The Bernstein Centennial Year: Every Score Has Its Story

Leonard Bernstein loved the stories behind the music he conducted, and insisted that every story has a moral. As one of his proteges, Marin Alsop, puts it: “He was unrelenting in his dedication and doggedly devoted to uncovering the composer’s true intent…Every composer spends his life trying to articulate his own personal story and answer those existential questions that are so consuming for him.”

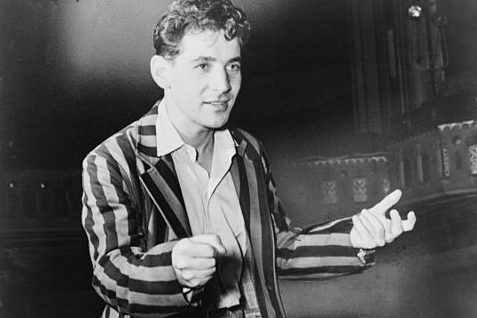

As a young man, Bernstein discovered many specific sources of inspiration. In January, 1937 the eighteen-year-old attended a Boston Symphony concert led by Dimitri Mitropoulos. He “went bananas” over the Greek conductor’s intense engagement with the music and the orchestra, and his flamboyant style. When Mitropoulos heard Bernstein at the piano the very next day, he invited the Harvard sophomore to attend his BSO rehearsals and performances for the rest of the week. Bernstein was mightily impressed by Mitropoulos’ magnetism on the podium, and was by the power of the conductor and the accolades he received in that role. After all, Bernstein at a young age he was prepared to embrace the spotlight

Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960) CREDIT: Fournier-Pouyet

Mitropoulos later wired Bernstein 200 dollars so that he could spend winter vacation in Minneapolis where they could work with that orchestra that Mitropoulos was Principal Conductor. Back at Harvard, Lenny declared that music would be his calling in life.

After graduation, he made the important acquaintance of Serge Koussevitsky. A native of Russia and an exile from the Soviet Union, who made his name as a double bass virtuoso, then began a 25-year tenure as Music Director of the Boston Symphony. During that period, he founded the influential Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood in Massachusetts and Bernstein was one of the first five students accepted into Koussevitsky’s master class in conducting there.

Serge Koussevitsky (1874-1951) CREDIT: George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress

Many years later, Bernstein expressed his admiration for his Russian mentor, saying all that Koussevitsky did “was marshalled and harnessed to be at the service of music. The difference lies between the conductor who is vain on his own behalf and the conductor whose ego glories in the reflected radiance of musical creativity.” Koussevitsky emphasized to the young Bernstein the need to be meticulous in his approach to the music and dedicated to artistic service to the community. Bernstein readily embraced the Russian’s vision: Integrity, warmth of interpretation and insistence on communicating the “central line” in any composer’s score. In other words, identify the music’s story and share it with the audience.

For all that, Bernstein did not accept all of Koussevitsky’s suggestions. He did not change his name to “Leonard S. Burns.” He did not convert to Christianity, as Koussevitsky had done. And he refused to abandon his work on Broadway, which had begun so spectacularly with On the Town in 1944. The two men remained close, however. Bernstein stayed at Koussevitsky’s bedside through the final night of his mentor’s life. He assumed the directorship at Tanglewood. He wore one of Koussevitsky’s suits at his wedding, and he wore a pair of cufflinks given to him by Koussevitsky while conducting for the rest of his own career.

Stay tuned for more installments about the life and legacy of Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990).

Related Stories:

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Maria

“Maria Callas was someone that as she was singing, she was dying every time. Life was taken from her while she sang.” The Chilean writer-director Pablo Larrain has a fascination with mortality. The manifestations of it course throughout his work. In many respects, it inspires his art.