Three Things You Should Know About Chinook Salmon, Key To Orca Survival

The Puget Sound region is home to three “resident” populations of orcas, so called because they spend “about half of the year foraging in inland waters,” according to a report from the University of Washington. These whales are the focus of an executive order signed by Governor Jay Inslee on March 14. It directs seven state agencies to take actions to protect orcas.

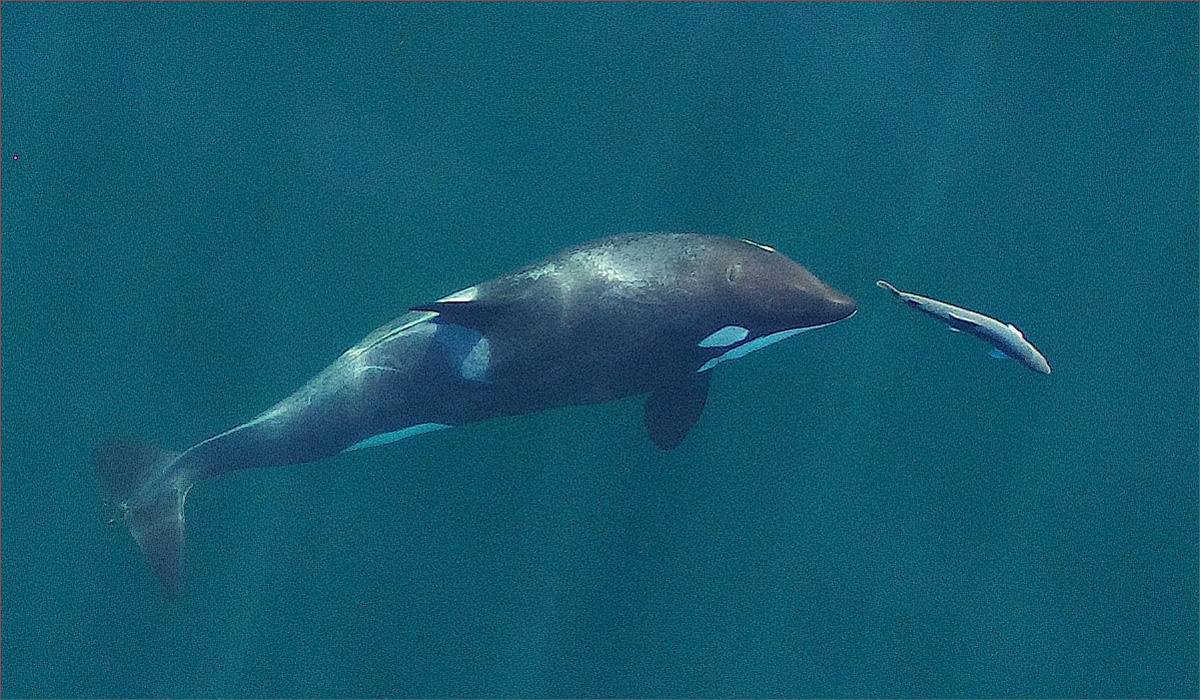

The whales survive largely on a single food source: Chinook salmon migrating from Northwest rivers. As Chinook populations have declined, orcas have struggled to find enough to eat.

Whales aren’t the only Chinook snackers. Bears, birds of prey, even seals, not to mention humans. Those animals consume other salmon species in addition to the Chinook, but orcas rely almost entirely on this single fish.

Here are three things to know about Chinook salmon and the role they play in the Northwest ecosystem.

There are six Chinook populations in the Northwest. All are threatened.

Chinook populations are divided into nine “evolutionarily significant units” (ESUs) by the federal government. Six are found in Northwest waters, and three more in California. One of these, the Upper Columbia River Spring-run Chinook, is endangered. The others are all listed as threatened. They face overfishing, habitat loss, and dangers from hydroelectric dams and development.

This year, Washington officials expect particularly low numbers of salmon returning to Northwest rivers, possibly due to changing ocean conditions.

Chinook have lost genetic diversity, and European settlement may be the cause.

As populations become divided from each other by habitat loss, that means fewer possible genetic combinations. This is a serious problem, making these species vulnerable to disease and environmental changes.

Northwest scientists, examining ancient salmon bones, found a decline in genetic diversity in Chinook salmon, which correlates to the arrival of European settlers. They also saw greater genetic diversity loss with populations in the upper Columbia River than in the Snake.

When Chinook salmon spawn, they can reshape the landscape.

No, really. Salmon sex has changed the shape of Washington’s rivers and mountains. When salmon spawn, the females dig holes in the river bed. That sends sediment downstream. It may not be a lot per fish, but when you have thousands and thousands every year, it adds up. A WSU researcher, Alex Fremier, called it “dump trucks of sediment.” This changes how rivers flow, and erosion rates of the land. Spread that out over five million years and some watersheds may be as much as 30 percent lower than similar bodies without salmon, according to Fremier’s study. If you want all the dirty details of this mountain-moving salmon sex, you can find that study published in the journal “Geomorphology.”

Copyright 2018 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Canadian leaders hope trade negotiations won’t derail Columbia River Treaty

A view of the Columbia River in British Columbia. The Columbia River Treaty is on “pause” while the Trump administration considers its policy options. However, recent comments by President Donald

Snake River water, recreation studies look at the river’s future

People listen to an introductory presentation on the water supply study findings at an open house-style meeting in Pasco. After they listened to the presentation, they could look at posters

Fish hatchery transferred to Yakama Nation, upgrades underway

Yakama Nation tribal members fish in the Klickitat River for fall chinook salmon. The Yakama Nation recently gained ownership of a fish hatchery on the river. (Credit: USFWS – Pacific