Scientists Push Plan To Change How Researchers Define Alzheimer’s

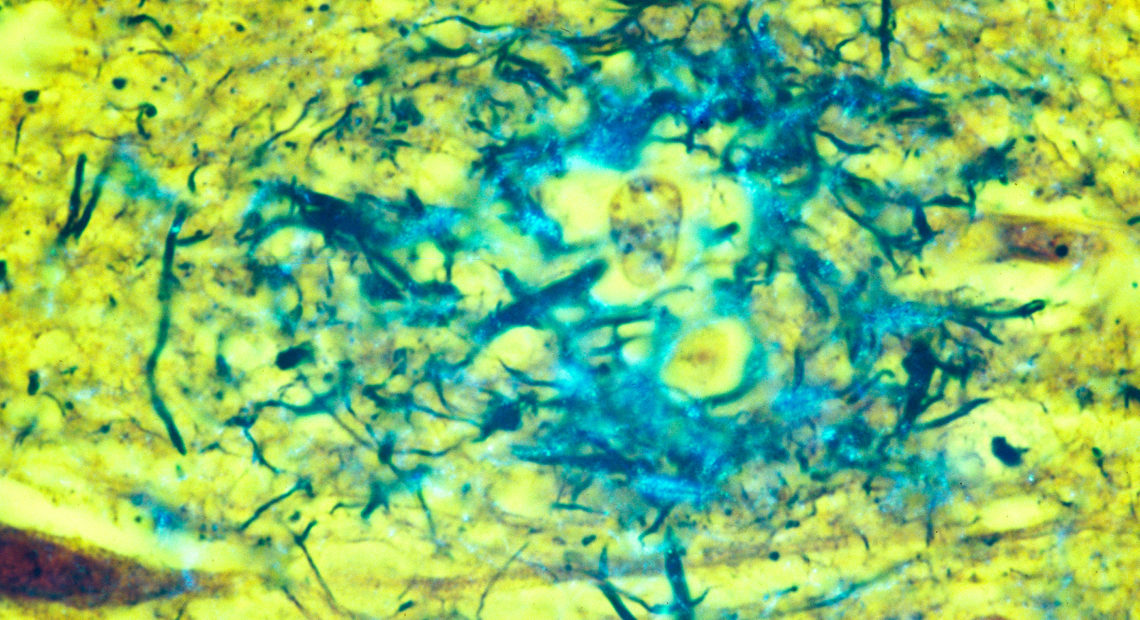

PHOTO- Plaques located in the gray matter of the brain are key indicators of Alzheimer’s disease. CREDIT: CECIL FOX

BY JON HAMILTON

An international coalition of brain researchers is suggesting a new way of looking at Alzheimer’s.

Instead of defining the disease through symptoms like memory problems or fuzzy thinking, the scientists want to focus on biological changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s. These include the plaques and tangles that build up in the brains of people with the disease.

But they say the new approach is intended only for research studies and isn’t yet ready for use by most doctors who treat Alzheimer’s patients.

If the new approach is widely adopted, it would help researchers study patients whose brain function is still normal, but who are likely to develop dementia caused by Alzheimer’s.

“There is a stage of the disease where there are no symptoms and we need to have some sort of a marker,” says Eliezer Masliah, who directs the Division of Neuroscience at the National Institute on Aging.

The new approach would be a dramatic departure from the traditional way of looking at Alzheimer’s, says Clifford Jack, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Mayo Clinic Rochester.

In the past, “a person displayed a certain set of signs and symptoms and it was expected that they had Alzheimer’s pathology,” says Jack, who is the first author of the central paper describing the proposed new “research framework.”

But researchers began to see the flaws in that approach when they took a close look at the brains of people receiving experimental drugs for the disease, Jack says. “About 30 percent of people who met all the appropriate clinical criteria did not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

Their memory or thinking problems were being caused by something else.

So researchers have been looking for more reliable ways of determining whether someone really has Alzheimer’s. And they’ve focused on the two best-known brain changes associated with the disease.

“What we’re seeing now is that Alzheimer’s disease is defined by the presence of plaques and tangles in your brain,” Jack says. And in this way of thinking, he says, “symptoms become the result of the disease, not the definition of the disease.”

Once it was virtually impossible to detect plaques and tangles in a living person. But over time, scientists have developed a number of ways to spot the abnormalities using special brain scans or tests of spinal fluid.

These tests for what are known as biomarkers of Alzheimer’s are allowing scientists to do experiments that would have been impossible relying on symptoms alone. “One could, let’s say, start preventive treatment five years before the onset of the symptoms,” Masliah says.

The new approach has detractors, who argue that it’s not yet a reliable replacement for clinical symptoms in research. And proponents have responded to these complaints by including symptom measures in their proposal, and acknowledging that biomarkers are still in an early stage of development.

Proponents have also stressed that the biomarker approach is not yet the right tool for most doctors who treat Alzheimer’s patients.

“It’s a research framework meant to be tested, a tool for researchers, not for the doctor’s office,” says Maria Carrillo, chief scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Association.

But Carrillo hopes that when drugs to prevent Alzheimer’s finally arrive, biomarker tests can show who should get them.

The proposal, and several commentaries supporting it, appears Tuesday in the April 2018 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.