms whose severely mentally ill children have struggled to get the help they need in Washington state — sometimes with deadly consequences.

“We are all part of a tribe that we have joined whether we wanted to or not,” mother Jerri Clark told the packed room.

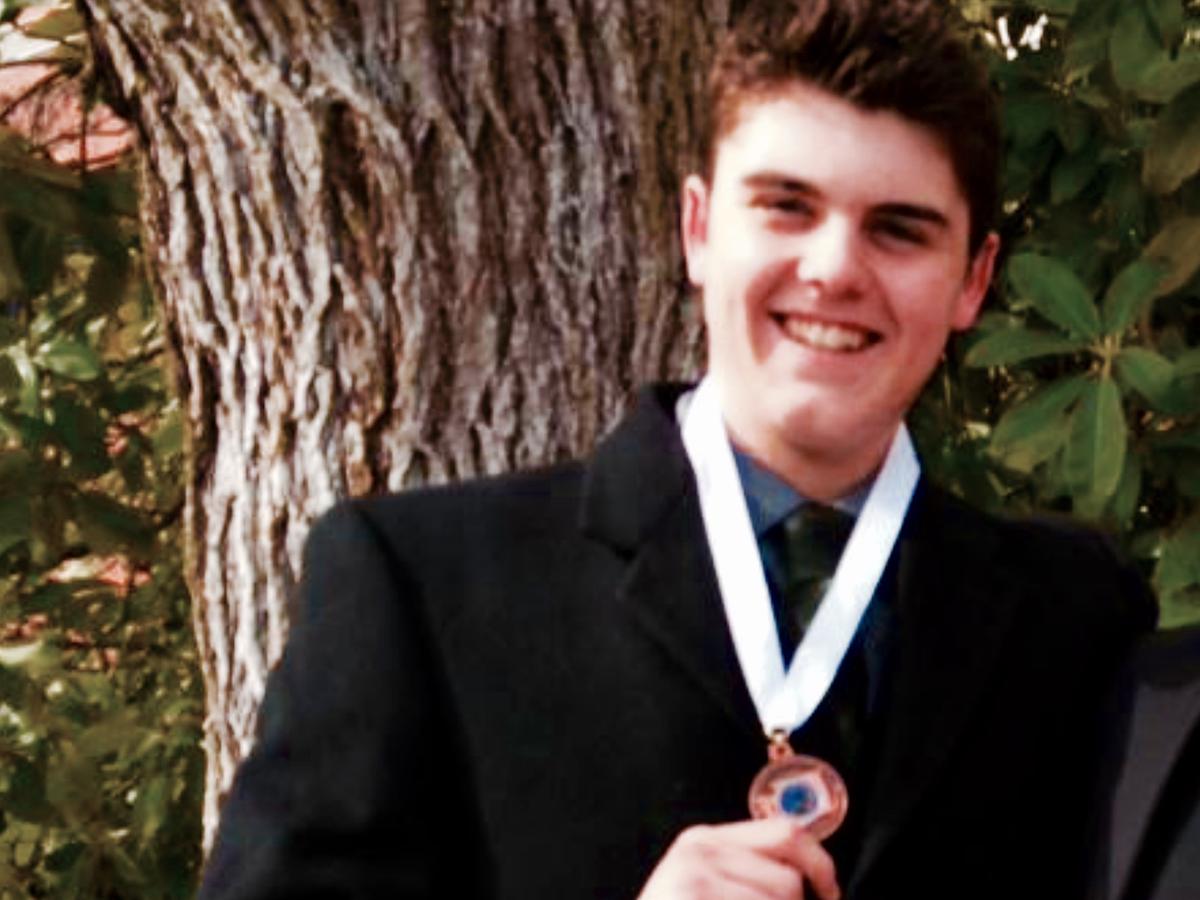

Clark founded the group Mothers of the Mentally Ill (MOMI) last spring after her 22-year-old son Calvin, a former college student and debate scholar, was arrested for allegedly breaking into a home during a mental health crisis.

Over the previous three years, Calvin, who has a severe form of bipolar disorder, has been in and out of jail and mental hospitals. He’s also attempted suicide and been homeless. His behavior got so erratic in January 2017 that Clark took out a protection order against him following an incident at their home where the police were called.

In Clark’s experience, help for her son wasn’t available until he was in such an extreme state of decompensation that he posed an imminent threat to himself or others. At that point, he qualified for involuntary hospitalization under state law.

State law sets a high bar for involuntary commitment because of concerns about civil liberties. But many families say the unintended consequence is their loved ones often end up in jail when what they need is mental health help.

Now, Clark and fellow parents are demanding that Washington politicians change the state’s mental health system.

“Violence is a requirement for care,” Clark said. “Everyone knows this doesn’t make any sense.”

Calvin’s Story

The Clark family’s journey through Washington’s mental health system began in February 2015 when Calvin – who agreed to have his name used for this story – was a freshman at Willamette University and started showing symptoms of bipolar disorder. He moved back home and was soon formally diagnosed.

According to his mother, Calvin was stable for a while, but with limited access to treatment and medication management, he began to cycle between mania and depression.

In January 2016, he was voluntarily hospitalized. After that, Clark devoted herself full time to trying to help Calvin manage his bipolar disorder. At the time, Calvin was on his parents’ private insurance. One of the family’s major frustrations was their inability to access a psychiatrist and establish a long-term care plan for Calvin.

A pattern started to emerge. He would get better, then stop taking his medications and decline again. Clark said her son suffered from anosognosia, a condition characterized as having a lack of insight into one’s illness.

In the fall of 2016, the situation reached a crisis point. Calvin was arrested attempting to climb Haystack Rock in Cannon Beach, Oregon. Soon after he was arrested again in Portland for disorderly conduct. A third arrest came when police found him parked on the side of Interstate 5 where he’d run out of gas.

Then one day in January 2017, Calvin locked his parents out of the house while his mother had guests over. His father, Matt, managed to get into the house where he had an altercation with Calvin. The police were called and arrested his father for domestic violence. The charges were later dropped, but Clark said the arrest sent the family into further crisis. Her husband — who’d never been in trouble with the law — wasn’t allowed in their home because of the pending charge. Calvin couldn’t be in the house either because she had taken a protection order out against him.

Soon after the incident at the house, Calvin was found walking in traffic. He was briefly hospitalized, but then released.

Then on January 28, 2017, Calvin said he was homeless, depressed and hearing voices when he walked to the mid-span of the I-5 bridge over the Columbia River between Vancouver and Portland and jumped.

“I was just like ‘peace out, there’s nothing left in this world for me,’” Calvin explained recently.

As soon as he hit the water, Calvin said he knew he wanted to live. An expert swimmer, he was able to get to shore where rescuers were waiting. After that he spent 10 days in a psychiatric facility and then entered a residential treatment program for a month. Looking back, Calvin said he sees the irony.

“I had to actually attempt to take my own life to even start to get the help that I needed,” Calvin said.

A Turning Point

For a while things stabilized. Calvin got a place to a live and a job in Vancouver. But then, once again, he stopped taking his medications. Calvin ended up homelessness in the Bay Area, then was involuntarily detained for a week after he was found in a state of psychosis. He moved to Seattle, where his parents tried to help him, but his mental health deteriorated again.

Last May, he allegedly tried to break into a home and was arrested again. He spent two months in the King County Jail — most of it spent in solitary confinement.

As her son sat in an isolation cell in the King County jail, Clark contacted Governor Jay Inslee’s office to express her frustration with the state’s mental health system which she calls a “miserable underworld.” The online form she used to request a meeting with the governor asked for the name of the group she represented.

On a whim, Clark wrote “Mothers of the Mentally Ill.”

Soon she was contacted by the governor’s office and a meeting was arranged with Rashi Gupta, Inslee’s policy advisor on mental health. On June 26, Clark brought 17 families from across Washington to Olympia to share their stories with Gupta. The meeting lasted three hours.

“There were a lot of tears and emotion in the room,” Gupta recalled recently.

Gupta said it was unusual to have so many families willing to share stories of how their children struggled with mental illness.

“In the past there’s been a lot of stigma around people speaking up and I think that it is one of the most important things that can happen in this process,” Gupta said.

Clark said families in crisis are sometimes advised by county crisis responders to try to “hack the system” by allowing their child to assault them so they can meet the criteria for services.

But Clark and her fellow parents feel those “hacks” come too little, too late.

Before the meeting, the families met briefly with Inslee who told them that mental health was one of his top priorities for the upcoming 2019 Legislative session. Clark said her group, which includes the families of three young adults who died by suicide, is determined to hold Inslee to his promise.

The group now has a list of recommended policy changes for the state legislature. That list includes a controversial proposal to establish state standards for court-ordered hospitalization based on a person’s “need for treatment” instead of a determination that someone poses an imminent threat to themselves or others.

The ACLU opposes changing this standard for involuntary treatment — though agrees that the system too often ends up placing people in jail instead of in environments where they can get better.

“The ACLU opposes lowering the legal standard for involuntary treatment, because due process requires adequate safeguards for such a significant deprivation of a person’s liberty,” the ACLU’s Nancy Talner said in a statement. As an alternative, Talner said the organization supported “more community-based treatment options.”

Other MOMI recommendations include funding for more psychiatric beds, earlier access to intensive services and case management and prohibiting the release of seriously mentally ill individuals into homelessness.

“We are not going to wait and wait and wait and watch our children die and suffer and struggle because the state can’t figure this out,” Clark said.

Inslee’s office is still formulating its mental health policy agenda and budget for 2019 and did not have specific proposals to share.

A Time For Change

Clark’s timing may prove serendipitous. The state recently agreed to sweeping changes to the mental health system as part of a settlement to an ongoing class-action lawsuit known as the Trueblood case.

The case involved mentally ill inmates languishing in jail while awaiting competency evaluation and restoration services and has resulted in more than $60 million in contempt of court fines against the state of Washington for failing to meet court-ordered timelines.

Under the settlement, which must still be approved by a judge, the state has agreed to fund more crisis response services, jail diversion programs and new training for police and jail staff, as well as additional staff and beds for competency evaluation and restoration services.

Separately, Inslee has called for a major downsizing of Western State Hospital, the state’s largest psychiatric facility. His plan is to move most civil, or non-criminal, patients out of the 857-bed hospital and into new 16-bed facilities located around the state. Western State would then become a “forensic center of excellence” focused on serving psychiatric patients in the criminal justice system.

As for Clark’s timing, it looks like Calvin may finally be moving out of crisis. He’s out of jail now while his defense attorney tries to get his case moved to mental health court. Calvin is participating in a King County program that provides intensive services called the Program with Assertive Community Treatment.

“It’s the most well he’s been in two-and-a-half years,” Clark said. But, she added: “He needed this care at the very beginning.”

In a recent phone interview, Calvin described feeling as if he is “back from the dead.” He now hopes to join his mother in Olympia next January to tell his story before state lawmakers.

Copyright 2018 Northwest News Network

Related Stories:

Voucher program provides free counseling for farmers

Washington State University offers a Farm Stress Counseling Voucher program for farmers. Roni Ryan, pictured, is one of the farmers who has received counseling from the program. (Courtesy: Roni Ryan)

Bills to allow some, regulated access to psilocybin unlikely to move forward

Washington state lawmakers still can’t pass bills to allow for some legal access to psychedelics.

With Feb. 21 as the cutoff for bills to move out of policy committees, two pieces of legislation that would have allowed regulated and supervised access to psilocybin for adults won’t be moving forward — Senate Bill 5201 and House Bill 1433. The bills faced opposition from state psychiatric and medical groups, as well as advocates for psychedelics.

‘It’s a crisis’: How the shortage of counselors is affecting the rural Northwest

In small towns, such as Walla Walla, Washington, behavioral health care providers can be hard to come by. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) watch Listen (Runtime 3:49) Read By Rachel