How Three Major Fires Reshaped Washington’s Cities

It was a beautiful spring for Washington in 1889. Consistently warm temperatures. Almost no rain for the rapidly-expanding territory. Washington was only a few months from its statehood, which would come in November. That fast expansion meant densely-packed cities built hastily from wood. Wooden cities in a dry summer.

When they burned, they burned hot and fast.

The small town of Cheney was first that year. It burned in April. A general store caught fire. The town’s single fire hose had been sabotaged: plugged with the handle of a chisel. The hose burst, leaving the city to form a bucket chain. It wasn’t enough, and the fire consumed much of the town.

Police and fire officials suspected arson. The fire was started with an incendiary device, the hose sabotaged. Nobody was ever caught. The town soon rebuilt in brick.

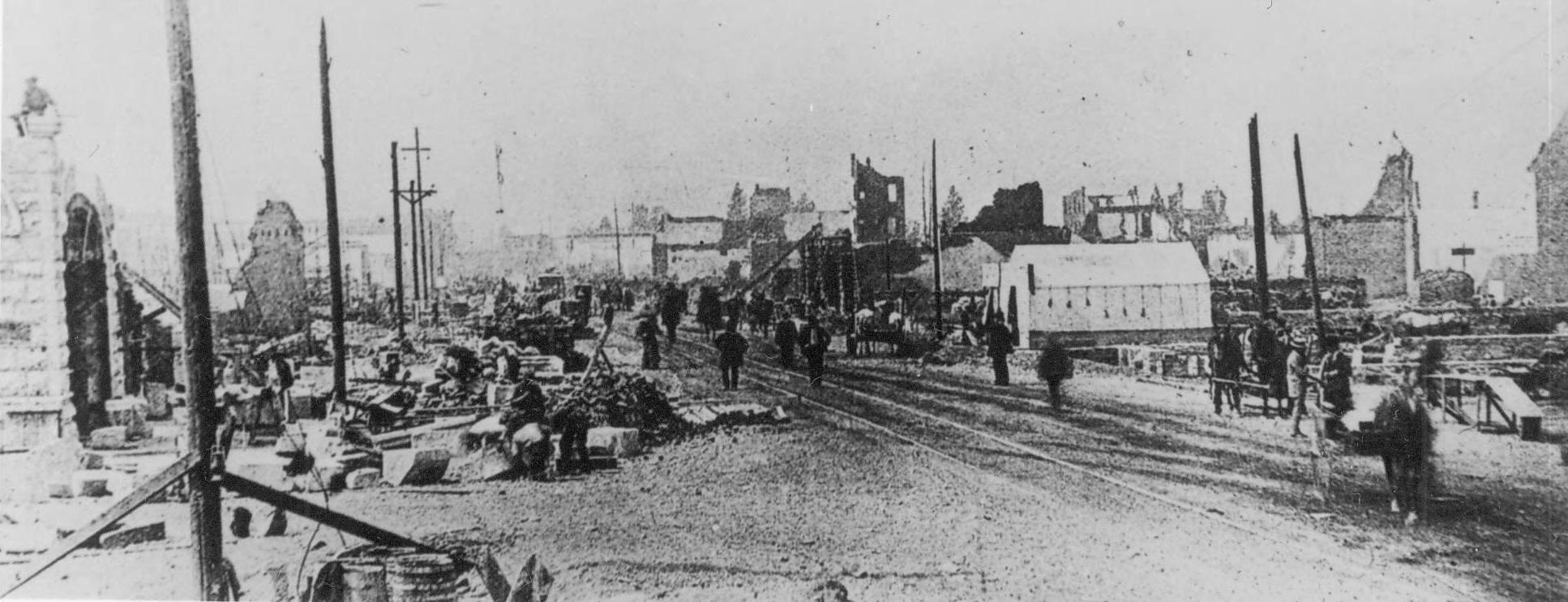

Seattle, after its own great fire. UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

Seattle was next. June 6, glue caught fire at a woodworking shop.The fire was helped on its way by an exploding liquor store and two saloons. Once fueled by alcohol, the flames were unstoppable.

By the time it ended the next morning, 29 square blocks were destroyed. The fire consumed 10 brick buildings, the whole business district, and the city’s railroad terminals.

Seattle had limited water with which to fight the fire. Hydrants were far apart; pipes were made of wood and burned with the rest of the city. The fire chief was out of town that day: attending a fire-fighting convention in San Francisco.

In the end, damage may have been as high as $20 million – more than 500 million in today’s dollars. But businesses didn’t flee the city. Most rebuilt where they were – but in brick, as wooden buildings were banned.

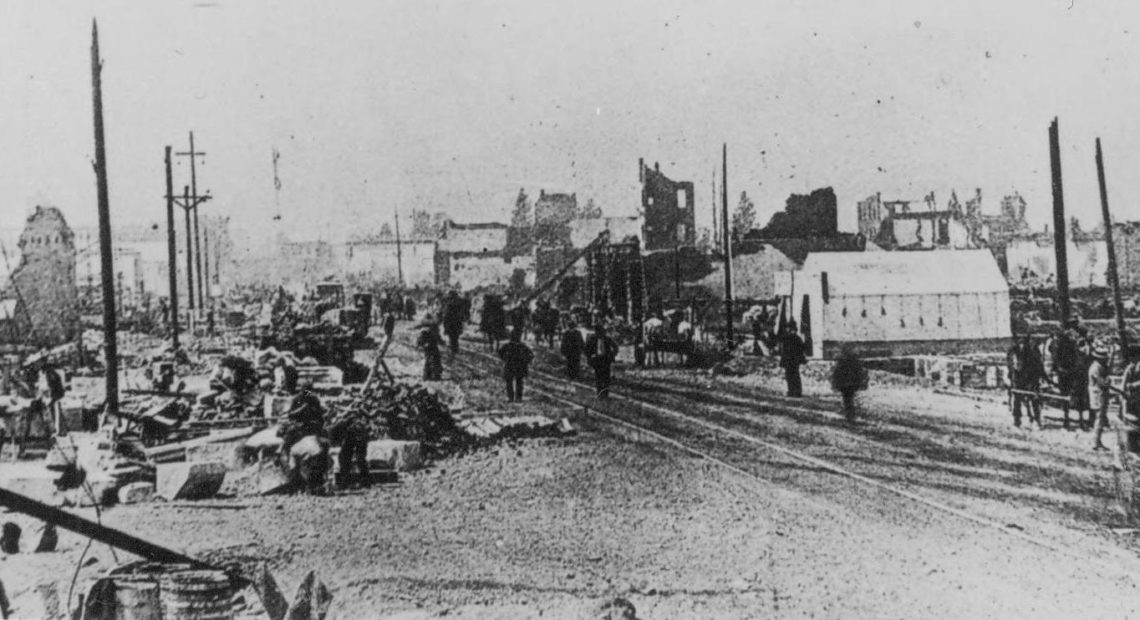

Little was left after Ellensburg’s fire. KITTITAS COUNTY HISTORICAL MUSEUM

A month later, Ellensburg celebrated Independence Day without fireworks in response to Seattle’s blaze. The city burned anyway. Around 10 that night, a store caught fire. Powerful winds fueled the blaze. Citizens at a dance tried to put it out but the fire burned through downtown Ellensburg with such intensity that it was seen from North Yakima.

Much of the city was destroyed. Not everyone agreed on the cause.

J.S. Anthony, the store owner, insisted it wasn’t an accident that lit his store ablaze. Others argued it was oil-soaked rags left in the store, or even an illegal still used to make moonshine.

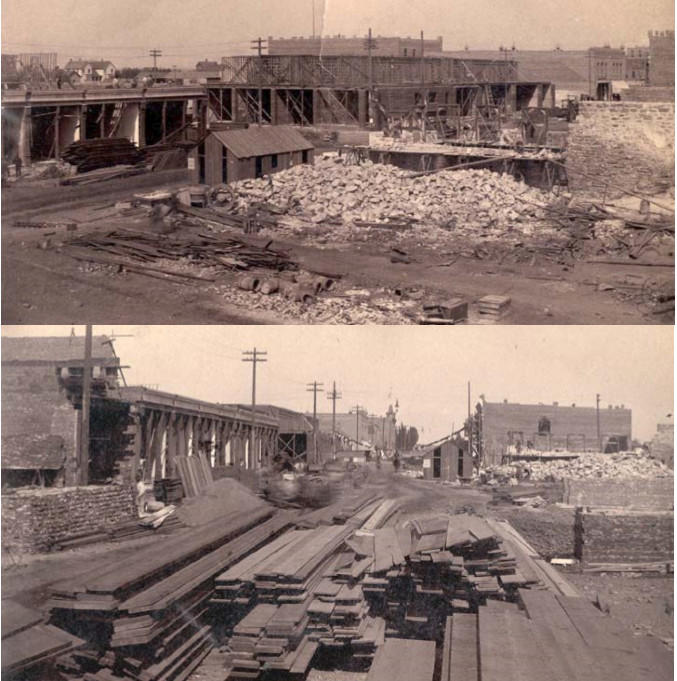

People around the country donated goods and material to Ellensburg’s recovery efforts. KITTITAS COUNTY HISTORICAL MUSEUM

Rumors swirled. Some blamed Chinese immigrants, some a traveling circus. Or was it illegal fireworks, set off despite the ban? A few believed it was ignited by citizens of Olympia or North Yakima, Ellensburg’s rivals for the capitol seat, which had still not been decided. But both cities, along with others nationwide, rallied to Ellensburg’s aid.

Fueling the mystery, prominent citizens reported strange notes at their homes the next day. On bright red paper, they read: “You have no pity — we have no mercy.” The question of who left them was never answered.

The next month was hotter and drier. Washington was on edge, still recovering from its two great fires. August 4, exactly one month after Ellensburg ignited, a restaurant in Spokane (then named Spokane Falls) lit up. With shifting wind and no water pressure in hydrants, firefighters couldn’t hold back the flames.

The mayor ordered the demolition of dozens of buildings with explosives. He was hoping to slow the fire’s spread. It didn’t work. The explosions drove the city’s hysteria as the wind changed direction and the fire burned toward the south.

The fire drew national attention, and supplies poured in. So many, in fact, that the city couldn’t use them all. City officials began to take supplies home, and two councilmen and a police officer were later indicted. There was no trial, and the men keep their positions. The following year, several city council members were suspended or expelled for bribery, related to the incident.

The city used large insurance payouts and tax money to improve the water and pumping facilities that had failed during the fire. And, like Cheney, Seattle and Ellensburg, they rebuilt in brick.

This post was originally published April 20, 2017.

Copyright 2017 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

How does climate affect your life? Tri-Cities survey open now

Cities, towns and counties are starting to plan for a future with climate change. Now, the Tri-Cities area is asking people about regional hazards and historical trends. (Credit: Simon Foot

Con manifestación en Tacoma, Unión de Campesinos llama a boicot contra Windmill Mushrooms

Personas de diferentes lugares del estado de Washington viajó a Tacoma para manifestarse en apoyo a los trabajadores agrícolas frente a una tienda Safeway el lunes por la tarde.

NASA astronaut José Hernández inspires students during visit to Tri-Cities

Surrounded by students seeking autographs and photos, astronaut José Hernández finished one of his conferences at Pasco High School.