Daughters Of Hanford: The Lone Woman Physicist Who Worked On Hanford’s Secret Reactor

Listen

Originally published on April 5, 2016 4:25 pm

In 1944, the U.S. pinned its hope on a secret project to win World War II. The government was counting on the B Reactor at Hanford in southeast Washington state to make enough plutonium in time. One of the physicists working against the clock was a 24-year-old woman: Leona (Woods) Marshall Libby.

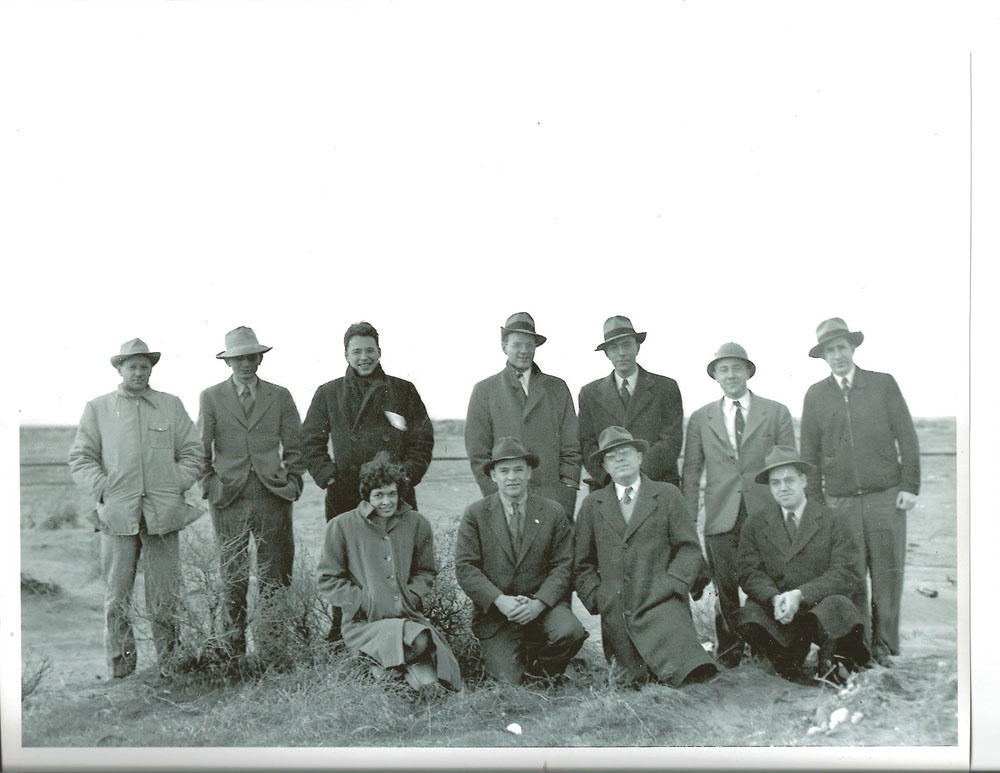

Standing from left, George Weil, Charles Wende, John Marshall, Kelly Woods, Rudolph Kanne, John Wheeler, and Sidney Kuniansky. Kneeling from left are Leona (Woods) Marshall Libby, John Miles, Hood Worthington, and Walter Jordan

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

Marshall Libby arrived in Richland with her scientist husband and their new baby. She had made sure to hide her pregnancy under baggy overalls so lab managers wouldn’t stop her work.

Her new job at Hanford was to help get the B Reactor started up to make plutonium for the atomic bomb that would later be dropped on Nagaski. The B Reactor was also the first full-scale nuclear reactor in the world. Decades later she told author Steve Sanger that to her, Richland was just a temporary post for her family.

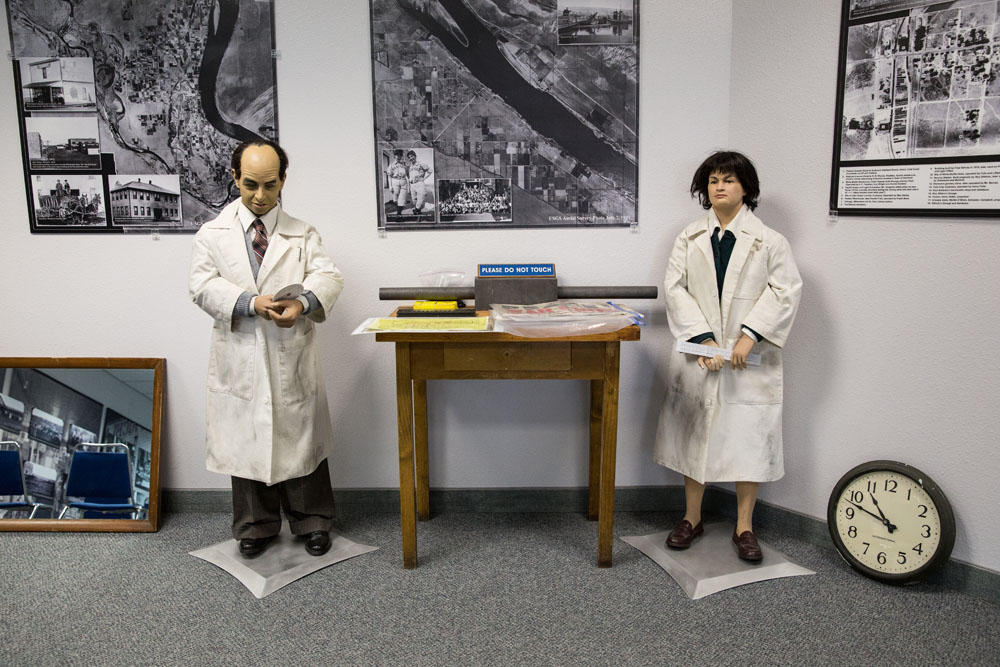

Figures representing Enrico Fermi, left, and Leona Marshall Woods Libby, stand in the waiting area of the Manhattan Project B Reactor Tour Headquarters in Richland, Wash., where visitors gather before making the nearly 40-mile drive to B Reactor.

“Well, we got out as fast as we could, but we couldn’t. We were babysitters,” Marshall Libby said.

A less-common view of B Reactor as seen from the opposite side that the tour busses arrive at.

By “babysitters” she meant she, her husband and other scientists were fixing problems and even sat the reactor in shifts all day and night.

A tour group arrives at Hanford’s B Reactor. More than 60,000 visitors have toured the B Reactor since 2009.

The birth of B Reactor

The B Reactor hissed to life on September 26, 1944. Marshall Libby was there. So were the reactor operators, supervisors, engineers and other physicists.

“Remember this was the first reactor in the world,” Marshall Libby said. “And, here were all these big shots … So here comes startup.”

They saw the cooling water heat up.

“And you could see the control rods coming out and out and out,” Marshall Libby said.

Then, after several hours, she said the reactor was dead.

“Just plain dead,” she said. “Everybody stood around and stared at everybody.”

After years of research, for the B Reactor to fail at that moment was a disaster. The scientists were racing the Germans.

After a long night, Marshall Libby got in a government car with top scientist Enrico Fermi and headed the 40 desert miles back to Richland — defeated.

Ominous signs are seen throughout B Reactor, although hazards are sealed or removed in sections open to visitors.

“It was way after midnight,” she said. “And so we drove back in the moonlight. And we argued about what caused it.”

This detail of the famous B Reactor front face shows some of the 2,004 aluminum tubes that once housed uranium slugs.

Eventually the group figured out the problem was a by-product gas called xenon. Within a few months, they overcame the xenon problem by adding more uranium fuel into the reactor core.

Since Leona Woods Marshall Libby was the only woman working at B Reactor, they had to construct a women’s bathroom especially for her. This framed informational sheet is posted outside the bathroom.

About eight months after that, the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb with Hanford plutonium on Nagasaki, Japan. Six days later, World War II ended.

There’s nothing outwardly remarkable about the bathroom constructed for Leona Woods Marshall libby, but the room stands as an unusual historical marker for the pioneer.

Since then, many have debated the ethics of using the bomb. But Marshall Libby believed to the end.

“It was a desperate time,” she said. “I think we did right and we couldn’t have done differently.”

Not just heroes — superheroes

Marshall Libby was one of a handful of women scientists on the Manhattan Project nationwide. Their stories were buried in classified documents for decades.

Pnina Abir-Am, a science historian at Brandeis University, said the stories of Marshall Libby and others were not properly studied until the women’s liberation movement — and that they’re still not fully appreciated.

“These women scientists with families were real, were superheroes, not just heroes,” Abir-Am said. “And you know we don’t know much about them.”

Marshall Libby was able to publish a book about her life and wartime work in 1979. She died at age 67, after a long illness.

Marshall Libby isn’t really famous — but she’s always had one room at the B Reactor that was just hers: The women’s bathroom. It was there just for her. Today, just near the door, hangs a small weathered picture of her girlish face.

The stories and photos in our Daughters of Hanford series are in an exhibit open now at the REACH in Richland. Find more at daughtersofhanford.org.

Audio interview of Leona (Woods) Marshall Libby courtesy of Steve Sanger and the Voices of the Manhattan Project.

Historical research assistance by David Bolingbroke, a history Ph.D. student at Washington State University.

Related Stories:

Unpacked: Giving spiritual meaning to food during Lent

For Lent this year, the Rev. Rene’ Devantier of Spokane’s Fowler United Methodist Church uses real food and drink elements. (Credit: Cody Wendt / FāVS News) Listen (Runtime 1:47) Read

United Farms Workers call for boycott of Windmill Farms products at Tacoma rally

People traveled from across Washington state to rally outside of a Tacoma Safeway store in support of farm workers Monday afternoon.

The United Farm Workers and their supporters are calling on Windmill Farms in Sunnyside to recognize the unionization efforts and give workers a contract. The union said workers have been trying to get recognition for two years.

Flatt named in 2025 WSU Tri-Cities Women of Distinction class

Courtney Flatt, Northwest Public Broadcasting’s senior environment and energy correspondent. (Credit: Washington State University Tri-Cities) Read Courtney Flatt, Northwest Public Broadcasting’s senior environment and energy correspondent, was named a Woman