China’s Marriage Rate Plummets As Women Choose To Stay Single Longer

PHOTO- At Shanghai’s weekly “marriage market,” parents advertise their unmarried adult children with signs taped to umbrellas. Chinese parents and the government are doing what they can to reverse the trend of falling marriage rates. The sign above the entrance reads: “Comprehensively manage the marriage market, maintain the order of the park together.” CREDIT: NPR

BY ROB SCHMITZ

At a downtown market in Shanghai, people are hustling to sell their goods. But at this market shaded by trees lining the pathways of People’s Park, their goods are their grown children.

“Born in 1985, studied in the U.K., she’s short, has a Shanghai residence permit, owns her own apartment,” says Mrs. Wang, reading aloud the sign she’s taped to an umbrella advertising her unmarried daughter. It’s one of hundreds of umbrellas lined up along the park’s walkways with similar signs.

Mrs. Wang, who refuses to give her full name to protect her daughter’s identity, has come to Shanghai’s “marriage market” each weekend for the past three months to try and find a suitable husband for her daughter.

“She doesn’t agree with what I’m doing,” says Wang, “but she respects her parents’ wishes. Young people these days don’t care about marriage. They don’t pay enough attention to our traditional values. Their views are becoming more Western.”

Wang blames her 33-year-old daughter’s single status on the seven years she spent in the U.K., where Wang says her daughter “became more independent.” But there are other reasons — apart from Western influence — why China’s marriage rate has plummeted by nearly 30 percent in the past five years.

Dai Xuan, 30, works as the editor of a luxury magazine in Shanghai and says her own reasons are economic. “Before, in China, you married to survive,” she says. “Now I’m living well by myself, so I have higher expectations in marriage.”

Like many young, urban Chinese, Dai studied abroad – she lived in Norway – and enjoys her job. She says she’s not in a rush to get married.

Dai Xuan, 30, who works as the editor of a luxury magazine in Shanghai — and is pictured at the helm of a private jet — says the reason why she hasn’t married yet is economic. She says she loves her job and she makes more than enough to support herself, which has made her pickier about dating.

NPR

“People my age laugh at those who get married early, because only rural people without an education do that,” says Dai. “It’s not that successful women don’t want to marry, it’s that making money makes us pickier.”

But that can work both ways, says Josephine Pan, the 45-year-old Shanghai CEO of FCB, an advertising firm. In a traditional society like China’s, she says, men are intimidated by her title.

“They don’t want a female CEO as a girlfriend or wife,” says Pan. “Maybe they feel it’s a big threat to them. I’m not an arrogant person, like all the time showing off my title. I keep it very low profile. But no matter how low of a profile you keep, you keep intimidating them.”

While men outnumber women among China’s overall population, at Chinese universities, women have outnumbered men for the past two decades. That means more women have career trajectories they don’t want to jeopardize by marrying and having children while they’re in their 20s and 30s. They’re marrying later, or not at all.

“What’s happening on the ground with these particularly urban, educated women is completely at odds with what the Chinese government wants the women to be doing,” says Leta Hong Fincher, author of the forthcoming book Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China.

Hong Fincher says China’s Communist Party has tried propaganda campaigns, matchmaking events, and even ended the decades-old one-child policy in 2016 to persuade educated young women to marry and start families. But declining birthrates show none of this is working.

The party’s problem boils down to changing demographics. Official projections show that by 2030, there will be more Chinese over the age of 65 than under the age of 14. For the first time in a century, China will be facing a shortage of workers and an oversupply of nonworking seniors, an economic problem that Hong Fincher says will become a political one.

“It relates ultimately to the survival of the Communist Party,” she says. “How do they continue exerting control when you have all these chaotic forces, young people, young women in particular, who are all wanting to do their own thing rather than follow the dictates of the government and marry early and have babies?”

And it’s not only women who are opting to postpone marriage. Yuan Ruiyu, 26, says he and his friends are under pressure from both the government and their parents to hurry up and marry, and it’s having the opposite effect. It’s making them question why they should marry in the first place.

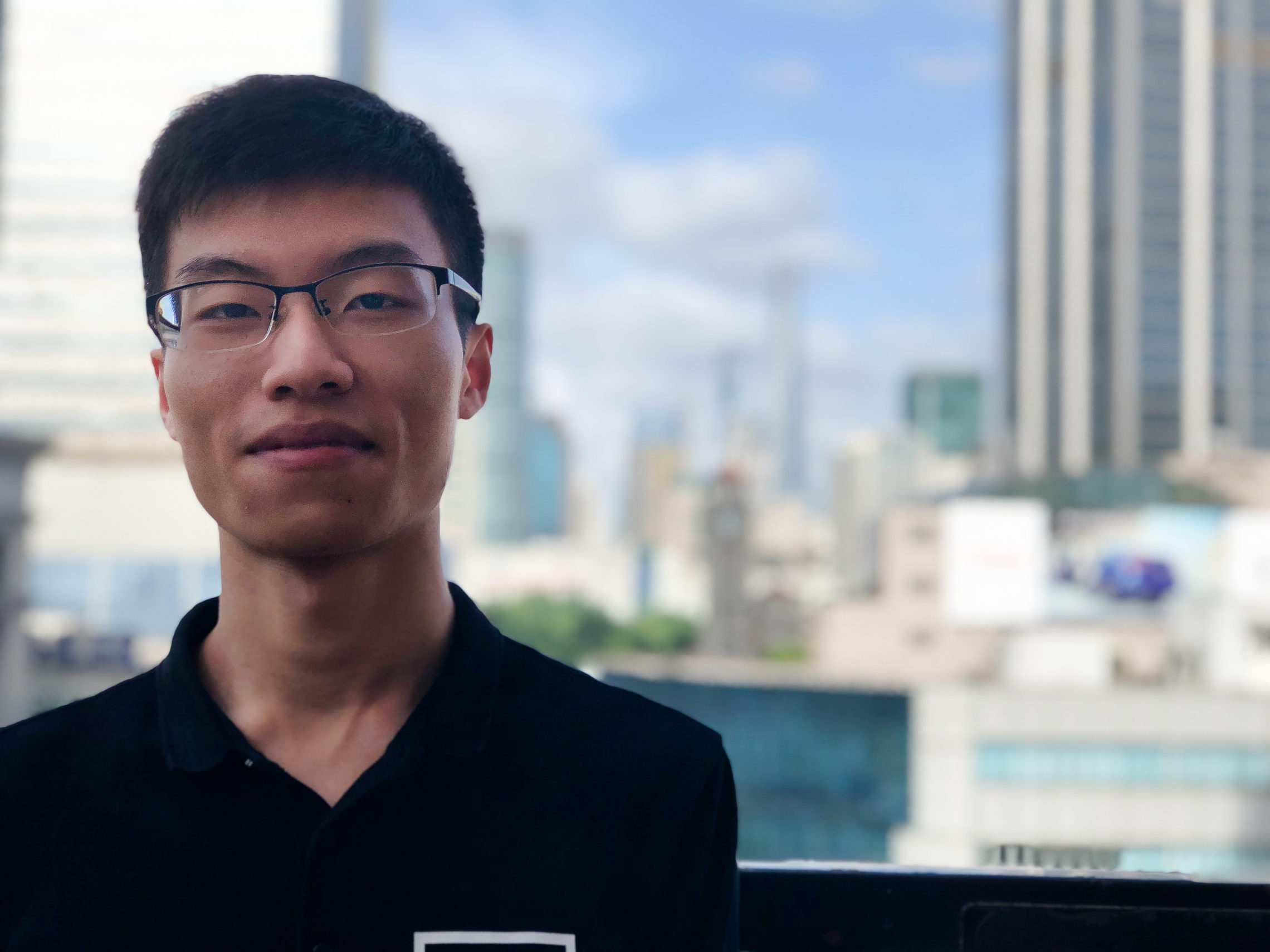

Yuan Ruiyu, 26, says he and his friends are under pressure from both the government and their parents to hurry up and marry, and it’s having the opposite effect on them. CREDIT: NPR

“In China,” he says, “young people are supposed to do as they’re told by their parents and their government. You’re supposed to believe that our country is the greatest and that we should listen to the government and our parents, but it’s all propaganda, and it’s a trap. It’s not for our own good, but for theirs.”

Yuan says as more and more of his peers leave their hometowns, study abroad and find jobs they like, they become more and more independent – and marriage, one of the most personal decisions someone can make, becomes their own decision, not anyone else’s.