How ‘The Battle Hymn Of The Republic’ Became An Anthem For Every Cause

Listen

BY ANDREW LIMBONG

This week, NPR inaugurates a new series called American Anthem, exploring songs that tap into the collective emotions of listeners and performers around an issue or belief. Find more stories at NPR.org/anthem.

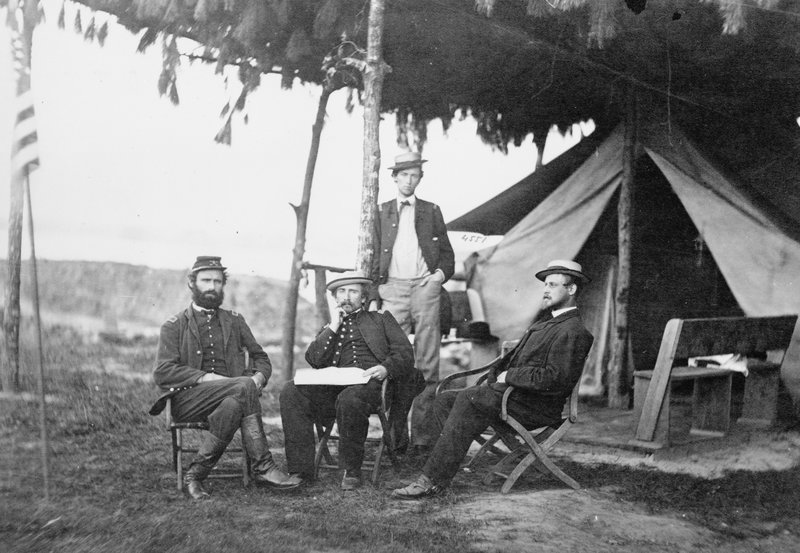

There’s an episode of The Johnny Cash Show from 1969 where the man himself makes a little speech with a pretty big error. “Here’s a song that was reportedly sung by both sides in the Civil War,” Cash says, guitar in hand, to kick off a performance of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The real history on that point is clear: Julia Ward Howe wrote the song as a pro-Union, anti-slavery anthem. But then Cash goes on to say, ” …. which proves to me that a song can belong to all of us.” And about that, he’s right.

I should go easy on Cash for flubbing the history; I had it wrong, too. I didn’t even know the “Battle Hymn” had ties to the Civil War up until recently, because I — and maybe you, if you grew up with a similar flavor of Christianity — only sang it in church. Little did I know the song, with its refrain of “Glory, glory, hallelujah,” had been used to root for college football teams, or as an anthem for labor unions. Evangelist Billy Graham, who helped popularize the song among Christians, even took it to the Russian army chorus in 1992.

“It’s a good march,” says Sparky Rucker. A folk singer and historian who performs a show of Civil War music with his wife, Rucker says the “Battle Hymn” rallies with its rhythm: “It’s just the right cadence to march along, if you’re marching at a picket line or marching down the street carrying signs. … It really gets your blood going [so] that you can slay dragons.”

Dragons are relative, however. Anita Bryant, the singer and conservative activist, used to perform the song at anti-gay rallies. During the 1964 presidential race, Republican nominee Barry Goldwater had to disown a campaign film that posed the election as a choice between two Americas — an “ideal” America, where the tune of the “Battle Hymn” scored images of the founders and the Constitution, and a “nightmare” America, featuring black people protesting and kids dancing to rock music.

On the flipside, the day before he was killed in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. made his famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, which he ended by quoting the song’s first line: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” His home church, Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist, took up the song after his death as an anthem to him and the civil rights movement.

“How people relate to patriotism is kind of how they come into the ‘Battle Hymn,’ ” says professor Brigitta Johnson, an ethnomusicologist at the University of South Carolina who teaches in the schools of Music and African-American Studies. “For example, your white nationalists digging deep into heavy patriotism messages — they bring up things like ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ and the ‘Battle Hymn’ and it becomes their battle cry, just as easily as it could become the battle cry for Ebenezer in Atlanta.”

In other words, Johnson says, this anthem is all about what you bring to it. And in fact, that flexibility is part of its design.

To be clear, he’s not talking about the famous abolitionist, who was executed before the war even began; this John Brown was just a regular soldier. Stauffer, who co-authored the book The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song that Marches On, says the soldiers were making up new lyrics to the tune of an old hymn, “Say Brothers, Will You Meet Us.”

“So when they start making up songs to pass the time, comrades needle him and say, ‘You can’t be John Brown — John Brown’s dead.’ And then another soldier would add, ‘His body’s moulderin’ in the grave,’ ” Stauffer explains. Though their impromptu rewrite was inspired by a regular soldier, the ghost of the abolitionist loomed large — and a marching song called “John Brown’s Body” was born.

“John Brown’s Body” became super-popular among Union soldiers for a few reasons. For one, the simplicity of the lyrics and melody made it easy to sing, and to remember. More importantly, it glorified the righteous fight against slavery. African-American units picked up the melody and added their own spin: “We’re done with hoeing cotton, we’re done with hoeing corn / We’re colored Yankee soldiers just as sure as you were born.”

A few years later, a well-to-do, highly educated poet from New York named Julia Ward Howe came to Washington, D.C. with her minister to visit Union troops. As they did so, Confederates attacked — but the Union soldiers defended, and impressed Howe. Her minister, Stauffer says, pushed her to rewrite the song they’d been singing — “rewrite it and elevate it. Make that song richer for a kind of educated audience.”

Stauffer says Howe wasn’t necessarily looking to write an anthem; she was keen to make the kind of capital-A art that would put her in the ranks of the more respected authors of her time. “Hawthorne, Melville, Emerson, Thoreau — part of the way they were understood as great writers was their use of symbolism,” he says. For Howe’s version of the song, she ditched many of the lines that had been crowdsourced among the troops — such as “Let’s hang Jeff Davis from a sour apple tree.”

Reborn as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Howe’s version is the one we know best today. But it’s worth noting that the troops’ contributions were what made the song so popular in the first place — that, and the stirring melody of the original hymn.

Sparky Rucker says that when he performs the black Union soldiers’ version of the song — even in the South, where, in his words, “the wounds of the Civil War are still fresh” — everyone sings along: “Even my un-Reconstructed Southerners in the audience will sing along with me — ’cause we’ve also sung some of their songs.”

WATCH: Sparky Rucker and his wife Rhonda perform a medley of the various incarnations of the “Battle Hymn,” from the original religious song to the version sung by black Union soldiers.

Rucker says his audiences also sing the Howe version, which eventually won — getting published by The Atlantic in 1862 and becoming canonized. And while it does transcend centuries and cultures, Birgitta Johnson is quick to point out that the “Battle Hymn” is, at the end of the day, a war song.

“The kumbaya moment will not be happening across the aisles because of this song,” she says, “because it’s really about supporting whatever your perspective is — about freedom or liberation, and having God as the person who’s ordaining what we’re doing. And ‘glory, hallelujah’ about that.”

As Johnny Cash said in 1969, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” is an anthem that belongs to everybody. But what really matters is what they’re singing it for.

Editor Daoud Tyler-Ameen contributed to the digital version of this story.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit npr.org

Related Stories:

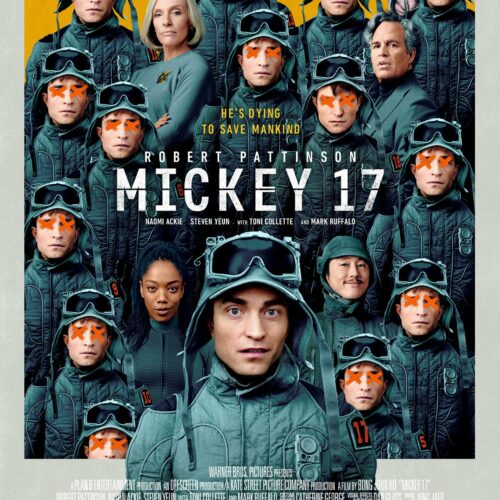

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Love Hurts

Ah, yes, “the things we do for love.” With all due respect to the British band 10cc, which had a hit with that song back in 1976, the new film from first-time director Jonathan Eusebio demonstrates that not all things leave the best impression.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.