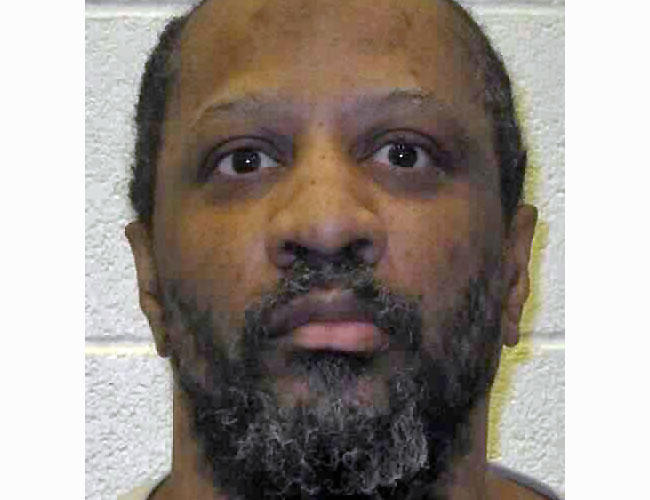

Washington Death Row Inmate Loses Court Challenge Over Intellectual Disabilities

Listen

On January 25, 1997, Cecil Emile Davis, a “violent offender” on state supervision, broke into the Tacoma home of 65-year-old Yoshiko Couch.

Once inside he raped and beat her and then suffocated her by holding a rag soaked in cleaning solvents over her mouth.

Davis was later convicted of aggravated first degree murder and sentenced to death.

On Thursday, the Washington Supreme Court rejected Davis’ claim that Washington’s death penalty system is unconstitutional because it doesn’t protect death row inmates with intellectual disabilities—sometimes referred to in the courts as “mental retardation”—from execution.

“We find his arguments unpersuasive and dismiss the petition,” Justice Steven Gonzalez wrote in a majority opinion signed by six of the nine justices.

Washington law and the U.S. Constitution prohibit executing someone who’s intellectually disabled. In Washington, that determination is made by the trial judge after a guilty verdict is rendered.

At trial, Davis argued that the jury, not the judge, should have to find beyond a reasonable doubt that he didn’t have an intellectual disability. The trial judge rejected that motion.

At sentencing, Davis’ lawyer made the case for mercy based on a variety of issues including “low intelligence,” but did not make the case that Davis had an intellectual disability that constitutionally excluded him from the death penalty.

Nor did Davis make that case on appeal. In fact, his attorney wrote, “Davis does not claim he is intellectually disabled or that he was intellectually disabled at the time of the crime.”

However, in 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court found that Florida’s death penalty system failed to use the appropriate criteria for determining intellectual disability, thus creating the risk that inmates with intellectual disabilities would be executed. Based on that ruling Davis argued to the Washington Supreme Court that Washington law, which is similar to Florida’s, “creates an unacceptable barrier to proof of intellectual disability.”

Under Washington law, a defendant must have an IQ of 70 or below before the court will consider whether there’s an intellectual disability. A doctor in Davis’ case testified that he had an IQ score of 68, although other tests indicated he might have a higher score.

In their majority opinion, the justices allowed that Washington law may have similar flaws to Florida’s, but concluded that wasn’t a factor in Davis’ case.

“Essentially, Davis argues that he is entitled to resentencing since [the Florida case] makes clear that using a 70 IQ as an evidentiary cutoff is unconstitutional,” the majority wrote. While that test might not be constitutional, the Washington justices concluded that Davis wasn’t harmed by it because his intellectual capacity was, in fact, considered by the court.

“Davis has not established that our death penalty statute, or his sentence, was unconstitutional,” concluded the majority.

The justices also rejected Davis’ assertion that a jury, not a judge, should determine intellectual disability.

However, in a concurring opinion, Justice Sheryl Gordon McCloud argued that the Supreme Court should give more attention to the question of how an intellectual disability is determined.

“This is a complex constitutional issue … we have the obligation to explore,” McCloud wrote in an opinion also signed by Justice Mary Fairhurst.

In a lone dissent, Justice Barbara Madsen took the opposite view. She argued that Davis’ death sentence should be reversed on the grounds that the judge, not the jury, decided whether he was intellectually disabled. Madsen said Washington law requiring the court to make that determination violated Davis’ Sixth Amendment rights, based on the 2014 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the Florida death penalty case.

Madsen also said that Davis’ IQ score of 68 cannot be disregarded. “That evidence alone creates a fact question as to whether Davis suffered from an intellectual disability,” Madsen wrote.

In a statement, Pierce County Prosecutor Mark Lindquist said, “Davis’ crimes shocked the conscience of our community. We hope this brings closure for the community, especially the family and friends of Yoshiko Couch.”

Davis, who’s African American, is one of seven men on death row in Washington. However, the state is not carrying out executions because of a moratorium imposed by Gov. Jay Inslee in 2014.

The Washington Supreme Court has another case pending that could test the constitutionality of the death penalty. Lawyers for death row inmate Allen Eugene Gregory, who is also African American, are challenging the state’s capital punishment statute on the grounds that it is “infected with arbitrariness and racial bias.”

Copyright 2017 NWNews.

Related Stories:

Washington, Idaho rank high for public health emergency preparedness

Both states saw steady or increased funding for public health, but Idaho still among lowest for vaccinations.

How does climate affect your life? Tri-Cities survey open now

Cities, towns and counties are starting to plan for a future with climate change. Now, the Tri-Cities area is asking people about regional hazards and historical trends. (Credit: Simon Foot

Con manifestación en Tacoma, Unión de Campesinos llama a boicot contra Windmill Mushrooms

Personas de diferentes lugares del estado de Washington viajó a Tacoma para manifestarse en apoyo a los trabajadores agrícolas frente a una tienda Safeway el lunes por la tarde.