Yakima Classical Music Program Inspires Students To Achieve

Listen

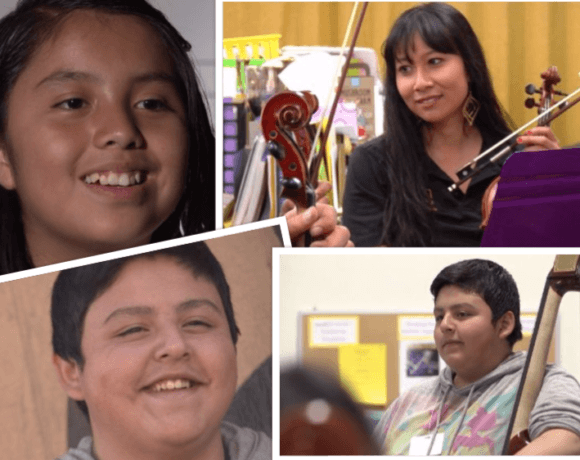

Francisco Mendoza is a seventh-grader with a sweet smile. Like many boys his age, he has yes and no answers to most questions. It wasn’t easy getting the details of his life – but maybe it’s because of the struggle and loss his family has endured. Francisco’s father died when he was three years old, and his mother works low-wage jobs to provide for her family.

But playing the cello relieves Francisco’s stress.

Francisco is one of 56 kids in YAMA, an anti-poverty, after-school program that teaches classical music in small group settings.

Seventh-grader, Francisco Mendoza says playing the cello relieves his stress and helps him do well in school.

NORTHWEST PUBLIC TELEVISION

But at one point, Francisco walked away from the program.

“I left YAMA because my friends said it was a waste of my time and guess I listened to them” he says.

Francisco often feels older than his twelve-year-old peers. “When you’re young there’s a lot that makes you happy,” Francisco says. “But when you are older you have responsibilities to worry about.”

Many kids in YAMA come from migrant families. They face poverty, home life trauma, the loss of a parent and sometimes, pressure to join gangs.

Many kids in YAMA come from migrant families. They face poverty, home life trauma, the loss of a parent and sometimes, pressure to join gangs.

According to Jose Antonin Abreu, who started El Sistema in Venezuela – the program on which YAMA is based – children who live in poverty have no public worth. But a child who learns an instrument becomes a role model for his family and peers. They develop an identity which fosters responsibility and perseverance. And that helps a child perform better in school.

Seventh-grader, Francisco Mendoza says playing the cello relieves his stress and helps him do well in school.

NORTHWEST PUBLIC TELEVISION

Perhaps Francisco wanted to feel like a carefree kid when he left YAMA, but then he noticed his grades slipping.

“My grades weren’t that good because usually I would get home and hang out with friends and forget about my homework and try to do it in the morning,” Francisco says. “But YAMA helps me pay more attention in school and reduces stress.”

“I decided to come back because there wasn’t really anything to do at my house and I really love music and missed it and all my friends are here so I came back,” Francisco says.

YAMA Director Stephanie Hsu was happy to have Francisco back, but she understood why he left.

YAMA Director, Stephanie Hsu says her program is a big commitment for young students. The program works closely with teachers and parents to monitor a child’s academic needs.

NORTHWEST PUBLIC TELELVISION

Heidi Villatoro is a sixth grader who also plays the cello. Now in her third year with YAMA, her grades show the positive effects of the program.

When I started school I had Ds and Fs but then I brought it up to As and Bs. I used to not do my homework and not pay attention in class. I had other things on my mind,” Heidi says.T”hen when I started YAMA the music was in my head and I started listening and doing my homework. Then I started getting good grades.

“When I started school I had Ds and Fs but then I brought it up to As and Bs. I used to not do my homework and not pay attention in class. I had other things on my mind,” Heidi says.T”hen when I started YAMA the music was in my head and I started listening and doing my homework. Then I started getting good grades.”

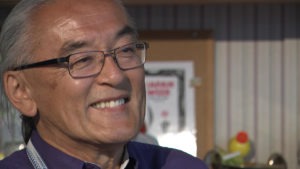

Alan Matsumoto is the principal of Garfield Elementary School where YAMA meets to practice. He noticed the parents of YAMA students being affected by their children’s performances.

Garfield Elementary School Principal, Alan Matsumoto says YAMA has strong parental support because parents see the talents of their children, not just in music, but other areas of their lives.

NORTHWEST PUBLIC TELEVISION

“I remember our first show at Seasons Hall,” Matsumoto says. “The parents were embarrassed to be down where the paying audience sits, so they all went upstairs. But the moment our kids came on, all the cell phones popped out and they’re tapping away, just like any other parent.”

Matsumoto says the program has strong family support because parents see their children’s talent and possibilities – maybe in a musical career, or going to college. One of those parents is Roxana Villatoro, Heidi’s mom.

Roxana Villatoro, Heidi’s mom, wishes her other children would join YAMA. She says the program has helped her daughter immensley both personally and in school.

NORTHWEST PUBLIC TELELVISION

“I thought that it was a program that was going to help her some. Because she was really shy,” Villatoro says. “She didn’t like to talk to people and I thought this program would give her more self-confidence. And I realized that during the time that she’s been in the program that it has helped her quite a bit.”

She didn’t like to talk to people and I thought this program would give her more self-confidence. And I realized that during the time that she’s been in the program that it has helped her quite a bit.

“It made me feel very happy because…I can’t even explain it,” Heidi says. “My mom said that if I keep doing great work in YAMA and get bigger at my instrument I could even go to Central.”

That’s Central Washington University. Heidi would be the first in her family to attend college.

“I feel proud that she has this dream and I think that she should follow her dream,” Villatoro says. “Myself, I wasn’t able to fulfill my dream so I want to support her in doing that.”

And Francisco Mendoza is thinking about his future too.

“When I grow up I want to play jazz,” Francisco says. He plans to stay on with YAMA.

“My mom thinks I can actually be like something big if I stay in music,” Francisco says. “Makes me feel good.”

Copyright 2016 Northwest Public Radio

Related Stories:

Why affordable housing providers say they’re facing an ‘existential’ crisis

Affordable housing providers across the Northwest have been contending with rising insurance premiums — and, in some cases, getting kicked off their plans altogether.

Pacific Northwest author’s new novel captures atmosphere of the region

On a gray, early spring morning, I drove to Steilacoom, Washington, to catch the ferry to Anderson Island. I boarded alongside the line of other cars and after parking, stepped out onto the deck of the boat. The ferry pushed off from the dock and rocked a little in the Puget Sound before steadying.

I took this journey to the real Anderson Island to see from the water what inspired Northwest author Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum’s new novel, “Elita,” which was published earlier this year. Sundberg Lunstrum was inspired while sailing around the Puget Sound to write a mystery novel on an island.

Sundberg Lunstrum read excerpts of the book at a gathering at Tacoma’s Grit City Books.

Repentina suspensión de Head Start afecta a cientos de niños en el centro de Washington

Suspensión de los programas Early Head Start y Head Start afecta a siete Inspire Development Centers en el centro de Washington, dejando a más de 400 niños sin apoyo educativo después de que la financiación federal nunca llegara. También provocó el despido de más de 70 personas.