How Will ‘The Big One’ Earthquake Affect Portland And SW Washington? New Study Estimates

No one can say when exactly the next Cascadia megaquake will strike other than there’s a fair chance it’ll happen in our lifetimes. A new study of likely earthquake impacts in the Greater Portland region finds the exact timing and season make a big difference when it comes to casualties and damage.

Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries modeled the impacts of a magnitude 9.0 offshore quake and a magnitude 6.8 rupture of the Portland Hills fault. There’s good news and bad news when applying the latest science.

The total damage is worse than previously estimated. But still, more than 99 percent of the population in the Portland metro area should survive. Lead study author John Bauer said the time of day the catastrophe strikes changes the death and injury toll by thousands.

“The best case would be say, summertime,” he said. “Folks are outside enjoying themselves. They’re not in buildings. Worst case is we’re in schools and our workplaces and it has been quite wet.”

In the rainy season there would be more landslides and building collapses. If the quake happens at night, more people survive because they’re sleeping in wooden homes that flex during the shaking.

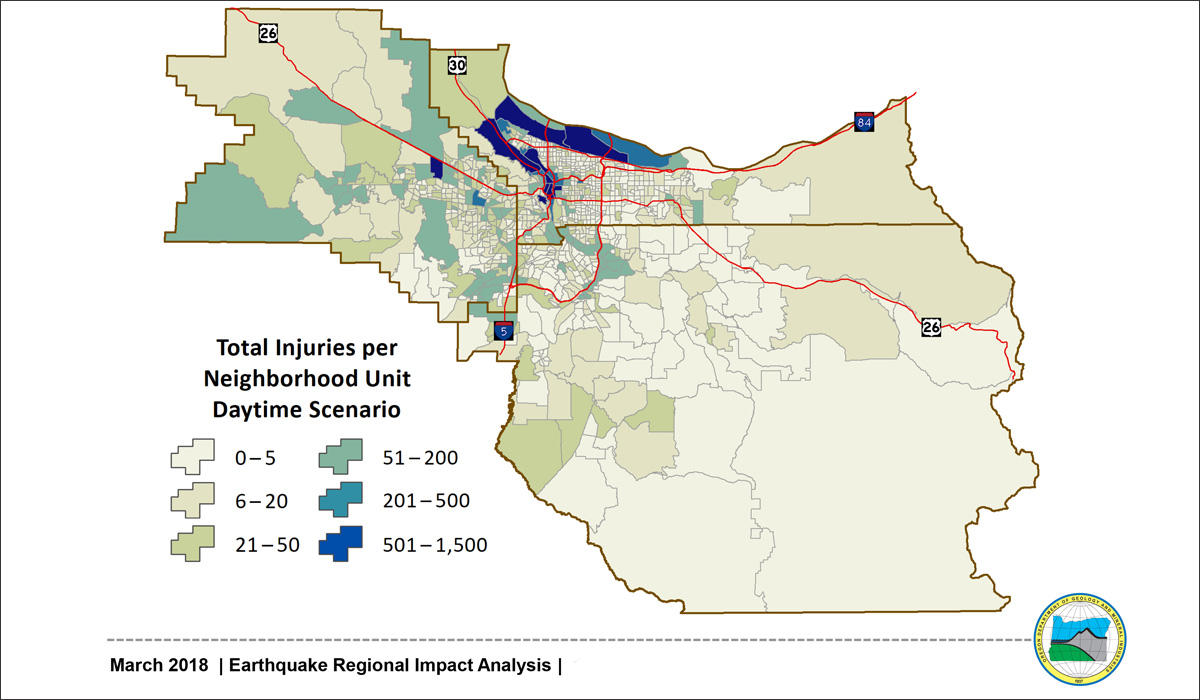

The estimated number of injured people in the Greater Portland area after a Cascadia subduction zone earthquake ranges from about 4,000 if the M9.0 temblor strikes at night during the dry season to around 27,000 if it happens on a workday afternoon in the wet season.

Bauer expects most of the injuries would not require hospitalization in any case. The total population of the study area is 1.64 million.

This map shows the estimated number of injuries from a magnitude 9.0 earthquake in the Greater Portland area. CREDIT: DOGAMI

“Hopefully people will see this is not doomsday, but it is something we can and should prepare for,” said DOGAMI Communications Director Ali Ryan Hansen in an interview. “This is an extremely survivable disaster… but what about the ‘after’? What about the next day? Where are we going to live? What are we going to drink?”

The study estimates between 17,000 and 85,000 people would be displaced long-term because their homes would be red-tagged—in other words, deemed unsafe to live in.

The study predicts 1,609 buildings would collapse if The Big One happens when soils in the metro area are saturated. Fewer than half as many buildings would collapse—an estimated 668—if the Cascadia megaquake strikes during the summer because the risk of soil liquefaction would be minimized.

“Accurate estimates of injuries and people in need of shelter helps us plan to care for injured people, and to meet the needs of people whose houses or apartments won’t be safe to live in,” said Jay Raskin, chairperson of the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Commission, in a news release.

A five-county consortium of local governments called the Regional Disaster Preparedness Organization commissioned this study. Published online Thursday, it covers Multnomah, Washington and Clackamas counties—Oregon’s three most populous counties. The rest of RDPO’s territory—Columbia County, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington—will be folded into a follow-up report due in about one year.

The study combined layers of updated data on population, building construction types and ages, refined earthquake science, the underlying geology down to the census block and the latest modeling techniques.

RDPO Manager Denise Barrett said the level of detail provided in this study can be used in practical ways right away.

She said the estimates of disaster debris volume and geography will inform planning currently underway for where to site temporary debris collection and storage depots. Separate planning of emergency transportation routes to move disaster relief into the area and evacuate the displaced and injured may need amendment to account for roads now judged likely to be severed.

In advance of an earthquake response exercise in 2016, the Federal Emergency Management Agency estimated the impacts of a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and tsunami across the whole Cascadia region from northern California to British Columbia. The worst case injury totals in the more recent Greater Portland study nearly equal the numbers FEMA calculated for all of Oregon and Washington a couple of years before.

FEMA told exercise participants the earthquake could injure over 20,000 people across the region. Minutes later, the tsunami would injure “several thousand more in the coastal region.” When combined with further injuries from aftershocks, hazardous material releases and contaminated water supplies, FEMA’s scenario projected as many as 30,000 injured survivors could seek medical treatment regionwide.

A team at the University of Washington called the M9 Project is now doing its own modeling of the impact of a Cascadia earthquake on Seattle and the wider region, which could provide more detail and nuance. For Seattle, the simulations shows significant variations in the intensity of shaking and results depending on where on the Cascadia fault the big quake originates.

Related Stories:

Seismic Research Ship Goes Boom-Boom To Seek Answers At Origin Of The Next Big One

Earthquake researchers are eager to dig into a trove of new data about the offshore Cascadia fault zone. When Cascadia ruptures, it can trigger a megaquake known as “the Big One.” The valuable new imaging of the geology off the Oregon, Washington and British Columbia coasts comes from a specialized research vessel.

West Coast Now Covered By Earthquake Early Warning System With Addition Of Washington

Residents living on the West Coast don’t know when the next earthquake will hit. But a new expansion of the U.S. earthquake early warning system gives 50 million people in California, Oregon — and now Washington — seconds to quickly get to safety whenever the next one hits.

When ‘The Big One’ Hits The Northwest, What Could You Do With A Few Seconds Warning?

Smartphone users who opted in to a test of the West Coast earthquake early warning system got an early taste on Thursday of what is to come. Mobile phones from Seattle to Olympia blared with an alarm for imaginary incoming shaking. The earthquake warning system — already operational in California — will launch for the general public in Oregon on March 11 and statewide in Washington in May.