Plants In Space: Not Your Average Garden Variety Cosmos Exploration

Listen

When you think of space, what comes to mind? It’s probably cold, dark, with things floating around inside a sterile, metallic ship.

One Northwest researcher is focused on the sustainability of creating a little greenery in the great vacuum of the cosmos. Why? Because with long-term space travel becoming more within reach, astronauts will need to grow food to sustain themselves through long-term travel, and on colonies.

“Without plants, we’re not here.”

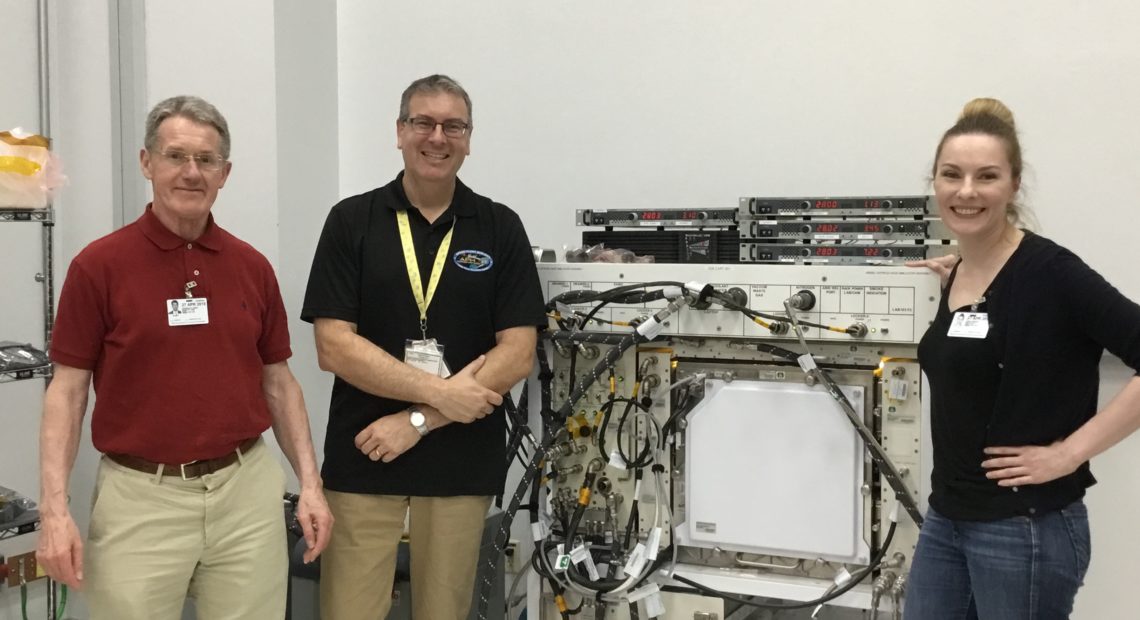

Dr. Norman Lewis, researching at Washington State University has been working with NASA for a long time on this project. The recent launch is a culmination of decades of collaboration and research.

His research was launched in May, 2018 and in early June the plants begin to grow in the Advanced Plant Habitat on the International Space Station.

It is regarded as a “major advance” in space-plant research.

Dr. Norman Lewis came to the Northwest in Vancouver, B.C. originally for his PhD at the University of British Columbia, then Cambridge, then back to Canada with part of McGill University. Then by way of Virginia Tech, he landed back in the Northwest in Pullman, Washington in 1990 to become the Director of the institute of Biological Chemistry at Washington State University until 2014.

He talks with Northwest Public Broadcasting about the research and his thoughts on the history and future of space exploration.

Related Stories:

Richland Lego robotics team hopes state grants won’t be put on hold

Fourth grader Sergio Preciado shows off a Lego shipwreck he helped build and code with his FIRST Lego League team, called the Dino Nuggys. The program is mostly grant funded

Dozens in Yakima rally to support science for national protest

Around 50 people gathered for Yakima’s Stand Up for Science rally on Friday. People around the country attended science protests at the same time. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB) Listen

Whale, ship collisions around the globe could be helped by slower speeds, study shows

A humpback whale breeches off Half Moon Bay, Calif., in 2017. (Credit: Eric Risberg / AP) Listen (Runtime 1:06) Read Giant ships that transport everything from coffee cups to clothes