Washington Sent Brain Injury Patients To Oklahoma — Then All But Forgot About Them

On the evening of August 14, 2010, Steve and Laurie Jenks were returning to their motel from a wedding in Walla Walla. It was dark and Steve, who was driving, had been warned to watch for deer along Highway 124.

Just outside the town of Prescott, Steve said he thought he saw a deer coming out of the ditch onto the two-lane road. As he slammed on the brakes, the car veered across the center line into the path of an oncoming Jeep.

The two vehicles smashed nearly head-on — glass, metal and plastic exploding the quiet summer night.

Everyone survived, but Laurie would never be the same again. She had suffered a severe brain injury that left her in a coma-like state for nearly a month. When Laurie emerged from the coma, her personality had changed — a common effect of traumatic brain injuries. According to Steve, Laurie became erratic, angry and difficult to control. She would yell and swear and also bite, kick and slap.

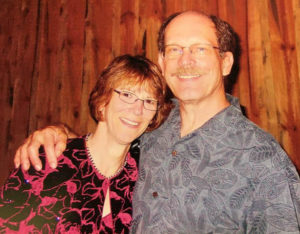

Steve and Laurie Jenks at a wedding in 2010 shortly before a head-on car crash left Laurie severely brain injuried

Courtesy of Steve Jenks

Because of these behaviors, Steve struggled to find care for his wife. He quickly discovered Washington state lacks facilities to treat brain injury victims with behavioral issues — especially those like Laurie who are on Medicaid, the state’s insurance program for the poor and disabled.

By 2015, nearly five years after the accident, Laurie had cycled in and out of several group homes and was placed in a hospital unit where older patients with mental disorders are treated.

Desperate to find Laurie help, Steve heard about a neurologic rehabilitation facility called Brookhaven Hospital two-thousand miles away, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Washington’s Medicaid program, he discovered, would pick up the $1,000 a day tab.

“I really wanted to get her out of hospital, but I didn’t want her halfway across the country either,” Jenks said.

Laurie Jenks was not the first, nor the last Washingtonian to go to Brookhaven. Between 2014 and 2017, Washington’s Medicaid program sent 16 brain injured patients to Oklahoma. In each case, the patient flew by air ambulance at a cost of $230,000 per flight.

But there was one problem. The state didn’t have any plan to get them back.

In fact, once the patients got to Brookhaven they fell between the cracks of two state agencies. As a result, some of them stayed in Oklahoma for years during which time no official from the state’s Medicaid program went to visit them. In the end, what began as hospital-level rehabilitation care morphed into a very expensive form of long-term care. It wasn’t until a doctor at the state’s Medicaid program sounded the alarm that efforts began to bring the patients home.

THE ‘TOTAL PACKAGE’

In 2014, Washington’s Medicaid program had signed a contract with Brookhaven to provide care to hard-to-place brain injury patients.

According to Nancy Hite, a nurse with the Medicaid program, Brookhaven offered a “total package” to help these clients with their neurobehavioral needs. They would get one-to-one care and access to five to six hours a day of therapy.

Jenks was under the impression Laurie would stay at Brookhaven for a few months and then return to Washington more stable and ready for a long-term placement. But months stretched to years. Laurie Jenks is one of three patients from Washington who remain at Brookhaven — although all three are expected to be relocated to other facilities this month.

While at Brookhaven, Jenks said Laurie’s behavior improved. But physically, she declined. When Laurie first got to Brookhaven she could walk with help. Over time, she became confined to a wheelchair.

Several months ago, Jenks said Brookhaven staff informed him they didn’t expect to see any significant progress in Laurie’s condition.

“They’ve told me they’ve given up on trying to do any substantive rehab, they’re just basically trying to keep her from declining, which they’re not really doing all that well,” Jenks said.

Brookhaven CEO Rolf Gainer declined to comment on Laurie Jenks, citing patient privacy, but said it’s common for people with brain injuries to age more quickly.

“They’re going to experience some deterioration in their functional skills at an earlier rate than individuals without a brain injury,” Gainer said.

Jenks isn’t the only relative to question the quality of care at Brookhaven.

NADJA’S STORY

In March 2016, Regina Ibrahim traveled with her then 22-year-old daughter Nadja via air ambulance to Tulsa from Seattle. Like Laurie Jenks, Nadja, who had suffered an infection after brain surgery, had been approved by Washington’s Medicaid program to go to Brookhaven Hospital.

But when they arrived by ambulance at the single story facility in east Tulsa, Ibrahim said she was told she couldn’t accompany Nadja past the front lobby. It was not the welcome she had expected.

“I looked at the lady, I said, ‘Do you really think that I’m going to take my kid some place and drop them off and not see where they’re going to be living? Are you kidding me?’” Ibrahim said.

Gainer, the Brookhaven CEO, said visitors generally are not allowed on to the treatment units for privacy and confidentiality reasons.

Eventually, Ibrahim said, they relented and let her into the locked unit. Ibrahim helped Nadja get settled, filled out some paperwork and met with the director of neurologic rehabilitation. When it was time to say goodbye, Nadja didn’t want her mother to leave.

Regina Ibrahim and her daughter Nadja take a selfie together during a recent visit at Western State Hospital. Courtesy of Regina Ibrahim

“She goes, ‘You can’t leave me here, you can’t,’” Ibrahim recalled in a recent interview. “And I said ‘Nadja.’ I said, ‘I have to leave you here,’ I said, ‘because we have to get you better’ and I left.”

Nadja’s case was complex. Beginning at 19, she’d experienced delusions and been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Later, doctors discovered a benign brain tumor. But after she had surgery to remove it, Nadja developed an infection. Her mother believes that infection caused permanent damage to Nadja’s brain, although she’s never been formally diagnosed with a brain injury.

It was Nadja’s history of hospitalizations and increasingly difficult to manage behaviors that eventually resulted in her going to Brookhaven. Six months after she arrived, Ibrahim returned to Tulsa for a visit. What she found alarmed her.

“It wasn’t the child that I left there, let’s put it that way,” Ibrahim said.

She said Nadja was aggressive and erratic. She would yell expletives and wouldn’t let her mother touch her. “She was like animalistic, in survival mode,” Ibrahim said. “Nadja was not like that before.”

When Ibrahim returned home after visiting Najda, she said she called Washington’s Medicaid program.

“I said, ‘I’m not really sure what’s going on down there,’ I said, ‘But I’m telling you there’s something not right going on down there and I think you guys need to go pay attention to it and look at it,’” Ibrahim said.

QUALITY OF CARE

Brookhaven Hospital describes itself as a “comprehensive mental health center” that serves patients with psychiatric diagnoses, chemical dependency, eating disorders and traumatic brain injury.

The Neurologic Rehabilitation Institute at Brookhaven is an accredited, 36-bed unit in a separate wing of the facility that offers a range of services to severely brain injured patients with “neurobehavioral, psychiatric or substance abuse problems,” according to Brookhaven’s website.

Brookhaven offers its brain injury program to state Medicaid administrators as a solution for the hardest-to-place patients.

“Often, these individuals have long histories of violent and aggressive behaviors,” reads a promotional page on the NRI website. “Many of them have had numerous encounters with law enforcement — or may even be currently incarcerated.”

According to brain injury experts, the best outcomes are achieved when a severely brain injured patient receives inpatient, acute care rehabilitation immediately following their hospitalization for their injury. But Brookhaven targets a different clientele — individuals who are often many years past their injury, but have not been successful in community-based settings.

“The type of patients that we see at [Brookhaven] are unique and there’s a real gap in services for these individuals,” said Gainer, the CEO of Brookhaven, during a May visit to Tacoma to attend the Brain Injury Alliance of Washington annual conference.

Because of patient privacy, Gainer wouldn’t speak directly to the care Regina Ibrahim’s daughter Nadja received at Brookhaven. But he defended his program’s track record, noting that the hospital is required to document all care and services provided and files monthly progress reports on each patient.

Rolf Gainer, Ph.D, the CEO of Brookhaven Hospital, says his facility has a track record of good results with patients and positive ratings with families.

CREDIT: AUSTIN JENKINS

“We provide a very high level of service,” Gainer said. “We have an outcomes study that’s been running for many, many years tracking our outcomes and comparing it to benchmark studies and our outcomes are consistently very, very high.”

Gainer added that Brookhaven earns “high and positive” ratings with families and referral sources.

One person offering praise for Brookhaven: Paul Linnes, whose longtime partner Michael Oakley was the first Medicaid patient from Washington to go to Brookhaven.

In November 2013, Oakley had collapsed at home. Linnes called 911 and began CPR before the paramedics arrived and took over. During the several minutes it took to get his heart beating again, Oakley’s brain was deprived of oxygen resulting in what’s known as a severe anoxic brain injury. As a result, Linnes said Oakley was often disoriented and could be aggressive. Oakley wound up in the hospital because no long-term facility would take him because of his behaviors.

Linnes found Brookhaven Hospital while doing an internet search for neurologic rehabilitation facilities that took Medicaid. And it was Michael Oakley’s case that led Medicaid to meet with Brookhaven representatives, and ultimately sign the contract to send patients there.

Linnes said once Oakley was approved to go to Brookhaven, things moved quickly. In March 2014, Oakley was discharged from the hospital and put on the medical flight to Tulsa with Linnes at his side.

“The hardest day of my life was having to fly home from Tulsa the very first time,” Linnes said.

But he took comfort knowing Oakley was now at a facility where he would get one-on-one care for his brain injury and related behaviors. It didn’t take long to see signs of progress.

“Michael began to thrive,” Linnes said. “He really, really took well to their therapeutic techniques.”

Paul Linnes, left, and his partner Michael Oakley, a patient at Brookhaven Hospital, at a Tulsa, Oklahoma, restaurant they often frequented for lunch.

CREDIT COURTESY OF PAUL LINNES

Oakley stayed at Brookhaven the longest of all the patients — more than three-and-a-half years. He returned home last November after developing serious medical complications related to his injury. In May, six months after returning home to Washington, Oakley died.

“I look at those months as a gift,” Linnes said. “I used to tell him, ‘You’re back home now and I’m so happy you’re closer to home and I get to see you more often and that makes me really happy.’”

Once Washington’s Medicaid program had a contract with Brookhaven, word got out in the brain injury community. One of the people spreading the word was Janet Mott, a clinical case manager on contract with the Brain Injury Alliance of Washington State. Mott said until that point there were few, if any, options for brain injured patients with severe behavior issues. Now there was a place to go.

“People began to say, ‘Oh there is some hope,’” Mott said.

Janet Mott, Ph.D, of the Brain Injury Alliance of Washington, visited Brookhaven Hospital several times and was impressed with the care.

CREDIT AUSTIN JENKINS/NW NEWS NETWORK

Later, Mott became a regular visitor to Brookhaven. In fact, between 2014 and 2017, Mott said she made at least half a dozen trips to Tulsa. She’d become a guardian for one of the Washington patients.

Like Linnes, Mott was impressed with the care.

“I observed staff being respectful and appropriate with the patients and in general people were making progress, but slowly,” Mott said in an interview.

Mott said she didn’t expect the patients from Washington to remain at Brookhaven forever, but she wasn’t alarmed that their stay extended from months to years. “I never anticipated that they’d be back home to the state of Washington quickly,” Mott said. “These were people with multiple needs, complex needs, very severe limitations or deficits.”

If anything, the fact the Washington patients stayed in Oklahoma so long was, from Mott’s perspective, a commentary on the lack of brain injury care back home. “We have a long ways to go to offer the full spectrum of needed services for people with traumatic brain injury in the state,” Mott said.

THE FINAL FIGHT

The final patient to go to Brookhaven departed Washington aboard an air ambulance flight in February 2017. A couple of months later, Dr. Shanna Johnson, a rehabilitation specialist with Washington’s Medicaid program began to look more closely at the Brookhaven patient charts.

“I started seeing things that didn’t make sense to me,” said Johnson, who had recently been promoted into more of an oversight role.

As she studied the patient charts she realized most of the patients were receiving one-to-one care and were scheduled for multiple hours of therapy per day.

“So then I started being like, ‘Why are we sending these chronic patients to acute, inpatient rehab in another state?’” Johnson said.

As Johnson continued to review the patient charts she discovered something else.

“Nobody was ever being discharged, and there was no discharge plan,” Johnson said.

That’s when Johnson said she realized the state had a problem.

As she explained in a March email to her bosses, “There is no process for discharging post-acute patients … which is resulting in length of stays months longer than necessary which is driving up the cost of care at this facility.”

Johnson noted that the state was paying Brookhaven $1,000 a day, per patient while a skilled nursing facility back home would cost $200 a day.

It turned out, the patients at Brookhaven had slipped between the cracks of two massive state agencies—Washington’s Health Care Authority, which runs the Medicaid program, and the Department of Social and Health Services which manages long-term care.

In the end, it cost Washington’s Medicaid program more than $12 million to send the patients to Brookhaven.

By summer of 2017, getting the 11 remaining patients at Brookhaven back home to Washington had become a top priority at both agencies. But it wasn’t going to happen overnight.

That July, there was growing concern within the Health Care Authority about how long it was taking to develop a discharge plan.

“[T]his is money we should not be spending,” wrote a Medicaid official in an email obtained through a public records request. “What can we do to move this along?”

At the Department of Social and Health Services, the job of finding placements in Washington for the Brookhaven 11 had fallen to Betsy Jansen, a program manager in the Aging and Long-Term Support Administration who had a background in working with brain injury clients.

“My first reaction was surprise,” Jansen said of learning the state had 11 patients at Brookhaven. “And then my second was, ‘Why do we need to send people out of the state of Washington?’”

Betsy Jansen of the Department of Social and Health Services was given the job of bringing home the remaining 11 patients at Brookhaven Hospital in Tulsa.

CREDIT AUSTIN JENKINS/NW NEWS NETWORK

The first thing Jansen did was contact the families and guardians of the patients.

“Everybody wanted their loved one to come home, but didn’t quite know how to make that happen,” Jansen said.

In August of last year, Jansen and a colleague flew to Tulsa to evaluate all of the patients to find out what their needs were.

As the first state official to lay eyes on Brookhaven, Jansen said her impression was that it felt institutional. She noted that the patients had to be escorted in and out of the locked units. But she said the staff was helpful and she and he colleague were well received as visitors.

“I did not have any concerns at the time at all of what I saw or what I heard,” Jansen said.

After she returned to Washington, Jansen began the arduous process of trying to find long-term placements for the Brookhaven patients. As had been the case when the patients first went to Brookhaven, good options were few and far between.

Now, a year later, Jansen said she’s been able to bring eight of the 11 patients back to Washington.

“I’m really glad that we can bring people home and serve them here,” Jansen said. “That was my primary goal and mission and we’re in the process of doing that and I feel really proud of that work.”

According to Jansen, four of the eight have gone into one of two adult family homes that specialize in managing difficult behaviors. Another patient was discharged back into the community, but with support from the Developmental Disabilities Administration.

Regina Ibrahim’s daughter Nadja returned to Washington in January. She immediately went into Harborview Medical Center’s psychiatric unit. In May, she was moved to Western State Hospital—the state’s largest mental hospital. Her mom is trying to open a group home in southwest Washington to care for brain injured patients, including her daughter.

Steve Jenks’ wife Laurie is one of the three patients still at Brookhaven after he rejected the state’s plan to put her in an adult family home in Spokane. Since then, he’s been looking for long-term care facilities in the Northeast where his daughter lives. In a recent email, he said he was days away from getting Laurie moved to a nursing home in Massachusetts.

LESSONS LEARNED

The return of the Brookhaven patients signals the end of an unsettling chapter in the story of brain injury care for Medicaid clients in Washington state. Patients were moved thousands of miles away from their families and placed in a locked-down facility, some for years. While they were there, the state didn’t have the systems in place to adequately monitor their care and progress. And there was no plan or mechanism in place to eventually bring them home.

“It’s just crazy,” said Dr. Kathleen Bell, a brain injury rehabilitation specialist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center upon hearing about the Brookhaven patients. “Somebody obviously lost track of what was going on.”

Previously, Bell was the medical director of the Brain Injury Rehabilitation Program at the University of Washington. While she couldn’t comment specifically on the decision to send Medicaid patients from Washington to Brookhaven, she could see how it happened.

“Washington state has never had a good system for taking care of people with severe behavioral problems,” Bell said.

That was the gap Brookhaven filled.

But this past March, more information about Brookhaven’s quality of care came to light. The Oklahoma Department of Health conducted an unannounced inspection of Brookhaven Hospital and found serious deficiencies regarding patient rights, nursing care and quality performance.

In one instance, the report found that Brookhaven’s failure to maintain an ongoing quality improvement program may have resulted in delayed “care decisions” for a 34-year-old patient who died unexpectedly in February of this year. That patient was in Brookhaven’s behavioral health unit, not the neurologic unit.

In an interview, Gainer said he was confident the issues identified in the report had been addressed and that the hospital would pass its next inspection.

Gainer stood by the care the Washington patients received at his hospital and said their length of stay was not unusual for his program.

“We served patients, we provided the services they needed,” Gainer said. “I wish there were community services that we could have moved them into at an earlier time.”

Copyright 2018 Northwest News Network

Related Stories:

COVID-19, 5 years later: Reflections on the scars we carry, and resilience in unprecedented times

NWPB caught up with local residents and doctors to talk about how they’ve moved forward following the COVID-19 pandemic. They spoke about how the experience changed them and wisdom they’ve gleaned along the way. These are their reflections.

Religious freedom vs. health care access: How faith influences health care in Washington and Idaho

Religion can sometimes impact health care access in places like Washington and Idaho. (Credit: Unsplash / Hush Jade Photography) Read By Emma Maple | FāVS News The Idaho state Legislature

Community connection helps women heal from trauma, addiction in Eastern WA

NAOMI volunteers create community with women working to overcome trauma. (Credit: NAOMI) Read By Rose Owens, FāVS News About 95% of people struggling with addiction have experienced trauma, according to