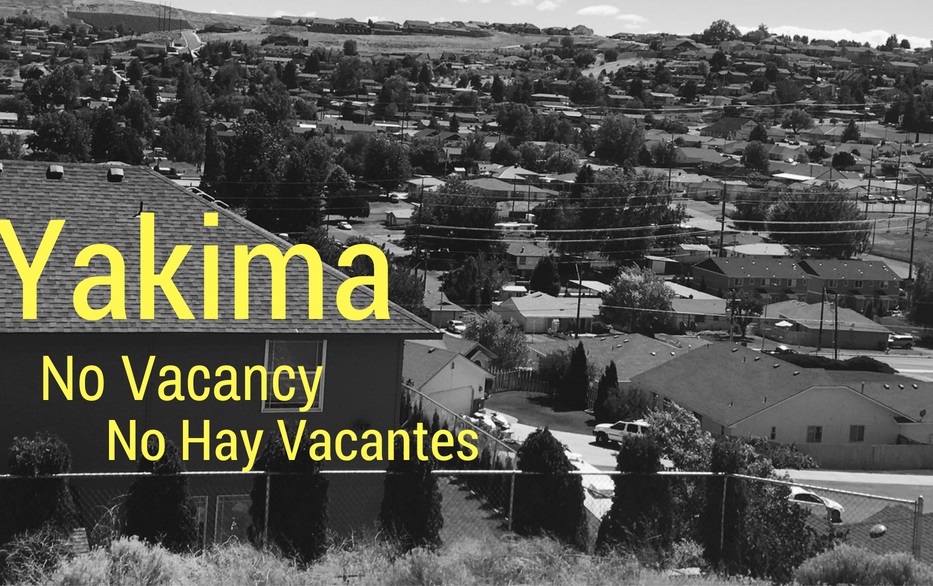

In Central Washington, Housing Crunch Exacerbated By Need For Foreign Farm Labor

Listen

The Northwest is experiencing an affordable housing crunch. And it’s not concentrated in just the largest metro areas like Portland, Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia.

In Yakima, limited housing is coupled with a labor shortage in farm country, leaving farmers wondering: When workers do come, where do you house them?

Here in sunny and agriculturally rich Central Washington, the largest farmworker complex in the state opened in Yakima this month. The revamped FairBridge hotel now hosts 800 beds for temporary farm workers.

As it opens, critics think it may set a dangerous precedent: Other farmers might start buying up area housing for their own workers.

It’s a strange tug of war. Yakima needs more housing and more workers. But it’s short on both.

Housing Shortage

According to the latest numbers from the University of Washington, the county vacancy rate for apartments sits at 0.8 percent,

the second lowest vacancy rate in the state. Housing markets are generally considered full at five percent, and three percent is a sign of a full-on housing shortage.

While the affordable housing struggle is no surprise, it does hit hard in Yakima County where one in five residents is in poverty and wealth is largely concentrated in the western, whiter districts of the city.

And as for the labor shortage: how did that happen? It’s been a growing trend over the last few years as local workers are becoming harder to find.

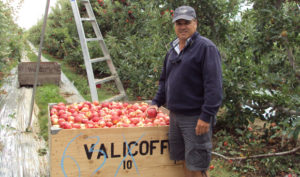

Rob Valicoff, a farmer and co-owner of the new FairBridge farmworker complex, thinks it’s a generational thing.

Rob Valicoff, a Yakima-area orchardist and farmer is backing the largest farmworker housing complex in the state. Courtesy of Valicoff Farms

“Generations have moved on to other jobs,” Valicoff says. “This is America. You’re moving up the ladder. They’ve gravitated to something better for their life.”

That’s where temporary ag workers come in. Known as H-2A employees, these are the people now filling thousands of farm jobs across the Northwest and entire country. The H-2A program is a relic of the Bracero Program that brought Mexican labor in the 80s. Farmers apply to contract foreign workers through the federal Department of Labor. These H-2A laborers come for months at a time to support Washington farmers, especially with the sweet cherry and apple harvests.

Many Requests From Washington Farmers

This year, the U.S. Department of Labor received over 22,000 temporary worker requests from Washington farmers. They aren’t required to report how many workers they actually employed, just how many they applied for in each work contract. But just four years ago, that number was less than half with 10,000 H-2A workers certified to work in the state.

In that time, Washington went from being one of the top 10 states to recruit temporary workers, to now being number two in the nation.

All these labor contracts come with paperwork and state and federal regulations through the U.S Department of Labor and Washington’s Employment Security Department. Workers must be housed and transported to the farm and back. They also have to be fed, and their round-trip transportation from their home countries must be covered by the employers.

That’s great for farmers and for the foreign workers who make higher wages than they would in their home countries. But it causes tensions with local farmworkers who live in the U.S. year-round.

(To clarify, local farmworkers are sometimes also called migrant workers. They follow the harvest, but live in the U.S. permanently, sometimes with or without proper documentation. On the other hand, H-2A workers are legally hired through a federal program for less than a year and then return to their home countries.)

Yakima city councilmember Dulce Gutierrez is skeptical of the effort to house farmworkers in the city.

“It’s misleading to say this effort to put H-2A housing in the city limits of Yakima is about providing dignified housing for farmworkers,” she says. “This is about the bottom line. This is about saving the ranchers money. Some are forward about that, some are not.”

Gutierrez worries farmers will displace local residents by buying up housing complexes to house their own H-2A workers. She’s pushing to create stricter city policies to limit that impact and asked city officials to define the terms “hotel” and “motel.”

Yakima council member Dulce Gutierrez, center, is skeptical of the development to house farmworkers in the city due to the strain on affordable housing. CREDIT: ERIN LODI/UW COLUMNS MAGAZINE

Because the city lacked those definitions, Rob Valicoff and a human resources company called Wafla that recruits foreign workers to the state were able to flip the FairBridge Hotel into housing for workers, all technically within city code.

Gutierrez points out that H-2A workers wouldn’t be covered under the Landlord Tenant Act and that the City of Yakima doesn’t have a rent control policy in place.

All these factors could lead to a precarious situation for local renters.

“The easiest route to gentrifying any neighborhood would be to first remove the long term residents who have commitments to those neighborhoods and replace them with people who don’t,” Gutierrez says.

Valicoff, the fruit grower and owner of the complex, doesn’t think that will happen.

“I don’t think that will displace anyone because there’s no one here,” he says. “If it was apartments or houses, then I would say it could affect it somewhat.”

While that dynamic plays out, FairBridge is welcoming the first wave of H-2A workers this month.

Soon, hundreds more will join them in the complex and thousands more around the state.

Copyright 2018 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

These churches offer shelter and sanctuary to vulnerable migrants. Here’s why

Bishop Joseph Tyson (left) and the Rev. Jesús Mariscal (right) of the Yakima Diocese worry about how their parishioners will cope with broad changes to immigration policy, which have had

Landfill neighbors worry about PFAs contamination seeping into drinking water

A view of the landfill from Carole Degrave’s property line. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 0:54) Read For years, some people who live near a Central Washington landfill

Dozens in Yakima rally to support science for national protest

Around 50 people gathered for Yakima’s Stand Up for Science rally on Friday. People around the country attended science protests at the same time. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB) Listen