How 11 Suicides Forced Change Inside Washington Prisons

Listen

In 2014 and 2015, Washington’s prison system experienced a spike in inmate suicides. During those two years 11 inmate deaths were ruled suicides, giving Washington one of the highest prison suicide rates in the country. Austin Jenkins has spent the past year investigating how this happened and how the prison system responded.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call for help now. The National Suicide Prevention Hotline is a free service answered by trained staff. The number is: 1-800-273-8255.

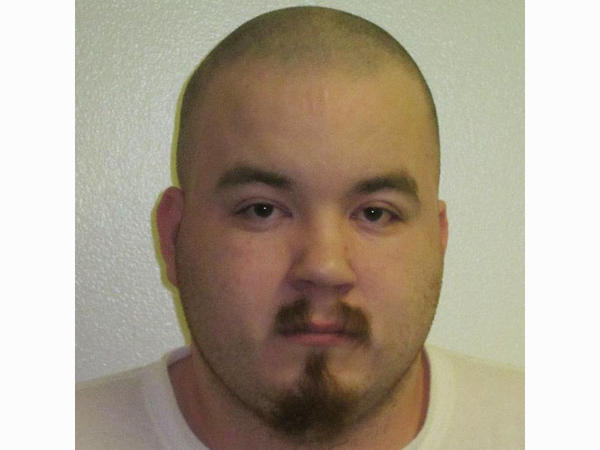

On the morning of October 16, 2014, Nicholas White was found hanging by a sheet from the vent in his two-man cell in the Washington Corrections Center.

White, inmate number 898972, had just arrived at the prison seven days earlier to serve a one year sentence for unlawful possession of a firearm. It was the 31-year-old’s second time behind bars.

That morning started out routinely at the prison near Shelton. Surveillance video shows shirtless inmates playing basketball in a gym. You can also hear the idle chatter of correctional officers in an office off the gym.

But then, at about 9:45 a.m., White’s cellmate stops by the office and tells a sergeant that White has been acting paranoid and talking about killing himself.

“I caught him this morning like where the vents are,” White’s cellmate is heard saying on the tape. “He’s trying to tie a sheet up there to see if it will f—— stay.”

The cellmate leaves and the sergeant goes to tell his lieutenant. He then checks on White.

About 15 minutes elapses from when the cellmate alerts staff to when the call for help goes out over the radio.

In the video you can hear the staff react: “Oh s—. You better go take care of that. Go, go, he’s hanging.”

Even as the emergency response begins, everything else goes on as normal. The basketball game continues. The inmates in the gym have no idea one of their own is hanging in a nearby cell.

At 10:21 a.m., a prison doctor declares White dead.

A hand-held video from that day shows the ambulance crew leaving. White’s body remains on the floor outside of his cell. A correctional officer walks up and places a white sheet over the body. Someone is heard saying, “It’s an unfortunate day.”

White was the fifth Washington prison inmate to die by suicide in 2014. In a normal year, two or three inmates might take their own lives. This spike in suicides set off alarm bells within the Department of Corrections. But not immediately.

“We started seeing an increase,” says Dr.Karie Rainer, who directs mental health services for the Washington Department of Corrections. “And I would say at around the fourth suicide, we started to become concerned. It was different than previous years.”

So they started to look for patterns and commonalities.

“While we were looking,” Rainer says, “we continued to have suicides that were completed, which just further raised our concerns.”

After Nicholas White, there was one more suicide in 2014. Then in 2015, five more inmates took their own lives.

If there was a pattern to these deaths, it wasn’t easily detectable. The victims were housed in different prisons, were different ages, had committed different crimes. Some were serving long sentences, others were about to get out. Some had known mental health issues, others weren’t on anyone’s radar.

So who were these men?

The first to die was Richard Billings, Jr., 38. He was found hanging in his cell at the Stafford Creek Corrections Center near Aberdeen just after 3 a.m. on January 13, 2014. Billings was serving a 12 year sentence for child molestation. He had a history of more than 20 suicide attempts throughout his life. Just prior to his death Billings was taken off suicide watch and moved to a single cell. His therapist later told investigators that Billings should not have been placed in a single cell given his heightened risk for suicide. Before he died, Billings wrote a 45-page manuscript describing his reasons for taking his own life. He also sent his parents his last will and testament.

The next was Tony Willoughby, 48. He hanged himself in his cell at the Airway Heights Corrections Center near Spokane on April 7, 2014. Willoughby was serving life without parole for murdering an 87-year-old woman and had been in prison for nearly three decades. He was not considered a risk for suicide. The night before, Willoughby had been seen “happy and joking” at dinner.

On May 29, 2014, also at Airway Heights, Morgan Bluehorse, 29, was discovered hanging by a sheet from the steel cage protecting the fire sprinkler head in his isolation cell. Bluehorse was serving 15 years for a string of burglaries and had a history of suicide attempts dating to his childhood. He had just arrived at Airway Heights the day before and was put in a solitary cell in the Special Management Unit after reporting that he had been threatened by other inmates.

On August 18, 2014, once again at Airway Heights, Chance Kidder, 19, hanged himself—also from the sprinkler head protection cage in his isolation cell. Kidder had been scheduled for release from prison the following day after serving time for auto theft. However, three days earlier Kidder had been placed in the Special Management Unit after getting in a fight with another inmate. As a result his was facing a delay in his release.

The next suicide was Nicholas White at the Washington Corrections Center, the inmate who was found shortly after his cellmate alerted staff. It turns out White had tried to get help. An investigation revealed that three days before his death he had asked to see a mental health counselor. The following day he submitted another request and said he wanted to get back on his medications “ASAP.” The day of his death, White had an appointment to see a counselor—but it appears no one let him know the appointment had been set up.

The sixth and final suicide of that year came the day before Thanksgiving also at the Washington Corrections Center. Keith Neal, 43, was found unresponsive in his top bunk after having cut his arm and bleeding out overnight. Neal was serving a 35 year sentence for multiple counts of child rape. The night before his death, Neal was honored by prison volunteers for his work as a teaching assistant in the Education Department at the Washington Corrections Center. But letters Neal left behind indicate he’d been storing adult pornography on a prison computer and believed he was about to be exposed.

After each of these suicides the Washington Department of Corrections conducted a Critical Incident Review—an investigation into what happened and whether policies were followed. Each review included timelines, interviews with staff and concluded with recommendations and lessons learned. Despite these reviews, the suicides didn’t stop.

The first three months of 2015 brought three more deaths. On January 5, Oscar Garcia-Pacheco, 34, was found hanging in his cell at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. On February 28, 23-year-old Nathen Bennett was discovered hanging in his cell in the Special Offender Unit for mentally ill inmates at the Monroe Correctional Complex. And on March 28, Jason Williams, 41, was found hanging from his orange jumpsuit in the Secured Housing Unit at the Larch Corrections Center near Vancouver .

To begin to understand prison suicide, it helps to understand suicide in general.

That’s something Sue Eastgard has been trying to do for more than 30 years. She’s a social worker and director of training at Forefront, a suicide prevention non-profit based at the University of Washington. Eastgard says everyone experiences emotional distress in their lives.

“We have bad days at work, we have upsets with our families, we’re frustrated with our adolescent children,” Eastgard says.

Usually people can cope with that distress—sometimes in healthy ways, sometimes in not so healthy ways.

“People use Chardonnay as a coping mechanism, they use marijuana, they call a friend, they take a bath,” Eastgard says.

But sometimes the emotional pain becomes too much.

“In suicide what you have is the pain outweighs the capacity or the ability to cope,” Eastgard says.

When this happens, intervention is necessary.

“So we teach around something called LEARN,” explains Eastgard. “The L stands for ‘look’ for warning signs, the E for ’empathize,’ the A for ‘ask,’ the R for ‘remove’ the means and the N for ‘next steps.'”

In prison, many of the means to suicide have already been removed. After all, inmates live in a restricted environment under close supervision. And there’s no access to firearms—the leading method of suicide in the U.S. But in other respects prison inmates may have a heightened risk for suicide. They’re locked up and deprived of social support systems. Many have an underlying mental health condition or have experienced childhood trauma. For some, the prospects of a long sentence may provoke hopelessness. For others a looming release date may bring on panic about having to survive on the outside.

The inmates who have died by suicide in Washington prisons can’t tell their own stories. But those who’ve tried and survived can.

Consider the case of Daniel Jay Perez, 30, who’s housed in the Special Offender Unit for mentally ill inmates at the Monroe Correctional Complex. Perez says his diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder and PTSD. He has a history of violence against others and also has a history of self-harm and suicide attempts.

Perez first went to prison in 2005 for vehicular homicide. He was 18. In prison he says he became paranoid and violent. Less than a year into his sentence Perez strangled his cellmate to death. Perez spent the next nearly three years in solitary confinement, locked down 23 hours a day. He was in a specialized mental health treatment program during this time, but even so Perez says the isolation took a toll.

“And that’s when my self-harm and suicidal ideation came back,” Perez says.

In 2009, Perez was moved out of isolation and back into a communal living setting within the Special Offender Unit at Monroe. But a few months later, he attempted to murder another fellow inmate. Once again he was put back in solitary confinement—this time for five more years. Two years into that stretch in isolation, he attempted suicide.

“I ripped up a sheet and made a ligature and wrapped it around my neck so tight that I lost consciousness,” Perez says.

Perez woke up in the hospital. He’d been saved by prison staff who performed CPR on him for about 30 minutes. Perez says he attempted suicide because of the isolation.

“The walls close in on you, they collapse on you,” in solitary confinement, Perez says. “You feel detached, you feel like there’s no stimulation. It’s an overwhelming feeling of anxiety, depression and paranoia.”

Today, Perez is out of isolation and once again living among his fellow inmates in the Special Offender Unit at Monroe.

There were no second or third chances for 19-year-old Chance Kidder.

He was taken off life support the day after he hanged himself in his isolation cell at the Airway Heights prison in August of 2014.

One of the witnesses to Chance’s suicide was a fellow inmate named Casmer Volk.

From his cell in the Special Management Unit, Volk could see into Chance’s cell.

“I could see that he was titled in a weird direction,” Volk said in a telephone interview from the prison last July. “I didn’t know what he was looking at. I didn’t know what he was doing.”

A few minutes later a correctional officer came through to check on the inmates. The officer pounded on Chance’s door.

“My heart just fell. I instantly knew exactly what was going on,” Volk said.

More officers arrived and they got Chance’s cell door open. He was hanging by a bedsheet from the steel protection cage covering the fire sprinkler.

“They ran in and cut him loose and he fell right into an officer’s arms totally limp,” Volk recalled.

Volk watched as the officers began CPR.

“You never expect to be seeing somebody killing themselves, right in front of you,” Volk said. “It was absolutely traumatic.”

A Department of Corrections investigation into Chance’s suicide praised the response from staff as “exemplary.” But it also found gaps leading up to his death. For instance, correctional officers were supposed to check on the inmates in solitary confinement every 30 minutes. But surveillance video showed it had been nearly an hour since an officer had last looked in on Chance. The report also noted that prison staff failed to follow up on information about Chance’s previous acts of self-harm. And then there was this finding: the sprinkler head cages in the isolation cells had been used in the last three suicide incidents at Airway Heights—yet the covers had not been removed.

For Chance’s foster mom Jackie Lunn that’s the unforgivable part.

“I don’t think that there should have been a way that he could hang himself in that cell,” Jackie says. “If they’d had it done before it should have been taken care of.”

Jackie and her husband Charlie got the news of Chance’s hanging in a late night phone call at their home in Kittitas, a central Washington farming community.

“That call,” says Jackie, “it was awful.”

It was a chaplain from the prison who called.

“He said [Chance] had committed suicide and I just lost it,” Jackie says.

Someone else was devastated by Chance’s suicide—his girlfriend Erica Littler. They had stayed together while he was in prison and kept in touch by prison email and phone calls. The pair had met in high school. He was a year older, a football player and wrestler. She was surprised when he asked her out.

“I was a really shy kid and he was the jock to me,” Erica says. “He was someone I never really thought I’d ever talk to or anything like that.”

Their first date was to see a period piece horror movie called “The Woman in Black.: They were the only two people in the theater. Soon they were an item. At school Erica says Chance was popular, charming; a standout on the football team. Outwardly, Chance came off as a happy guy. But the more Erica got to know him, she got to see another side.

“He struggled a lot mentally,” she says. “And he had moments where he just felt like he wasn’t good enough or he just didn’t deserve what he had.”

In the past Chance had sometimes cut himself.

“He would cut down his…ribcage,” Erica says.

Even so, Erica never thought of him as suicidal.

Chance’s childhood had been turbulent. He lived with his mom and two younger brothers on the Yakama Indian Reservation. When Chance was about five his mom was paralyzed when she dove into a local creek on a hot summer day. After that Chance and his siblings helped care for her.

Then just two years later Chance’s mom shot and killed her boyfriend in the kitchen of their home. According to a family member Chance hid the gun from the cops under his mattress. After that Child Protective Services got involved and placed Chance and his brothers with family members. Eventually they ended up in foster care. When Chance was 10 he was separated from his brothers, likely because of his behavior, and sent to live with the Lunns in Kittitas.

“He came with a sack of clothes, a grocery sack,” Jackie remembers, “and the clothes were either too little or too big.”

“And a dirty, nasty sleeping bag,” adds Charlie.

The first thing Jackie did was get him some new clothes. That created a new problem.

“I’d yell, ‘Chance, breakfast is ready, get down here,’ and he wouldn’t come, and he wouldn’t come, and he wouldn’t come,” Jackie says.

“And I’d go running upstairs and he’d be standing there looking at his closet. He couldn’t pick anything, he didn’t know what to pick. He never had the choices of picking clothes.”

Less than a year after Chance came to live with the Lunns, his mother died of a drug overdose. The death was ruled a suicide. After that, Chance remained in the foster care system living with the Lunns. Because they were older, he called them grandma and grandpa.

“It was easier for him to tell people, ‘I’m living with my grandma and grandpa,'” Jackie says.

The Lunns tried to give Chance his childhood back. They took him camping in eastern Washington and fishing off the coast. He rode steers in a rodeo. Family photos from that time show a sweet looking boy with a buzz cut and a farmer’s tan.

In high school Chance got the nickname Forrest Gump for his speed on the football field.

“He was the star of the show,” Charlie says. “He was very good.”

But off the field, Chance gave them trouble. Lying and stealing were his downfalls, Charlie says.

First it was petty theft—a neighbor’s bike, a teacher’s cell phone. He’d always return the item when caught. But the stealing didn’t stop.

“We kept telling him, ‘if you don’t change when you’re 18, this stuff’s not going to go away,'” Jackie says.

Then came the day in 2012 when Charlie Lunn watched police car after police car race past his barber shop on Main Street. Soon his phone was ringing. It was a nurse at the local hospital saying Chance had been hurt.

Chance, a high school senior, had been found bleeding at school from a gunshot wound to the shoulder. He told the police a black man had shot him, but that’s not what happened.

Chance and Erica had gotten in a fight after she had caught him messaging another girl. He said it was his cousin using his social media account. Erica says she believed him and thought they’d patched things up.

“He felt that I really hadn’t forgiven him and that he had done wrong,” Erica says.

Sometime that morning Chance left school. He walked a few blocks home, broke into Charlie’s gun case, armed himself with a .22 pistol, went out to the barn and shot himself. Erica says he later told her he was trying to kill himself and that he had moved the gun at the last moment. The bullet went into his shoulder.

“Crippled his right arm,” Charlie says. “Never did work right after that.”

After being hospitalized, Chance was sent to an inpatient psychiatric facility in Bellingham where he spent two weeks. Jackie says she talked to him twice a day.

“He said, ‘I don’t want to be here,'” Jackie says. “And I said, ‘you’ve got to be there. You’ve got to stay there and do their tests. You’ve got to do what they tell you to do.'”

Chance was then sent to live in a youth home in Lewiston, Idaho for four months so he could get further mental health treatment. When he was released, he returned to the Lunns’.

Less than a month later Chance turned 18 and aged out of foster care; he got a run-down apartment in the next town over. But the Lunns stayed involved in his life. Jackie made him complete his high school diploma. Soon though he was in trouble again. Chance stole an ATV from a farmer he worked for. While on probation for that, he and another man stole several cars from a used car lot. The judge sentenced Chance to 14 months in prison for theft of a vehicle. The Lunns were in the courtroom.

“He was ashamed of himself,” Jackie says. “He wouldn’t look at us.”

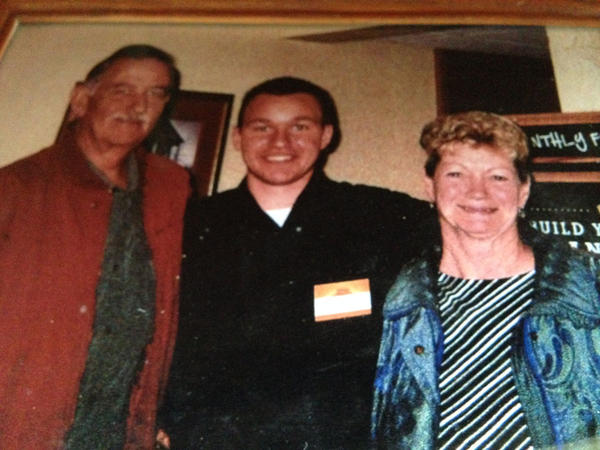

Once Chance got to prison he, like every new arrival, had to go through a physical and mental health screening. On a written form he disclosed his self-inflicted gunshot wound and the fact he’d gone to the Idaho youth home for treatment. But he denied being suicidal and there’s no evidence anyone followed up to ask him more about the shooting incident. Chance was designated a minimum security inmate with no mental health concerns. After a brief stint at the state penitentiary in Walla Walla, he caught a break: he was put on work release and went to work at a Denny’s restaurant in Yakima. One day in the spring of 2014, the Lunns drove down to visit him. Before they left, they posed for a photo with him in his Denny’s uniform.

“That was the last time we seen him. He was so happy to see us,” Jackie says.

Chance got good reports from his boss, but work release has a lot of rules and he didn’t follow them all. Then his hours were cut at Denny’s. Chance changed jobs. But soon he was fired from his new job for substandard work. It was enough to get him kicked out of work release. He was sent to county jail and then to Airway Heights to serve out the last two months of his sentence.

Once there he set up a prison email account and began writing Erica. They were planning to move in together when he got out and eventually get married.

“I don’t want to lose you and you know that. I don’t have much to say ‘cause you haven’t talked to me in a while so let me know what’s up. Alright I love you and miss you.”

“What are the plans with us when I get out? It’s hard not being with you and it’s stressful. I love you and I miss you.”

“You’re my everything too, always and forever. Love, Chance. A.K.A. your sweetie.”

But over time, the tone of Chance’s emails changed. He wrote to say that he was going to get a job in a different town when he got out. He urged her to get a place on her own and to not always think of him first. Marriage would have to wait. His last message to her came August 6, 2014—12 days before his suicide.

“I know we worked too hard together to be here and then give it up like that. I don’t like it, but let me know. These are my thoughts and feelings.”

A few days later, Chance got in a fight with another inmate and had to get stitches for a busted lip. He lied to prison staff and said it was a basketball injury. He was put in segregation as punishment. Three days later he was dead.

“I don’t think that he should have been in solitary confinement,” Jackie says. “I don’t think he should have been able to hang himself.”

Erica agrees. “He shouldn’t have been alone with his thoughts,” she says.

After Chance died, Erica got a tattoo of a heart with the words “forever his.” It matches a tattoo Chance had on his chest that read “forever hers.”

Almost two years after Chance’s death, in the kitchen of their two-story farmhouse, Jackie and Charlie Lunn unfold a large yellow and white quilt with a blue border. At the top there’s an inscription in capital letters:

“You are our hero. Honoring the gift of life through organ and tissue donations.”

Before Chance was taken off of life support, his organs helped save three lives.

Chance’s was the third completed suicide in four months at Airway Heights.

At the time, Maggie Miller-Stout was the prison superintendent. In 40 years on the job, Miller-Stout says three suicides in four months at one facility was virtually unheard of.

“It was sobering,” says Miller-Stout who’s now retired. “It was, ‘holy s—, what’s next? How did we miss it? We’re good at preventing this sort of thing. How did this happen?'”

It wasn’t supposed to happen, especially at a prison like Airway Heights, which is a modern facility designed for direct supervision. In the non-segregation units staff spend their days amongst the inmates, they get to know them, and know when something is wrong. Miller-Stout says the suicides shook her staff’s confidence in their ability to recognize an inmate in trouble—to intervene before a suicide. The men who had died weren’t even on the radar of the prison’s mental health staff.

The prison’s chief psychologist, Lou Sowers, calls it a “profoundly sad” time.

“I’m scared, I’m wondering if we have a contagion issue,” Sowers recalls. Suicide contagion is a recognized phenomenon in which one suicide inspires another person to take their own life.

Miller-Stout and Sowers put their heads together and identified three categories of inmates they felt deserved more attention: recent arrivals to the prison, young inmates and inmates new to segregation. In other words inmates like Chance Kidder.

In the Washington prison system, it’s not uncommon for inmates to be transferred between facilities during their term of incarceration. Every time an inmate arrives at a new prison they’re asked a set of questions about their physical health and their mental health—and specifically about suicide.

When Chance arrived at Airway Heights he denied past suicidal feelings or attempts. His official prison record listed his self-inflicted gunshot wound, but that didn’t trigger follow up questions.

“We came to realize there was a lot of information about this young man’s history that never made it into his written files,” Miller-Stout says. “The fact that that information existed but wasn’t available was real frustrating.”

Had more information been available about Chance’s gunshot wound and other events of his life, Miller-Stout says he would have gotten more attention when he arrived at Airway Heights.

As senior staff at Airway Heights tried to figure out what was going on, the suicides were taking a toll on frontline workers.

Officer Zoltan Cziglenyi has worked at Airway Heights for more than 20 years. He was one of the first officers to respond the day inmate Tony Willoughby hanged himself in April 2014. Cziglenyi says when he got to the cell two other officers had already cut Willoughby down.

“He had a knot around the bed and then he also had one around his neck,” Cziglenyi says. “They were in the process of lowering him down to the ground. The noose was still around his neck.”

Cziglenyi says they called for a special kind of tool that’s kept in each of the prison’s living units just for this situation: a fish-hook shaped knife with serrated teeth. They’re specifically designed to cut through sheets or other materials an inmate might use to hang themselves. There are nine of these “hook knives” at Airway Heights. When the knife arrived, it was handed to Cziglenyi. He says the sheet was tied so tightly around Willoughby’s neck that he struggled to cut it loose. Once he was able to cut the sheet, they began CPR, even though Willoughby was pale and rigor mortis had set in.

Department of Corrections policy requires that officers must begin CPR even if the inmate is clearly dead. Only a medical professional is allowed to pronounce an inmate dead.

At the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton officers had to do CPR on inmate Keith Neal who had slit his arm and bled out overnight.

In the case of Willoughby, the officers at Airway Heights traded off performing chest compressions for about 15 minutes before an ambulance crew arrived and declared the inmate dead.

Cziglenyi says afterwards he was traumatized. He called his wife who also works at the prison and told her he was going home early. They have a small farm and he did some chores and tried to get his mind off what had happened. The next day he was back at work. There was paperwork to fill out. A formal stress debriefing to sit through. Then it was back to the routine. But Cziglenyi was changed.

“There was a life that was taken in front of me and I think it always will change me,” he says.

Cziglenyi says experiencing that suicide also changed how he approaches his job.

“The way I look at [inmates now] and some baseline behaviors that I might question, I might just ask them ‘hey, how things going, how’s your day going,’ stuff like that,” Cziglenyi says.

Several staff members at Airway Heights have said the suicides in 2014 changed them; made them more tense, more alert, more attuned to subtle changes in inmate behavior. After the suicides officers started referring more inmates to mental health services, and more inmates were self-referring. The mental health staff was already taxed: there were just seven of them for 2,200 inmates. Airway Heights Superintendent James Key was the assistant superintendent of the prison at the time. He says after each suicide there was a growing sense of helplessness.

“We’re fixers,” Key says. “When you talk about the spike in the suicides, we want answers and we’re people who get answers. But none of the indicators showed anything.”

But there was something they could have fixed at Airway Heights, and didn’t—at least not right away: the steel cage that covered the fire sprinkler head in the isolation cells. It’s what Chance Kidder and Morgan Bluehorse had used to hang themselves. During the same time frame, records indicate a third inmate used the cage to attempt suicide.

The cages were installed because inmates would sometimes break the sprinkler and flood their cells. But in solving one problem, the prison had created another. It turned out the diamond-shaped holes in the expanded-steel cages were just big enough to thread a strip of sheet through.

Records obtained from the Washington Department of Corrections reveal that frontline staff had considered the cages a problem for years. But in the words of one officer, getting them replaced was “like pulling teeth.” After the death of Morgan Bluehorse in May of 2014, Maggie Miller-Stout asked her staff to research an alternative. But the cages were still in place nearly three months later when Chance Kidder hanged himself in August. It took until October of 2014 before they were finally removed.

“We wanted to replace it, but didn’t feel a tremendous sense of urgency,” Miller-Stout says. “It did reach that point, but not as soon as in hindsight I wish we had.”

The rash of suicides at Airway Heights and across the Washington Department of Corrections in 2014 and 2015 revealed gaps and shortcomings that eventually led to system-wide policy changes. But not right away.

It wasn’t until March 2015 that a sense of crisis descended on the Washington Department of Corrections.

By then eight prison inmates had died by suicide in 15 months. That’s when then-Corrections Secretary Bernie Warner picked up the phone and called Lindsay Hayes.

Hayes is with the Baltimore-based National Center on Institutions and Alternatives. He’s worked in the field of suicide prevention in jails and prisons for more than 35 years and is viewed as one of the nation’s preeminent experts on them the issue.

Hayes says over the decades there’s been a dramatic decrease in “custodial suicides.” Today suicide in prison is actually a fairly rare event—it happens more often in county jails. But Hayes says that’s created a false sense of security in many prisons.

“Because they happen infrequently, we sometimes take our foot off the gas pedal for good suicide prevention practices,” Hayes says.

In June of 2015 Hayes came to Washington armed with an eight-point checklist. He visited four prisons, including Airway Heights, and wrote a 47-page report. That report included 21 recommendations for how the Washington Department of Corrections could improve its suicide prevention program—beginning one the day an inmate arrives at prison.

In Washington almost all male prison inmates begin their term of incarceration at the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton.

WCC, as it’s known, is the intake center for the state prison system. As part of the intake process, inmates undergo a mental health screening. But when Hayes visited the Washington Corrections Center he saw something that concerned him: the inmates were being asked personal questions in a setting that wasn’t completely private.

“I always equate this problem to any of us in the free world walking into a doctor’s appointment,” Hayes says. “The nurse doesn’t come out and start asking us questions of a private and confidential nature.”

In prison, it’s questions like: have you ever been told you have a mental health diagnosis? Have you ever tried to hurt or kill yourself? Hayes says these are the right questions to ask new inmates. But he says if they’re not asked in private, inmates might not answer honestly. The Washington Department of Corrections says it’s working to figure out how to create a confidential space for these screenings.

In his report Hayes also noted, “the key to any suicide prevention program is properly trained correctional staff who…are able to demonstrate an intuitive sense regarding the inmates under their care.” Hayes wrote that two-thirds of suicide victims communicate their intent in some way, but that these warning signs can easily be missed. He said staff should know an inmate “enough to know when he’s coming back from a phone call how his body language is suggesting that it didn’t go well.”

But getting frontline staff to fulfill this role isn’t always easy. Training is critical. Even before the spike in suicides, Washington prison staff were required to take annual suicide prevention training online. After the spike, the Department switched to in-person trainings and Hayes recommended ways to beef up those classroom sessions. The Department says it’s in the process of overhauling the suicide prevention curriculum.

Hayes was also concerned with the treatment of inmates who are identified as suicidal. He saw them stripped of their clothes and put in safety smocks, isolated without their belongings and, at Airway Heights, escorted in hand and leg restraints by two officers. Hayes called this “overly restrictive and seemingly punitive.” He warned that inmates who think they’re going to be punished won’t acknowledge being suicidal. The Department of Corrections says it’s made a number of changes aimed at keeping suicidal inmates safe by the least restrictive means possible.

Housing is also an important factor in suicide prevention in prison. Four of the inmate suicides in 2014 and 2015 happened in special management housing. That’s solitary confinement, or what the prison system calls segregation. Hayes says there’s a “strong association” between inmate suicide and segregation. He estimates that while only 10 to 20 percent of prison inmates are in segregation at any given time, they represent at least 30 to 40 percent of the prison suicides—maybe more.

In recent years, the Washington Department of Corrections has reduced the use of segregation for inmates. That’s part of a national trend based on research that shows the harmful effects of solitary confinement. Even so, hundreds of inmates a year still end up in isolated cells. When they do, the department now has a policy that requires a mental health evaluation within one business day of an inmate’s placement in segregation. Mental health staff are also required to conduct rounds in segregation units once a week.

Dr. Karie Rainer, the director of mental health, says what happened in 2014 and 2015 forced the Department of Corrections to review and improve its suicide prevention program.

“I wish that crisis had not occurred,” Rainer says. “Yet I don’t know that we would have been sparked to really take a look at some of these factors had we not had that crisis.”

And while Rainer is pleased with the progress, there are ongoing challenges. For instance, the Department only has 140 mental health staffers for nearly 17,000 inmates and at any given time, 15 percent of those jobs are vacant.

“It is hard to hire and in particular it’s very difficult to get psychiatrists into our services,” says Rainer. “We don’t necessarily pay well as compared to other agencies and we’re particularly challenged there.”

After the last suicide of 2015, the Washington Department of Corrections went 12 months without any inmates taking their own lives. That respite ended in September 2016 when a mentally ill inmate at the Monroe prison hanged himself. Then in December an inmate hanged himself at Airway Heights.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call for help now. The National Suicide Prevention Hotline is a free service answered by trained staff. The number is: 1-800-273-8255.

9(MDEwMDE0NjgyMDEzNDY0NDY5NTBmNTc1Yg004))

Related Stories:

Federal funding cuts, freezes hit Palouse nonprofits

Palouse area nonprofits focused on helping with emergency food and the arts have had their funding frozen or cut.

Why affordable housing providers say they’re facing an ‘existential’ crisis

Affordable housing providers across the Northwest have been contending with rising insurance premiums — and, in some cases, getting kicked off their plans altogether.

Pacific Northwest author’s new novel captures atmosphere of the region

On a gray, early spring morning, I drove to Steilacoom, Washington, to catch the ferry to Anderson Island. I boarded alongside the line of other cars and after parking, stepped out onto the deck of the boat. The ferry pushed off from the dock and rocked a little in the Puget Sound before steadying.

I took this journey to the real Anderson Island to see from the water what inspired Northwest author Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum’s new novel, “Elita,” which was published earlier this year. Sundberg Lunstrum was inspired while sailing around the Puget Sound to write a mystery novel on an island.

Sundberg Lunstrum read excerpts of the book at a gathering at Tacoma’s Grit City Books.