In Rural Washington, Pediatricians A Scarce Commodity As Medicaid Payments Aren’t Enough

Listen

“Everyone asks me what I’m going to do and I don’t know,” she said. “I won’t know ‘til I turn out the lights and lock the doors. I guess this is the last episode of ‘Cheers’.”

In January, the clinic closed its doors to all patients due to financial trouble. The cost of healthcare has been rising in recent years, including the costs of operating a clinic, but the strain has been magnified for pediatric providers who serve large low-income populations.

About 80 percent of the patients this clinic once served were insured through Apple Health, the state’s Medicaid program. In Aberdeen, there’s a large concentration of low-income families who rely on Apple Health to pay for care.

But Apple Health pays only a portion of the actual cost of an office visit. That reimbursement rate is set by the state.

For providers with large portions of their patients on Apple Health, the low reimbursement rate makes it difficult to stay in business, according to Jill Hutton.

“A lot of physicians won’t accept them because they can’t get paid and they can’t get paid enough to take care of them,” Jill Hutton said. “In this country, I think that’s just a shame.”

In 2013, the federal government increased Medicaid payments for primary care providers, and the financial pressure was lifted. Some states kept those higher rates, but not Washington state– they only lasted a year. In 2014, the payment rate dropped back down again.

“To put it in numbers, we would get paid $78 for a visit,” Jill Hutton said. “Now we’re getting paid $56. That’s a big cut.”

This year, legislators finally approved an increase in rates. But it’s unclear if it will be enough to help pediatric clinics that are in danger of shutting down.

Dreams Of Top-Notch Care

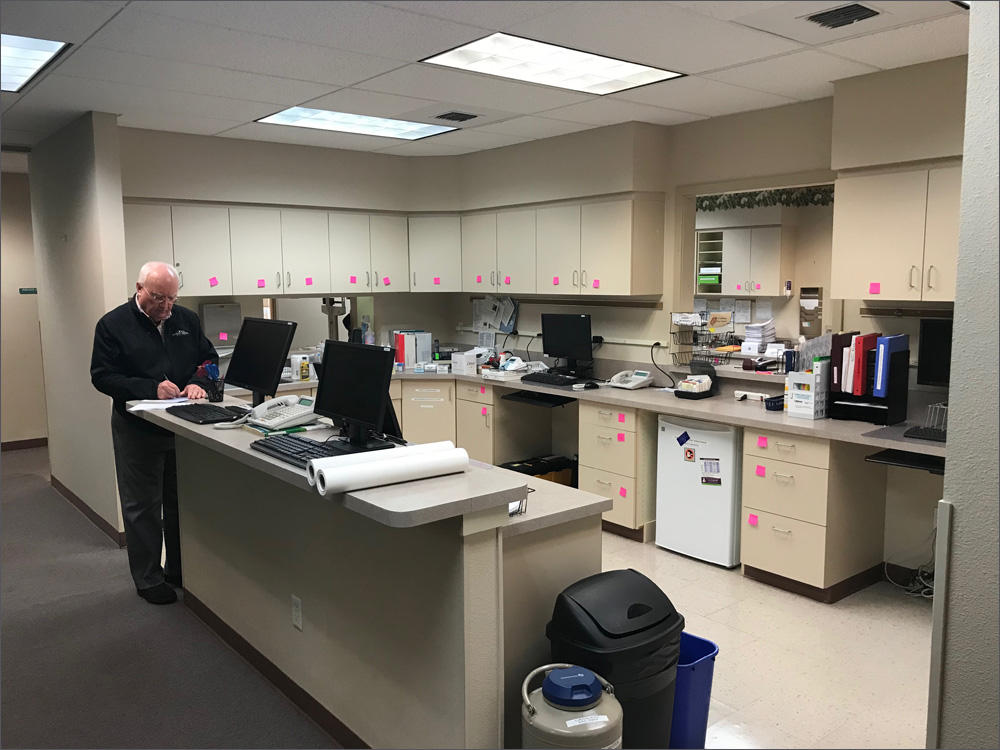

Stacks of unhung paintings sit on the floor of empty treatment rooms and offices. Cupboards are marked with pink post-it notes to signal that they’ve been emptied out. In the safari-themed waiting area, toys gather dust and a rectangular imprint on the carpet is all that’s left of a 100- gallon fish tank children used to peer into.

Dr. Steve Hutton, Jill’s husband and the owner of the clinic, was the head physician here. But now that the clinic is closed, he is practicing medicine at the Summit Pacific Medical Center in Elma, about 21 miles east of Aberdeen.

“It’s an easy transition in a sense,” Dr. Hutton said. “I’m still doing my same job that I do every day, it’s just in a different location and a different computer.”

Back when he was designing his office building, Dr. Hutton wanted to create a top-notch pediatric practice that rivaled anything you could have in the big city.

“And I wanted to outfit it the same way and provide really top-notch care for the children of Grays Harbor,” Dr. Hutton said.

He bought top-of-the-line medical equipment and he hired experienced nurses, doctors and other staff. The clinic is a big space with 10 exam rooms. The pediatricians Dr. Hutton employed treated children from all over Grays Harbor County.

Now, there aren’t any children running around the waiting area, no nurses filling out paperwork, and no doctors. The pediatricians that used to work here had to look for work elsewhere.

According to Sarah Rafton, the executive director of the Washington Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the low reimbursement rates for pediatricians have affected clinics all over, especially in rural parts of the state.

Without the support of large healthcare systems like Seattle Children’s Hospital or Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital, rural pediatric clinics must limit their intake of Medicaid patients. That means some people are turned away, and others have to wait months to schedule appointments or drive long distances to receive care.

“The problem with that is that you’re often asking low-income families to miss out on time for work and school,” Rafton said. “In the first few months of life, you have to go all the time for check-ups and vaccines. That travel burden becomes a real concern.”

Rafton said this can result in a domino effect where pressure is added to clinics and healthcare systems in urban areas as well.

Doctor’s Appointment Over The County Line

When Brenna Keller received a letter notifying her that the clinic in Aberdeen was closing, she made 30 phone calls trying to find a new pediatrician for her two children, who are 3 and 4 years old. But she kept getting turned away because providers did not accept insurance from Apple Health.

“I was upset, I was crying because I was just upset trying to find somebody who could care for my children,” Keller said. “It was really stressful.”

She finally found a new pediatric practice, but it’s over the county line in Centralia, more than 50 miles east of her home.

“I never thought that we would run into this issue,” Keller said. “I thought everybody would accept state insurance. That’s what the majority of the people around here are on.”

The Huttons said they would never limit their patients to just those with private insurance or those who pay cash. They don’t believe in doing that, and it also wouldn’t make financial sense.

“You can’t change your payer profile by closing out your Medicaid clients and saying, ‘I’ll take only insurance clients,’” he said. “There isn’t any here. There’s no jobs.”

More Money On The Way

This year, lawmakers in Olympia approved a supplemental budget that included almost $14 million to raise the reimbursement rate for pediatricians. It will go from 58 percent of the Medicare reimbursement rate to 75 percent.

According to Sarah Rafton of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the money will definitely help.

“It will provide meaningful support for clinics shouldering the financial burden of caring for large numbers of children on Apple Health,” she said.

But it’s an open question how much that money will help clinics that are struggling.

Even with the new funding, it’s unlikely clinics that have shut down will open again, Rafton said.

For Dr. Hutton, the money comes too late. He’s already moved on. He’s glad he’ll be able to continue his work at the Summit Pacific Medical Center, but he’s still disappointed.

When he set out to start the practice in Aberdeen 16 years ago, he wanted to leave a legacy for the children of Grays Harbor County.

“I wish the finances had worked out better,” Dr. Hutton said. “I wish I could have done it like I was ‘til it came to an end but there’s some things in the world you can’t control.”

Copyright 2018 Northwest News Network

Related Stories:

Nurses at St. Joseph in Tacoma seek staffing, safety changes

After their contract ended on Halloween, nurses at Tacoma’s St. Joseph Medical Center spent a rainy Friday morning picketing outside the hospital.

The nurses’ union, Washington State Nurses Association or WSNA, has been negotiating with hospital management since August. But Pamela Chandran, director of legal affairs for the union, said there are sticking points.

Whitman County reports two cases of pertussis

Pertussis, or whooping cough, is circulating across Washington, with two cases reported in the student population at Washington State University on Tuesday.

Health care professionals say Idaho law leaves gaps in care for minors

If you’re under 18 in Idaho, a new state law says you can no longer get any kind of health care outside of emergency treatment without consent from a parent. NWPB’s Rachel Sun reports.