Now On Immigration’s Front Lines, Sheriffs Are Choosing To Back Or Snub ICE

BY JOHN BURNETT & MARISA LAGOS

Anytime someone is booked into a county jail for a crime in the U.S., his or her fingerprints are automatically sent to federal authorities. If the suspect happens to be an undocumented immigrant, what happens next could depend on where the jail is located.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement often asks jails to hold undocumented people, so federal agents can pick them up and put them into deportation proceedings.

Most counties comply with those detainer requests. And the Trump administration has been building on these partnerships with local law enforcement in friendlier jurisdictions.

But across America, so-called sanctuary cities and states have taken a stand against the administration’s immigration crackdown. They say it’s not their job to enforce immigration law, and they don’t comply with requests.

The administration has responded by ratcheting up the pressure. It has threatened to take away federal funding from the local jurisdictions. And on Thursday, President Trump threatened to pull federal immigration authorities out of California.

“If we said, ‘Hey let California alone, let them figure it for themselves,’ in two months, they’d be begging for us to come back,” Trump said. “They would be begging. And you know what, I’m thinking about doing it.”

California: ‘You don’t have to worry about immigration’

California and several cities in the state have sanctuary laws. In San Francisco, that means when ICE asks local jailers to turn over an undocumented immigrant, they can comply only if the inmate has a history of violent crime.

Attorney Nick Gregoratos with the sheriff’s office recently set up shop at in a small room at the San Francisco County jail. He introduces himself when the first inmate walks through the door.

“We have to give you some information regarding immigration ’cause immigration has asked us about you so I want to give you that information,” he said.

The inmate tensed up when immigration is mentioned. Gregoratos explained that Immigration and Customs Enforcement wants the sheriff to detain the inmate until federal agents can take him into custody or to let ICE know when they plan to release him.

But Gregoratos said the sheriff won’t cooperate with those requests.

“So while you’re here in San Francisco you don’t have to worry about immigration coming to the jail and trying to pick you up,” he said.

In fact, Gregoratos was there to help this inmate. He gave the man a packet of information. It includes legal resources for undocumented immigrants.

“Esta bien, muchas gracias,” the inmate said, thanking Gregoratos.

Because of jail policy, we can’t use his name without his permission. And he said he doesn’t want to be identified because he’s scared.

He said he was deported back to Mexico a decade ago but returned. He was recently arrested for assault and battery, which sounds violent, but doesn’t fall under San Francisco’s strict definition of a violent crime.

The inmate was waiting to be arraigned. He said through an interpreter that he would call one of the immigration attorneys recommended by Gregoratos. “Yes, I am going to talk to them will see what we can figure out,” the inmate said.

California has stepped up protections for undocumented immigrants. As of Jan. 1, San Francisco Sheriff Vicki Hennessy also is required to tell inmates when ICE is looking for them. She says they have a right to know.

“Anytime you’re in jail for anything, and there’s any kind of document that comes up that has something to do with you that is about you and could affect you, you generally get a copy of that,” she said.

Hennessy says she would honor any federal court warrant for an inmate in her jail. But she says those ICE detainer requests are just a form filled out by an ICE agent — not a legally binding document.

This is all part of a larger battle playing out between the Department of Justice and sanctuary cities and states.

Local officials across the nation worry if they work too closely with ICE, immigrants won’t feel safe cooperating with police. Federal officials say the opposite — that these sanctuary policies make the public less safe.

In its latest move, the Department of Justice has threatened to subpoena local officials if they don’t turn over documents by Friday to show whether they are sharing information with ICE.

Meanwhile, ICE agents continue to raid immigrant communities. They took more than 100 people into custody during recent operations across Los Angeles.

In a statement to NPR, ICE said if its agents can’t get into jails, they will be forced to carry out more raids.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra says local law enforcement shouldn’t have to spend limited resources helping enforce federal laws against people who pose no danger to the public.

“Immigration may have the right to chase those folks because they may not have documents but it certainly doesn’t necessarily make our communities safer,” he said.

Texas: ‘We Don’t Want ‘Em Here’

The coastal bend of Texas is a world away from San Francisco. Here you find the biggest cluster of counties in the nation that have partnered with ICE. Twelve sheriffs have agreed to help the federal government enforce immigration laws by turning over undocumented immigrants they happen to arrest.

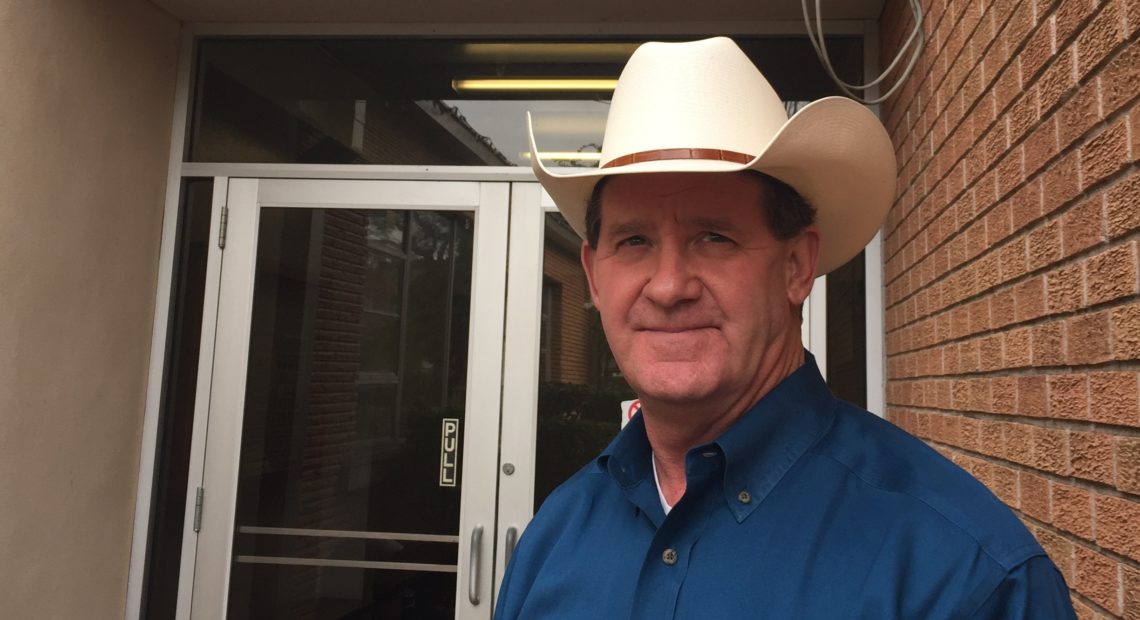

The first was Jackson County, where Andy Louderback is sheriff.

“If they’re driving around this county intoxicated; if they’re stealing from people,” he said, “If they’re committing crimes … we want them removed from the country. We don’t want ’em here.”

The popular sheriff is in his fourth term. His rural county is located on the Gulf Coast, about midway between Houston and Corpus Christi.

About three-quarters of the nation’s 3,000 counties cooperate with ICE, according to a recent survey by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. Jackson County is one of a few dozen law enforcement agencies in the country that have gone even farther.

They send jailers to a month-long ICE academy where they learn how to identify prisoners who are in the country illegally. Then, ICE gives the county a dedicated computer to send a detainee’s personal information directly to the agency.

Tara Timberlake, a supervising jailer in Jackson County, explains.

“You just talk to them just like ask ’em their name,” she said, “where they’re from, and if they’ve come over to the United States legally or illegally.”

Louderback says he even set aside a room in the jail. He says they refer to it as the “ICE booking station.”

Louderback says he and the other coastal sheriffs in Texas signed up for the ICE program — it’s called 287g — to crack down on immigrant crime. The U.S. highway their counties straddle is a pipeline for smuggling drugs and humans from Mexico.

He figures at any one time, he’s holding five unauthorized immigrants in his jail until they can be picked up by ICE. Yet, most are not accused of being cartel operatives. They’re young men like Pablo Garcia.

Garcia is a 21-year-old undocumented house painter from Mexico. He’s dressed in black-and-white jail stripes, with a sallow jailhouse complexion.

“I was trying to stay in the shadows, just working and going home,” he says in Spanish. The cops came to his house in the county seat of Edna looking for someone else, but he says they ended up arresting him for possessing a small bag of cocaine.

Because Garcia was holding less than a gram of cocaine, he will likely get probation. But he’s almost certain to be deported.

ICE statistics show that most of the immigrants it takes into custody from local jails are there for crimes like driving while intoxicated, assault, and drug possession. Not the grave crimes the Trump administration highlights, like homicide and rape.

Asked if he considers Garcia a dangerous criminal who would pose a threat to public safety if released, Louderback says he “can’t really answer that.”

“You know, he was picked up for possession of a controlled substance. I mean, there’s plenty of evidence about the violence associated with the drug trade. Whether he particularly is a potential threat, we can’t really answer that, can we?”

For Andy Louderback, the severity of the offense is irrelevant.

“If you’re here illegally and you’re not a citizen, that’s crime one. And now you’re here in this community, and you commit another crime here.”

Sheriff Louderback stresses that he’s not interested in rounding up all undocumented workers in Jackson County — he estimates there are about a thousand. He says he’s only interested in the ones who end up in his jail.